By mid summer of this year, the fortunes of the long-troubled Oakland Police Department appeared to have finally changed. The city’s stubbornly high violent crime rate was down significantly, with roughly 30 percent fewer homicides and 37 percent fewer robberies than in 2013. The department also appeared to be getting closer to finally fulfilling the court-ordered reforms that stemmed from The Riders police misconduct scandal in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Independent Monitor Robert Warshaw, the former chief of police of Rochester, New York who is overseeing OPD’s reform effort, wrote in a July 29 report that the department had achieved the “highest number of tasks in compliance that we have found since the beginning of our tenure.” Warshaw also commended both Mayor Jean Quan and Police Chief Sean Whent for the department’s progress.

Squad cars parked outside of the Oakland PD Administration Building. Credits: Bert Johnson

Civil rights attorney Jim Chanin said OPD’s disciplinary process lacks credibility. Credits: Bert Johnson

OPD investigator Rachael Van Sloten, who worked on the Olsen case criminal probe, commiserated with Robert Roche on his personal Facebook page after he testified in the Olsen civil suit.

Van Sloten changed her Facebook profile to celebrate the arbitrator’s order that OPD rehire Roche. She referred to Roche as “Saint Rob.”

But in a stunning move the next day, a labor arbitrator ordered OPD to rehire Officer Robert Roche, the disgraced cop who had been fired for throwing a tear gas-filled flash-bang grenade into a crowd of Occupy Oakland demonstrators. The protesters had been coming to the aid of the wounded and prone Marine Corps veteran Scott Olsen on October 25, 2011.

In February 2012, after reviewing video recordings and other police records, private investigator Jacob Crawford and I identified Roche as the officer who threw the flash-bang grenade at Olsen (see “Officer in Scott Olsen Incident Identified?” 2/22/12). Additional reporting later revealed that OPD had prematurely ended its investigation into the Olsen incident and that the department investigators lied to the Alameda District Attorney’s Office about it (see, “OPD Screws Up Scott Olsen Investigation,” 6/13/12). OPD’s conduct elicited concern from former Baltimore Police Commissioner Tom Frazier, whom the city had hired to review OPD’s conduct during Occupy Oakland. Frazier determined that department investigators had “compromised” the probe of the Olsen incident.

The arbitrator’s order to rehire Roche, which came less than four months after Oakland had reached a $4.5 million legal settlement with Olsen, frustrated federal Judge Thelton Judge Henderson, who oversees Warshaw and OPD’s compliance with the court-mandated reforms. On August 14, Henderson issued an order describing his dissatisfaction with the rehiring of Roche and OPD’s disciplinary process. “This is not the first time an arbitrator has overturned an officer’s termination by [OPD and the City of Oakland], and, indeed, this Court previously ordered the parties to discuss the reinstatement of Officer Hector Jimenez by arbitration,” Henderson wrote. “The City’s promises to correct deficiencies at that time have fallen short, and further intervention by this Court is now required.”

Henderson then gave Warshaw sweeping authority to investigate OPD’s process for investigating and disciplining officers, and to determine why the department and the city’s decisions to fire problem cops have been repeatedly overturned by arbitrators. The judge also directed Warshaw to examine how the city selects expert witnesses and how the city attorney assigns lawyers for arbitration hearings, and whether those lawyers are adequately prepared. Warshaw will also determine whether the process for selecting arbitrators should be changed.

The city and OPD’s inability to discipline and terminate problem officers has long frustrated civil rights advocates. “There’s no credibility to the discipline process if they can’t make it stick, particularly in the most serious cases,” said attorney Jim Chanin, who brought the original civil suit against The Riders with his colleague John Burris.

OPD’s flawed disciplinary process also represents a major roadblock for Oakland in its ongoing effort to extract the department from the federal court’s costly oversight regime. The ordered rehiring of Roche also was a significant setback at a time when OPD appeared to be making strides in living up to the court-ordered reforms, also known as the Negotiated Settlement Agreement (NSA). “Just like any failure to impose appropriate discipline by the [police] Chief or City Administrator, any reversal of appropriate discipline at arbitration undermines the very objectives of the NSA,” Henderson wrote.

It’s unclear when Warshaw will complete his examination of OPD’s disciplinary process and issue recommendations for correcting its flaws. However, the details of the Roche case reveal that OPD’s attempts to discipline him may have been undermined by the personal bias of an OPD investigator who worked on the criminal probe of the Olsen incident. Furthermore, the case brings up serious questions about how the Oakland City Attorney’s office has handled arbitration cases and whether arbitration itself is a proper forum for meting out meaningful discipline to police officers.

Samuel Walker, a professor emeritus of criminal justice at the University of Nebraska-Omaha who is one of the nation’s foremost experts on police oversight, said the forced rehiring of officers such as Roche and Jimenez also represented a major setback for the city’s police-community relations. “The rehiring of these officers has a devastating impact on public opinion in the community, which is likely to now see the whole process as a charade.”

Before October 25, 2011, Officer Robert Roche was a member of OPD’s guns and gangs taskforce, and had qualified both as an acting sergeant and as a patrol rifleman who was authorized to use an AR-15 semiautomatic rifle while on duty. He also had been involved in three fatal shootings: the 2006 killing of teenager Ronald Brazier, who allegedly fired on Roche and two other officers; the 2007 death of unarmed Jeremiah Dye, who Roche shot and killed in a crawlspace underneath an East Oakland house after Dye had fled from a traffic stop at which an OPD officer was shot; and the 2008 fatal shooting of teenager Jose Buenrostro, who was in possession of a sawed-off rifle but allegedly had his hands in the air when he was shot by Roche and other members of the gang task force. The Alameda District Attorney’s Office cleared Roche of criminal wrongdoing in all three shootings. But the City of Oakland paid $500,000 to Buenrostro’s family in a wrongful-death settlement.

On the evening October 25, 2011, Roche was a member of one of the two “Tango Teams” assigned to hold Frank Ogawa Plaza and repel Occupy Oakland protesters whom police had ousted from their encampment in front of City Hall early that morning. Around 7:45 p.m. that day, on the orders of then-Captain Paul Figueroa, the two Tango Teams unleashed several volleys of tear gas, flash-bang grenades, and less-than-lethal projectiles onto a crowd of more than one thousand protesters at 14th Street and Broadway. Olsen, who was standing with his Veterans for Peace colleague Joshua Shepard about ten feet from the police barricade on 14th, was turning to flee as he was shot in the left side of his head by a less-than-lethal projectile that a subsequent investigation determined was fired by an Oakland police officer. OPD’s Tango Teams had been ordered to fire less-than-lethal rounds at anyone who threw tear gas canisters back at police — although Olsen had never done so.

As Olsen lay on the ground in front of the police line, a crowd of demonstrators rushed to his aid. At the time, Roche was standing at the line training his shotgun back and forth across the crowd. Video of the incident showed the acting sergeant step back from the line, lower his gun, and toss a tear-gas-filled flash-bang grenade into the crowd. The grenade exploded near Olsen’s body.

After an independent review of OPD’s conduct during Occupy Oakland found the department’s criminal investigators — namely, Jim Rullamas — had prematurely closed the criminal probe of the Olsen shooting, the city appointed an independent investigator to review the case. The department sent a termination letter to Roche in the fall of 2012.

According to sources, Roche was initially terminated for lying to investigators about his actions during the demonstration, for tossing the flash-bang onto Olsen and his rescuers, and for allegedly firing the projectile that wounded Olsen (however, a subsequent police investigation indicated that another officer was likely responsible for wounding Olsen). During a department disciplinary proceeding known as a Skelly hearing, after Roche had received his termination letter, it was determined that there was insufficient evidence to sustain the findings that Roche had lied to investigators and had shot Olsen with a beanbag. However, Police Chief Whent decided to fire Roche for tossing the tear-gas-filled flash-bang grenade.

On July 30 of this year, labor arbitrator David Stiteler overturned the termination of Roche on the grounds that Roche had been ordered to toss the tear gas at Olsen by Figueroa, who was in charge of the operation (Figueroa is now an assistant chief). Roche’s attorney, Justin Buffington, also said Stiteler concluded that Roche was telling the truth when he said he was unaware that Olsen was lying prostrate and injured on the ground fifteen feet away, in his direct line of sight.

Many OPD officers viewed Stiteler’s ruling as vindication of their long-held belief that rank-and-file cops are unfairly punished, while command staffers manage to escape discipline. “Roche is a phenomenal police officer, and he was scapegoated like all the other officers from the Occupy experience,” said Sergeant Barry Donelan, the president of the Oakland Police Officers’ Association, to the Oakland Tribune. (Donelan did not respond to interview requests for this report.)

A review of social media activity involving OPD officers also reveals that some of them maintained close friendships with Robert Roche. And among his friends was a criminal investigator assigned to look into the Olsen incident. In one Facebook post after the arbitrator’s ruling, that officer — Sergeant Rachael Van Sloten — changed her profile picture to a photo collage titled “Well Deserved Victory.” The collage included a picture of Saint Patrick, an Irish Catholic saint, with an image of Roche’s face superimposed over Patrick’s, and Patrick’s name replaced with “Rob.” The saint is dressed in robes embroidered with crucifixes. The collage also included a photo of police officers, including some of Roche’s Tango Team buddies, having a celebratory drink at the Warehouse, a longtime cop bar in the city’s Jack London district.

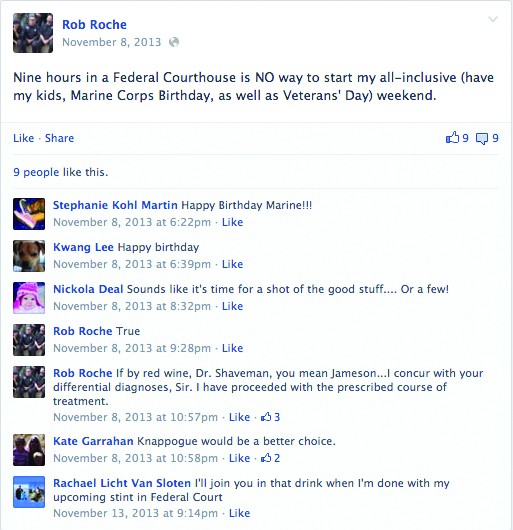

Van Sloten posted often on Roche’s Facebook page. In one post from November 2013, after Roche had been fired, Roche lamented about the long day he had spent at the federal courthouse testifying in the Olsen civil case. Roche noted in comments on the post that he was drinking a shot of Jameson’s Irish whiskey after court. Van Sloten then commented, “I’ll join you in that drink when I’m done with my upcoming stint in Federal Court.” (It’s not clear whether Van Sloten was testifying in the same case.)

Van Sloten’s relationship with Roche and her Facebook celebration after the arbitrator’s ruling in his favor raises serious questions about the neutrality of not only the police investigation of the Olsen incident, but of all OPD investigations involving police officer misconduct.

Van Sloten did not respond to requests for comment. In a statement, Whent promised to investigate Van Sloten’s relationship with Roche. “We currently have a process in place to prevent officers from investigating cases involving individuals with whom they have a personal relationship,” Whent wrote.

According to public records, Roche earned $151,343 in total salary in 2013. He was reinstated with two years of back pay totaling more than $300,000. When that number is added to the legal settlements Oakland has paid out for the Olsen and Buenrostro cases, Roche has cost the city at least $5.3 million for his actions.

The Oakland City Attorney’s Office handling of the Roche arbitration case also raises numerous questions. Before Roche’s arbitration hearing began on April 7, Oakland City Attorney Barbara Parker assigned a new attorney, Stephen Roberts of the Nossaman LLP firm in San Francisco, to defend Whent’s decision to fire Roche. By contrast, Roche’s attorney, Justin Buffington, who works for the law firm of Rains Lucia Stern, had represented his client since 2012.

In an interview, Olsen questioned Parker’s decision to switch attorneys at the last minute, and believes it likely played a role in the arbitrator’s ruling in Roche’s favor. “Roche lies to the investigators and threw a stun grenade at someone in need of medical attention. How do you lose that case?” Olsen said.

Parker’s decision-making also raised eyebrows among observers of OPD’s disciplinary process. “Are the city attorneys capable of defending the city in use of force cases?” asked Professor Walker. “It’s a matter of legal competency, and it appears that the police union has better, more experienced counsel.”

Statistics produced by Parker’s office show that the city has prevailed in just three of fifteen police arbitration cases since 2012. In seven cases, the city lost outright, with the officer’s punishment being completely overturned (like it was in the Roche case). In five other cases, the arbitrator reduced the severity of the punishment.

But the Oakland Police Officers’ Association (OPOA), the city’s police union, contends that Parker’s tallies are not correct. At an August 16 protest in West Oakland, Sergeant Jake Bassett, the vice president of OPOA, said the city had lost sixteen of out the last sixteen cases that went to arbitration. Determining who is right is difficult because arbitration cases are secret, and the decisions are released only if the officer in question chooses to do so. Even Stiteler’s written order explaining the decision to mandate the rehiring of Roche is not publicly available.

As a result, it’s hard to assess the performance and competence of lawyers hired by the City Attorney’s Office in police arbitration cases. However, at least one other arbitration case provides insight into the city’s handling of such cases and raises red flags not only about the attorneys involved, but also about police internal affairs investigations.

In March 2011, arbitrator David Gaba ordered the reinstatement of Officer Hector Jimenez. OPD had fired Jimenez two years earlier after he had killed two men — Andrew Moppin-Buckskin and Jody “Mack” Woodfox — in separate shootings within seven months of each other in 2008. Jimenez was a rookie officer at the time and had not cleared his one-year probationary period. Jimenez fatally shot Moppin-Buckskin on January 1, 2008, and then shot Woodfox in the back while Woodfox was fleeing from a traffic stop in July 2008.

OPD terminated Jimenez in July 2009 after a department investigation concluded that the officer had violated policy by firing on an unarmed, fleeing man who presented no threat. But arbitrator Gaba ruled that Jimenez had acted under a department policy that stated that officers “should consider any high-risk suspect to be armed until they have personally assured themselves otherwise.” Like Roche, Jimenez was represented by Justin Buffington in his arbitration case. Jimenez received more than $200,000 in back pay from the city.

In the summer of 2011, attorneys John Burris and Jim Chanin presented Judge Henderson with the results of an independent investigation they had conducted into the 2008 Woodfox shooting. Burris, who represented Woodfox’s family in a wrongful death suit that resulted in a $650,000 settlement paid by the city, had hired a private investigator who located two witnesses to the shooting who hadn’t been interviewed by OPD. Both witnesses confirmed that Woodfox had been fleeing and had his back to Jimenez when Jimenez shot and killed him.

“We found new witnesses to the Woodfox shooting, but the city refused to go out and interview them,” Burris said. Chanin said the police department and the city’s refusal to use the two witnesses seriously undermined Jimenez’s termination once it reached arbitration.

Oakland cops, meanwhile, frequently point to another police disciplinary case — that of Officer Bryan Franks — as evidence that the City Attorney’s Office mishandles its responsibilities. On September 25, 2011, Franks chased Arthur Raleigh down the 9900 block of Cherry Avenue in East Oakland after Raleigh ran from a car stop. Franks tackled Raleigh, who tumbled to the ground and dropped a revolver he was holding in his hand. According to Franks, Raleigh picked up the revolver and turned toward Franks while pointing the weapon. Franks fired his own gun, killing Raleigh.

Following an internal affairs investigation into the shooting, then-police chief Howard Jordan terminated Franks in April 2012. However, Franks’ attorney Michael Rains (the lead partner in the firm that employs Buffington) uncovered an expert analysis of video footage from Franks’ chest-mounted camera that had been withheld from Franks and OPD investigators by the Oakland City Attorney’s Office. The analysis supported Franks’ version of the facts. In July 2012, after the report surfaced, Jordan reversed his decision and rescinded Franks’ termination letter.

Rains later filed an official misconduct complaint with the State Bar of California against Rocio Fierro of the Oakland City Attorney’s Office over the incident. However, no discipline resulted from the complaint.

In an interview, Parker said that her office is working closely with the city administrator and the police department to cooperate with Warshaw’s probe of OPD’s disciplinary process. Parker said the Jimenez case occurred while her predecessor John Russo was still in office. With regard to the Roche case, Parker disagreed with criticisms about her decision to change lawyers just before the arbitration hearing. “The timing of the assignment of that case wasn’t a factor,” Parker said, adding that the loss of nineteen members of City Attorney’s Office during the past decade due to budget cuts has diminished her office’s institutional knowledge and hindered its ability to handle cases.

Some observers of OPD say the OPOA’s collective bargaining agreement, which gives the police union the power to choose arbitrators for each case, is also a major roadblock to disciplining officers. “That’s not going away: Collective bargaining agreements are pretty standard now for police contracts,” Burris said, noting that civil rights attorneys in other cities have commiserated with him about law enforcement’s ability to select labor arbitrators and the resulting difficulty in upholding discipline and terminations.

“At the end of the day, it is about the arbitrators themselves, who appear reluctant to take a job away from a police officer and appear to have a pro-police bias,” Burris said. “The question is whether the city presents sufficient evidence to overcome that bias.”

Professor Walker of the University of Nebraska-Omaha contends that arbitration is a flawed system for dealing with problem officers. “Arbitrators like to split the baby both ways, and giving both parties something means that the cops get their job back,” Walker said. “It is an inherently flawed way to deal with police terminations.”

In addition to undermining community trust in police departments, the required rehiring of problem officers with documented histories of misconduct and improper use of force also is damaging to the internal culture of a police department, Walker said. Reinstating problem officers, he said, “bolsters the morale of the worst officers and undermines the morale of the good officers because they’re known to be bad officers by others in the department.”

In January, the Express published the results of an internal survey of OPD officers that corroborated Walker’s assertion. According to the survey, some officers said OPD “is divided between a group of people trying to move the police department forward into a progressive and modern police force and those holding on to old times, old ways, and a good old boys club.”

Correction: The original version of this story misstated when the exculpatory evidence had been withheld from Officer Franks’ attorneys. It was when the case was still in its disciplinary stage and not yet had reached arbitration. Also, the story misstated the month in which the City of Oakland hired an attorney in the Roche arbitration case. It was February, not March.