Mathieu Amalric must be the busiest actor in the world. It seems as if he’s in every third movie being released these days, including a stint as the new James Bond villain in Quantum of Solace. And let’s not forget his sparkling character work in The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, Munich, and A Secret. On second thought, scratch that last title — the film sank despite his efforts.

With his impish facial features and playful wit, the half-Polish Amalric (according to IMDB.com he was born in the village where Roman Polanski once lived) is certainly one of the French film industry’s leading exports, adept at providing a lift when a scenario begins to lag, simply by sauntering onscreen. In Arnaud Desplechin’s family drama A Christmas Tale (Un conte de Noël), Amalric lights up the screen in the role of Henri, the putative black sheep of the large and very miserable Vuillard family as it gathers together for the holidays in the city of Roubaix in the North of France. The screen could use some lighting up.

Henri is the messiest, most wounded, and most interesting of the grown offspring of Junon (Catherine Deneuve, radiantly bitchy) and Abel (Jean-Paul Roussillon), whose idea of a good time is inviting the kids over, consuming vats of wine, and then pointing out their weaknesses in front of the assembled until someone explodes. You guessed it, what we’ve got here is yet another dysfunctional family drama. Everyone in the Vuillard extended clan is either physically ill or neurotic, or both. Someone is always getting his or her blood work done. Maladies du sang are the order of the day, as are never-ending recriminations about the long-ago death by leukemia of Henri’s younger brother Joseph, at age six. Cancer stalks these characters like some sort of family curse.

Matriarch Junon is the Grand Inquisitor, and everyone takes his or her turn on the rack, notably youngest sibling Ivan (Melvil Poupaud), his wife Sylvia (Chiara Mastroianni), and cousin Simon the artist (Laurent Capelluto), the real black sheep of the Vuillards, who at least has the sense to get laid on Christmas — it’s the most effective antidote. Henri’s girlfriend Faunia (Emmanuelle Devos) doesn’t exactly know what to make of this nest of ninnies. She’s as alternately repelled and fascinated as we are, but mostly repelled, just like us. There’s a Christmas play put on by the grandchildren, an awful Christmas Eve dinner, and a few welcome distractions from the general mood of funk.

As dreary as Desplechin and Emmanuel Bourdieu’s scenario is, the director takes pity on the viewers by contriving a few diversions, such as the turntablist concert in the town and the antics of the two little boys, Baptiste and Bastien. Nicolas Cantin’s sound engineering deserves special mention, in concert with a subtly evocative needle-drop music track that utilizes Gershwin’s “Lullaby,” Cecil Taylor, Charles Mingus, and Indian classical music to provide a bit of emotional shading for these poor devils.

In the end, even Amalric’s ray of light can’t penetrate the gloom enough to make A Christmas Tale much more than a rather strained actors’ exercise. Henri ends up providing a bone marrow transplant for Junon, but that’s no guarantee of happiness in itself. Not in this family. His parting message to his mother: “I’m rejecting everything from you.” Director/co-writer Desplechin, who also directed Amalric, Deneuve, and Devos in the fitfully entertaining Kings and Queen (2004), evidently has an interest in illness as metaphor. It doesn’t quite translate.

Director Robert Aldrich depicted his share of troubled families, too, but they were more likely to settle matters with a six-gun, or perhaps a baked rat served up in a covered dish.

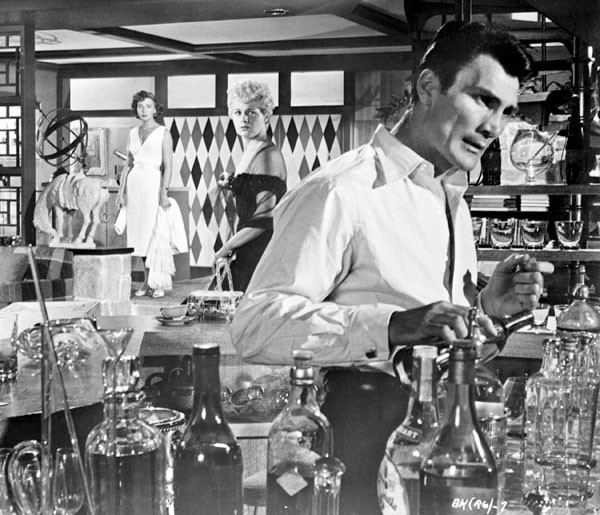

The term “Hollywood maverick” is sorely overused, but Aldrich (1918-1983) richly deserved the title. In his forty-year, 67-film career as a feature filmmaker, Aldrich mostly specialized in rugged, he-man action yarns in which marginalized outsiders persevere against a corrupt system, whether it’s on the grisly Western frontier (Ulzana’s Raid, Apache), aboard a freight train in the Great Depression (Emperor of the North Pole), in the European battlefields of WWII (The Dirty Dozen), on a penitentiary football field (The Longest Yard), or in frantic, atomic-age Los Angeles (Kiss Me Deadly), where a blazingly blunt private eye goes completely nuclear. He leavened those testosterone heroics with a short but well chosen roster of perverse anti-“women’s” pictures — What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?; Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte; Autumn Leaves — in which strong female protagonists like Bette Davis and Joan Crawford act out the same sort of angst-laden struggles against fate as Burt Lancaster or Lee Marvin. And then there’s The Killing of Sister George, a British-made 1968 lesbian relationship drama, given an ‘X’ rating for its candid love scenes.

For the mini-retrospective “A Dirty Dozen: The Films of Aldrich,” Pacific Film Archive curator Steve Seid plays the field with a succinct but typically near-hysterical playlist of representative Aldriches, including some rarities. The series is enlivened by personal appearances by filmmaker Adell Aldrich, daughter of the late director (November 21, December 13), and film historian David Thomson (December 6).

It opens Friday evening, November 21, with the Gary Cooper-Lancaster oater Vera Cruz (6:30) plus an overlooked Aldrich gem, 1961’s The Last Sunset (8:45). In the latter, Texas sheriff Rock Hudson pursues outlaw Kirk Douglas to Mexico, where they both join a cattle drive with lily-livered gringo rancher Joseph Cotten, his voluptuous wife Dorothy Malone, and their appealingly virginal daughter Carol Lynley, who develops a crush on the Douglas character, incidentally her mom’s long-lost beau. Forget about Freudian Westerns — this one owes more to Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, the Austrian writer from whose name we get the word masochism. Dalton Trumbo adapted the screenplay. It’s unclear whether he created the scene in which the maniacal O’Malley (Douglas) grabs a dog in a strangle hold.

Also in the retrospective are a pair of non-cowboy Aldrich stress-fests: the 1977 political thriller Twilight’s Last Gleaming, with Lancaster as a demented former Vietnam war POW (does this sound familiar?) threatening national security; and Clifford Odets’ Tinseltown nail-biter The Big Knife, with Jack Palance as a freaked-out movie star surrounded by Ida Lupino, Shelley Winters, and Rod Steiger — that’s enough to frighten anyone. Aldrich’s last film, the nutty female-wrestling comedy …All the Marbles, puts a fitting capper on things, as manager Peter Falk shepherds his prize combatants, the California Dolls (buxotic Vicki Frederick and Laurene Landon), all the way from Great Lakes tank towns to the championship match in Reno. Male or female, Aldrich’s characters were invariably boldly drawn and larger than life.