One of Mike Nicholls’ all-time favorite publications is Emigre, a Bay Area graphic design magazine that ceased printing in 2005. A self-described magazine geek, Nicholls loved the fonts as much as the immigrant voices in Emigre, and he never found comparable conversations in another outlet after that.

In 2006, living in Philadelphia, Nicholls came up with the idea for Umber. He envisioned it as a printed magazine for designers and other creatives, told from the perspective of people of color.

Nicholls always adored magazines. PORT Magazine, Juxtapoz Magazine, and Belle Sf are some of his other favorites, although he grew up snatching his mom’s copies of ELLE Magazine. At an early age, he showed a talent for illustration. He’d draw the models from ELLE, only he’d reimagine them as Black women. Lack of representation has long been on his mind.

Over the years, Nicholls kept thinking someone would put out a magazine like Umber. He wanted to find a publication that truly spoke to him — something that showcased creative nuance and people of color while also not explicitly drawing attention to their backgrounds. He wanted to read about Black designers like him — not because they were Black, but because they were great designers. High art and design magazines that he otherwise admired rarely seemed to feature people of color.

“I felt like this particular kind [of magazine] I wanted wasn’t there yet,” Nicholls said. “I waited, waited, waited. Nobody does it.”

He moved to Oakland in 2008. A creative director by trade, he even went as far as mocking up a prototype for Umber five years ago. But with a full-time job and a young son, he never got around to pursuing it further. Then, Donald Trump won the presidential election. “If I’m gonna do something, this is the time to do it,” Nicholls said.

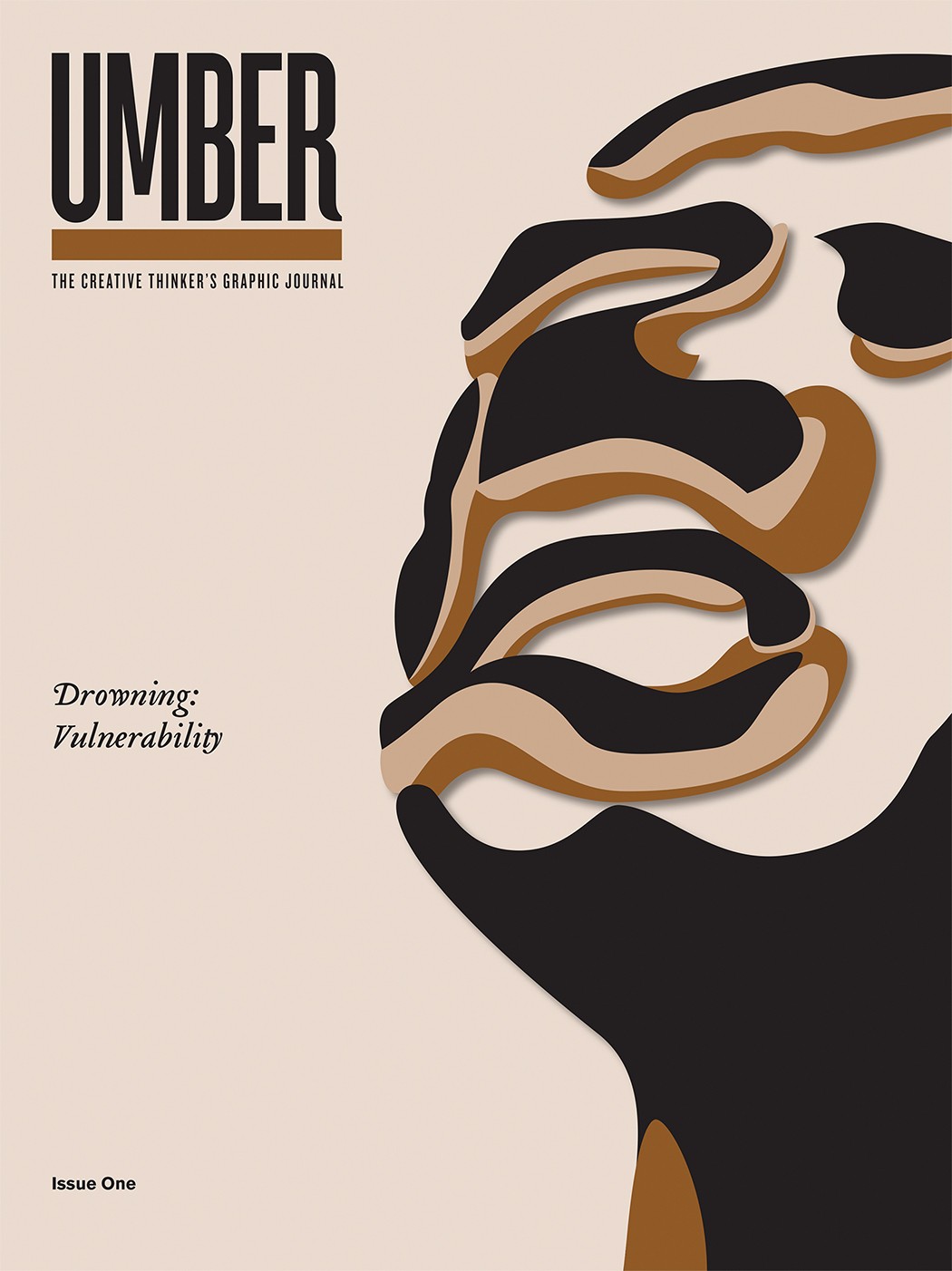

More than 10 years in the making, the first issue of Umber was finally released this fall. The name refers to a brownish hue, and the entire magazine is printed exclusively in black and brown ink as a nod to its writers and concept. The biannual magazine is 50 pages long and printed on quality paper with a matte finish via Solstice Press in Oakland.

The concept, design, illustrations, editing, and some writing was all done by Nicholls. Even though it’s full of other voices, Umber is very much a personal work. The cover is a bold, graphic version of one of his dad’s paintings, one that Nicholls has kept since his father first gave it to him at age 2. It traveled from New York, where Nicholls was born, to North Carolina, Georgia, Illinois, Pennsylvania, and finally to California. His father wasn’t really around when Nicholls was growing up — he stayed in New York, an artist-turned-minister who has recently come back into Nicholls’ life.

When he started planning the content for Umber, Nicholls quickly realized his dad needed to be the featured artist, that the painting he held onto for so long needed to be its cover art, so that he could move forward. He has spent his whole life comparing himself to his father — they’re both artists and even have the same full name — and, thanks to Umber, Nicholls finally feels like that’s behind him.

“I realized our stories are similar. He didn’t grow up with his dad. I didn’t grow up with him,” he said. “What better way to be vulnerable and give up yourself than talk about the relationship between you and your dad, and lack thereof?”

Nicholls asked his dad to contribute a written piece that explicitly discusses their rocky history. It felt appropriate. Nicholls wanted the entire first issue to explore vulnerability as a way for artists to grow.

“As an artist, you’re always vulnerable,” he said. “You want to let people know you do art but you don’t want to be criticized or judged, so you just keep it to yourself. … Even the whole process of making Umber was vulnerable because I was doing everything for the first time.”

Even though Nicholls has contributed to magazines such as Playboy and Jazz Times, the process of creating, fundraising for, and selling a new publication has been a different challenge. He successfully raised more than $10,000 through a Kickstarter campaign this summer, and now his virtually ad-free magazine can be found in bookstores and museums as far away as the United Kingdom. In Oakland, it’s available at Issues Shop, East Bay Booksellers, Owl N Wood, and the Oakland Museum of California’s gift shop.

Eventually, Nicholls hopes Umber can become his full-time gig. He realizes he’ll need to sell more advertisements for the second issue, which he hopes to release in the spring, but he won’t sacrifice his design aesthetics for them. Like the magazines Monocle and Lucky Peach, ads will need to look like seamless parts of Umber. He’s also imagining online content and videos — any growth that happens organically is good, he said. But there will never be Umber without the print magazine. Nicholls is wholly dedicated to the medium, and always with a matte finish.

“I want you to feel the tooth of the paper, like skin,” he said. “To experience Umber is to hold it in your hands.”