For one hour, between lunch and dinner service, Shan Dong (328 10th St., Ste. 101, Oakland) closes and employees sit for a staff meal. On this particular afternoon at the popular Chinatown eatery, manager and owner Charles Hung is wrapping up a plate of beef and noodles — the thick, handmade sort that keep customers coming — and reminiscing on how he came to take over his parents’ restaurant.

Six months after Helen and Brang Hung opened Shan Dong in 1991, they reached out to their son for help. At the time, Charles was 21 and studying business administration at San Francisco City College.

“They asked me, ‘You want to come back and help a little bit?’ And I said, ‘Okay, why not?’ I’ve been stuck here ever since.”

It’s an interesting choice of words for a man who has successfully run a business in an especially unforgiving industry for more than two decades. But as it turns out, succeeding your parents’ food business isn’t always organic or by choice. Many enter that work driven by the guilt of leaving their parents to handle the daily labor that restaurants require. Once inside the arduous cycle of long days and late nights, a resentment can creep in for restaurateurs who sacrifice any semblance of a balanced life to continue the family business.

“Am I happy? I don’t know,” Charles said. “After 26 years I’d like to think that we’re doing a good job, but am I happy with a personal life? Not really.”

The Hungs immigrated to San Francisco from Taiwan in 1982. Brang, who worked in real estate in Taiwan, took a dishwashing position upon moving to the Bay Area while Helen nannied to support the family. A decade later, the family made their way to Oakland’s Chinatown and soon opened Shan Dong, where Brang cooked in the style of his home province, Shandong, in northern China.

Five years later, Charles took on a bigger role than waiting tables and cleaning when his parents visited Taiwan.

“That’s when I took over the books. And when I took over the books, I was in total shock,” he remembered. “I realized how much debt that we were in.”

And though he had already dropped out of college to be at the restaurant full-time, that realization marked when Charles truly took over the business.

Over the next seven years, he worked diligently to clear that debt, prioritizing high-interest credit cards and mending the financial trust with the restaurant’s suppliers.

Three years ago, Brang passed away just shy of 80 years old. Helen is still working at the restaurant, but Charles would like her to stop and only visit the restaurant to eat. With his own two teenaged children, Charles is much more protective.

“I told them, ‘I don’t want you to go into the restaurant business unless you choose to. But I wouldn’t ask you to come to the restaurant and help,'” he said. His kids have never worked at Shan Dong. “I didn’t have any choice. For us, it was about surviving.”

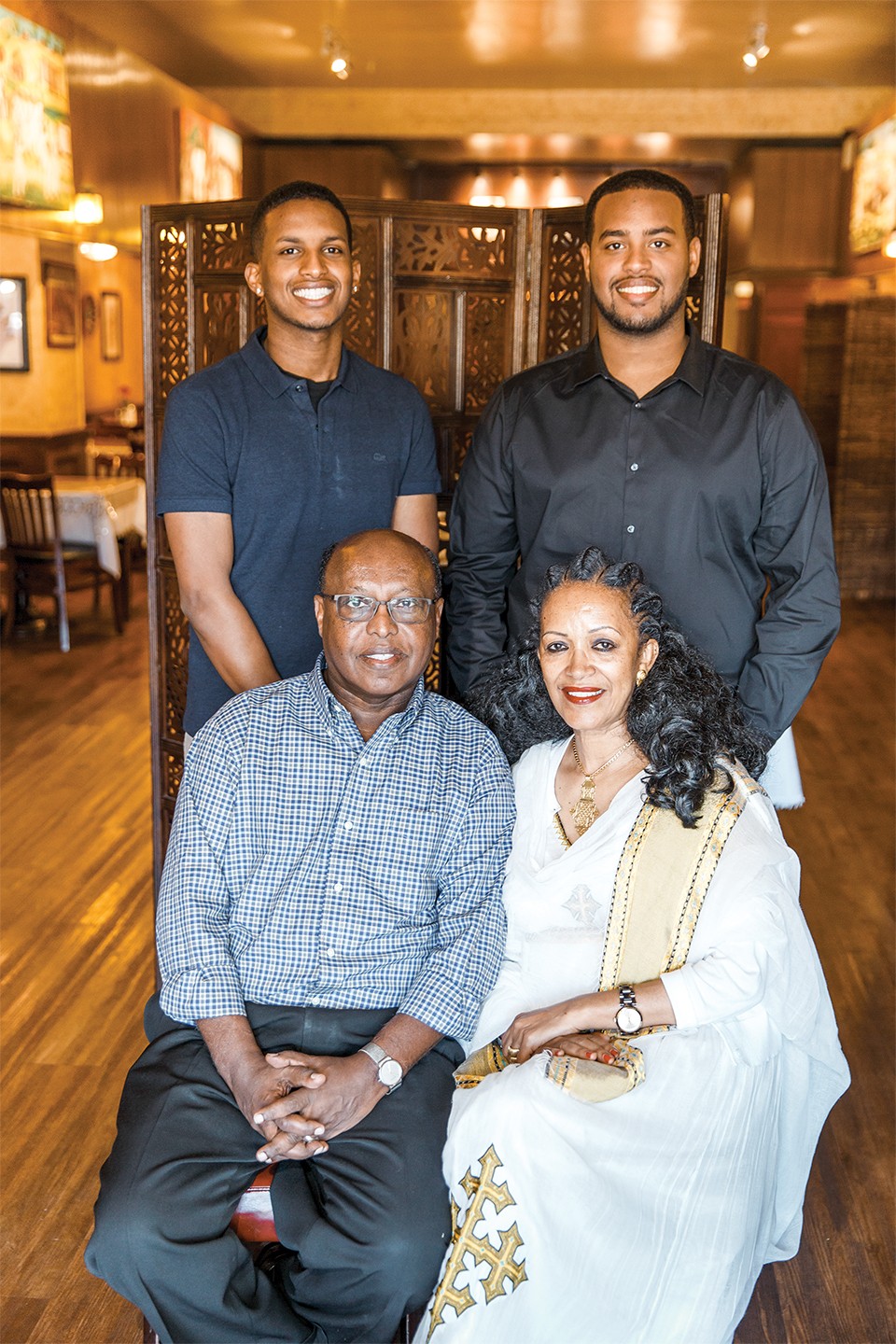

Kesete Yohannes, who, along with his wife Okba Yohannes, owns Asmara Restaurant (5020 Telegraph Ave.) in Oakland’s Temescal, has a different take on succession.

“I always wanted the business to be continued by the kids,” he said, explaining that he wouldn’t want to sell the business that he and his wife started more than 30 years ago to just anyone.

Opened in October of 1985, Asmara is the oldest continually operating Eritrean and Ethiopian restaurant in the East Bay. It was Okba’s idea to open a restaurant, because her family operated one in Zalambessa, a town on the border of Ethiopia and Eritrea. The couple, who immigrated from East Africa separately, are almost always present at their restaurant. It’s that consistency that has carried the quality of their food and service as well as a wise decision to buy the restaurant’s building early on that make Asmara one of the oldest restaurants on the block.

The Yohannes’ sons, Benyam, 28, and Yonathan, 25, have recently taken on a bigger role in the family business. Though he and his brother spent many childhood weekends at Asmara, Yonathan seemed surprised at his interest in his family’s business.

“It’s weird how I ended up here. I never thought I’d be in the restaurant industry,” he said, sitting in the restaurant’s newly renovated Asmara Lounge, which is set to operate separately as a bar with light snacks and open formally in October.

The sons convinced their parents to invest in the restaurant’s neglected bar, seeing great potential in a lounge on the busy block of Telegraph. Kesete is encouraged by their business-mindedness and is optimistic that the folks who have kept Asmara in business will also support his sons’ new venture.

“People know you and they’ll support your kids, too,” he said.

For the time being, he and Okba will continue to run the restaurant side of things with the eventual goal of training their sons further and reducing their own hours. Yonathan speaks in admiration of his parents’ institutional knowledge of their restaurant.

“I think it’s because he’s been doing it for 30 years, but the stuff I watch him do — I’m like, ‘How do you know exactly how much injera to make on a Tuesday, on a Wednesday?’ They really don’t waste anything,” he said.

[pullquote-1]At Hayward’s World’s Fare Donuts (20800 Hesperian Blvd.), Melissa Yam, the eldest of owners Kelly and Andy Yam’s three daughters, speaks with similar admiration about her parents.

“My mom has the most astonishing memory. My dad, too,” she said. “She can work by herself, take all the customers’ orders, and keep everyone entertained when she’s there.”

Kelly is unsure but discernibly hopeful on the subject of her children taking over the shop they’ve run since 1987. The couple, who arrived as Cambodian refugees fleeing the Khmer Rouge, were able to support their daughters’ education because of their business.

“I tell everybody, 31 years and three daughters,” said a cheerful Kelly, seated at one of World’s Fare’s old-school diner booths. Melissa equates World’s Fare Donuts to a community space.

“I grew up being babysat by a lot of different customers,” she said, adding that many longtime customers even attended her recent wedding. “There’s a lot of people who’d come to the doughnut shop every single day during certain hours of the day. I knew exactly who I’d sit with throughout the day.”

With their youngest daughter off to college, the Yams are considering retiring in the next few years. Their middle daughter, Ashley, is in a graduate program at UC San Francisco and Melissa is a high school teacher in Hayward, but both help out at the shop as they’re needed.

“Some families want the children to take over the family business but my parents always told me and my sisters that ‘no. We’re working for you. We have this business and we work really hard, so that way, you and your sisters can do whatever you want to do,'” Melissa said.

And there lies the dilemma. The prospect of giving their children a better life is often the singular focus that drives parents to work long days and nights in a brutally demanding industry. When they find remarkable success that lasts decades, the reward is bittersweet — their children have options, including opting out of their family’s business and forging their own paths.

Though she has no immediate interest in taking over the business, Melissa reflected nostalgically on the community that her mom has so lovingly cultivated over the years.

“I would be sad if that was lost,” she admitted. “When I was younger, it was definitely, ‘No, I don’t want to do the doughnut shop.’ But now that I’m a little older, I’ve come to a full appreciation of it. It’s not as much of a non-possibility as it was before.”