There are no official monuments to the Black Panther Party in Oakland.

This is despite the fact that

René de Guzman, the head curator of the Oakland Museum of California’s All Power to the People: Black Panthers at 50, insisted that the sprawling new exhibition honoring the Party’s legacy is not a polemic against historical attitudes toward the Black Panthers. But it undeniably opens with a statement.

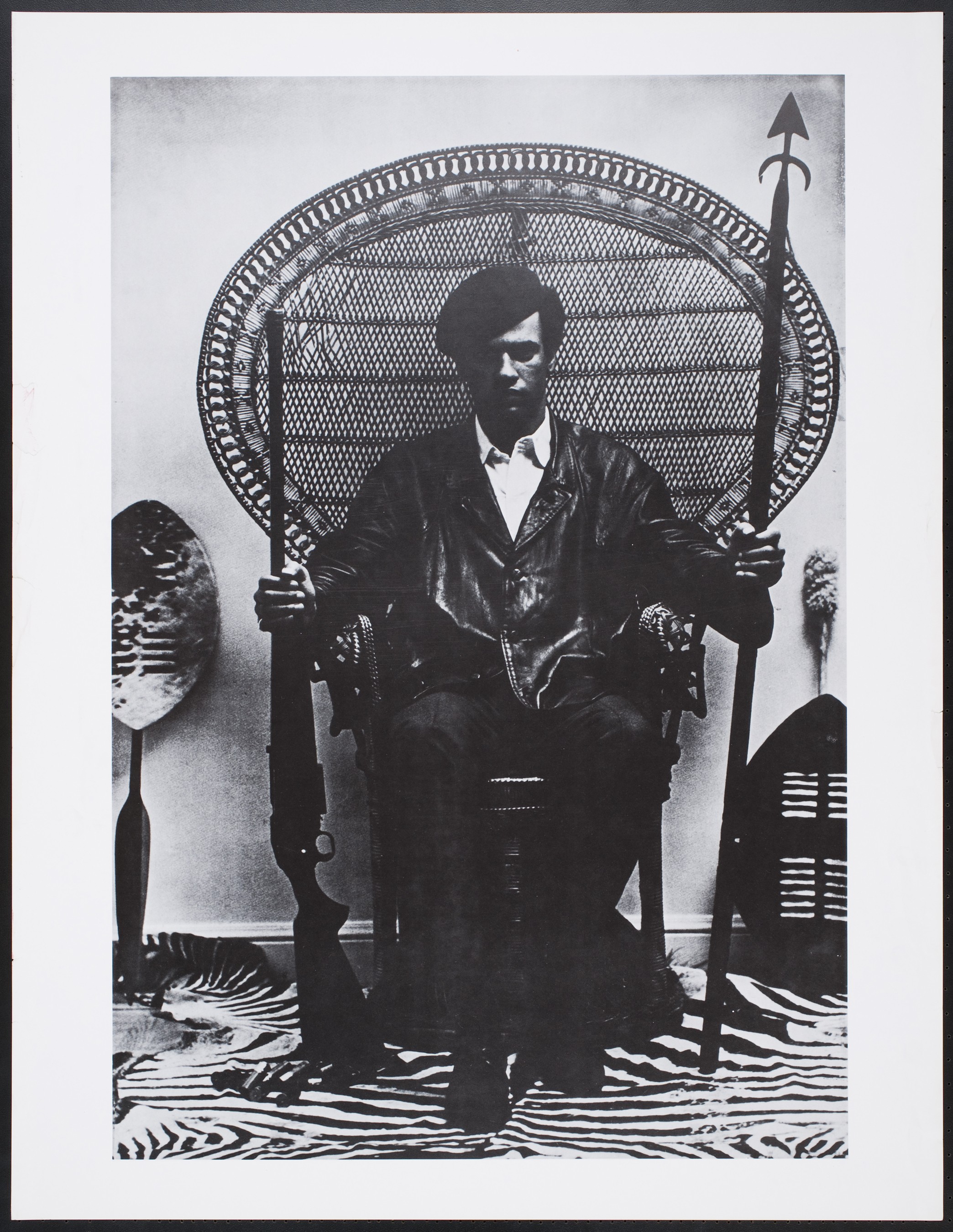

At the entrance is a bronze cast of a singular wicker chair, seated atop a small platform, like a golden throne fashioned for a porch. On the adjacent wall hangs a print of possibly the most iconic photo of Black Panther co-founder Huey Newton: sitting in an identical “peacock” chair atop a zebra rug, wearing a leather jacket, rifle in one hand, spear in the other, black beret aslant on his head.

The chair sculpture is a proposed memorial to the Black Panthers, created by artist Sam Durant and intended for the front of the Alameda County Courthouse — a historical site for Black Panther protests. And it’s not merely meant to be seen; viewers are invited to take a seat — to see things from Newton’s perspective.

This is an apt opener for All Power, a show that prompts viewers to not merely gaze upon mementos of a bygone Panther era, but instead enter into that world.

The Express walked with Guzman through the exhibition last week, and he was intent to communicate that his approach was not historical. Rather, he wanted it to be a show about the Panther’s cultural impact — a coalescence of informational ephemera, contemporary works inspired by the Panthers, and Party media presented as works of art.

In practice, it seamlessly blends together — which is unsurprising, considering the Black Panthers’ knack for merging aesthetics and political identity — be it their striking uniforms or the bold block prints of Emory Douglas.

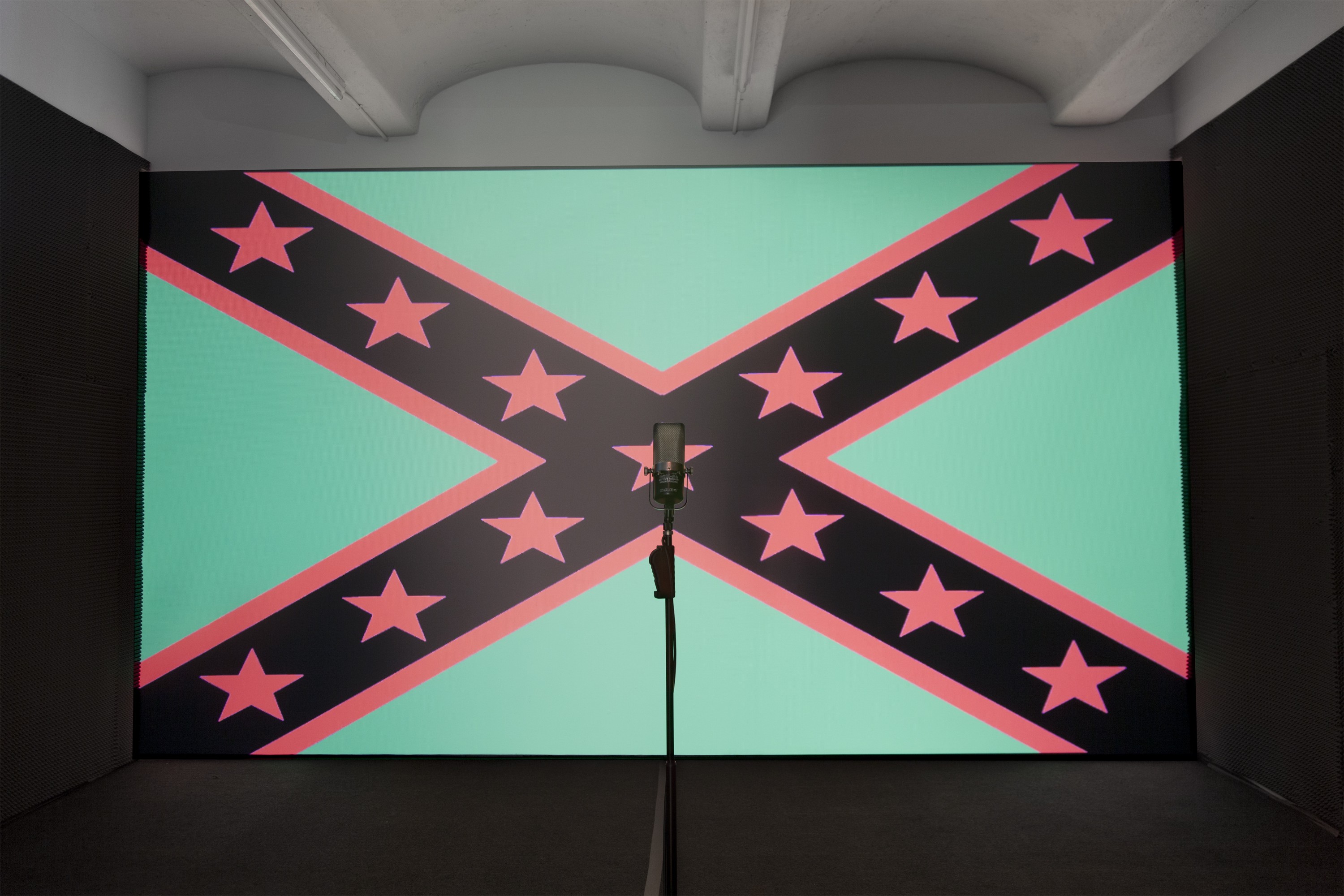

That’s not to say that the show doesn’t offer proper context. The first room quickly paints a picture of the racial climate that birthed the party: There’s an actual Ku Klux Klan robe, with a photo of the hate group marching through Richmond; an old map of Oakland colorfully marked to designate the areas where Blacks could not buy homes. There is also a wall emblazoned with the Black Panther’s Ten-Point Program: the list of demands that Newton and co-founder Bobby Seale presented to the U.S. Government in 1966. And, encased in a vitrine, is the original handwritten draft, a series of yellow legal-pad pages simply titled, “WHAT WE BELIEVE.”

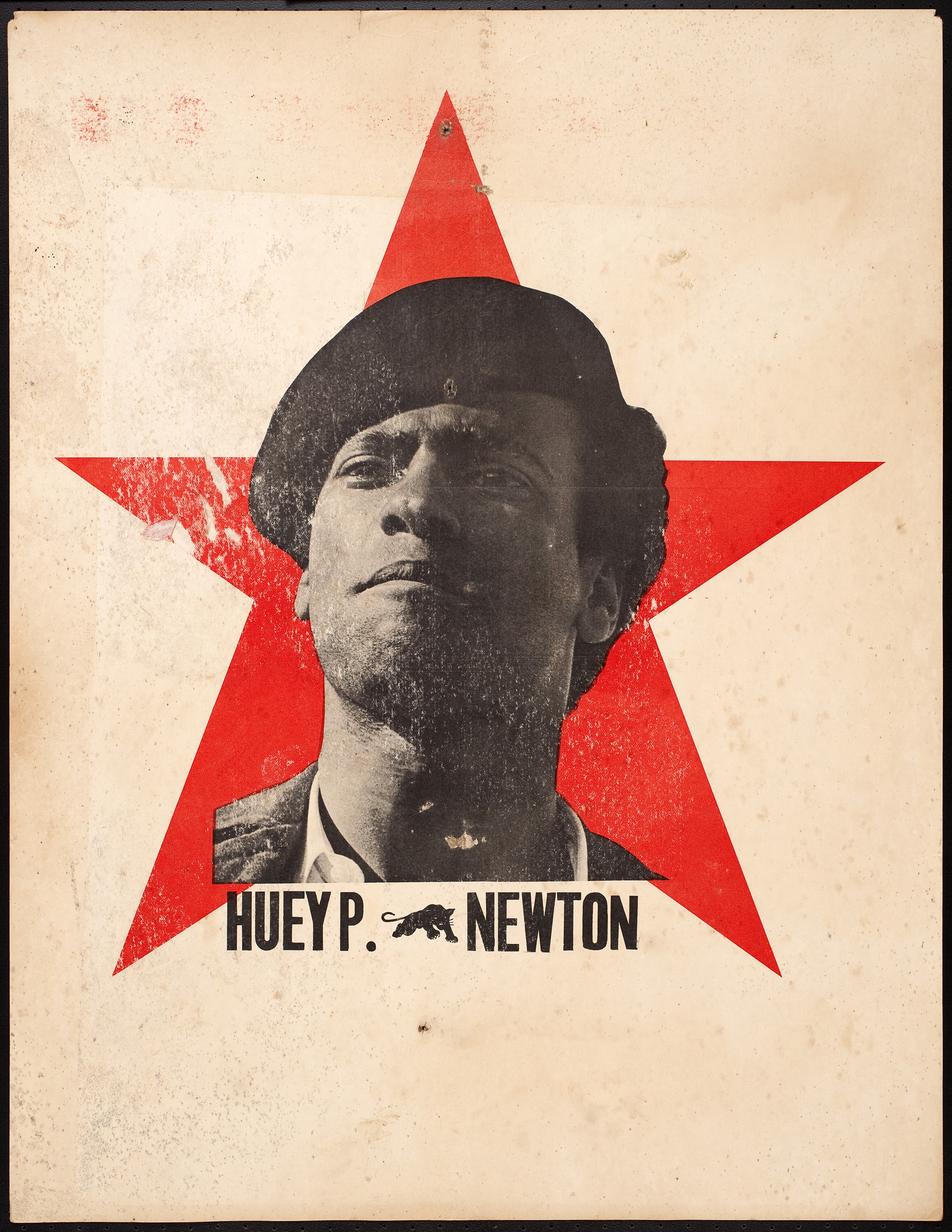

The exhibit also chronicles the Black Panther narrative, including covers of the Black Panther newspaper, posters that highlight the extensive allyships with other oppressed people (from Asian immigrants to Appalachian whites), and photos of female Panthers, who made up two thirds of the party.

In vast, multimedia exhibits such as this, the historical photos aren’t typically the most striking pieces. But the images in All Power — impressively assembled from a variety of private archives — visually anchor the show with stunning intimacy and energy.

Photos by Kenneth Green Sr., who studied photography at Laney College and, in 1968, became the first Black staff photographer at the Oakland Tribune, show the stirring student life at Laney and Merritt colleges at the time of the Panther Party’s formation. The images capture a simmering uprising: a crowd of young Black people surround two bloody bodies on a sidewalk, two dozen Black teens perched like birds atop a tall chain-link fence while a young boy watches from across the street, students dancing near picnic tables, a large group gathered on the steps of the Alameda County courthouse. Most of the photos have never been shown before, as Green’s son only recently discovered the negatives.

The exhibit also features contemporary works by powerhouses Hank Willis Thomas, Sadie Barnette, and Carrie Mae Weems, which reflect on the Party’s meaning in history from a few steps removed.

Viewers take in Constructing History: A requiem to mark the moment, a new commissioned video by Weems, by sitting in a church pew under a speaker, which makes it sound as if the artist is whispering in your ear. Her poetic narration accompanies a montage of violent human rights violations throughout history — from the indelible image of a Vietnamese girl running from a napalm attack to equally shattering videos of police-violence victims from recent years. It’s a reminder that collective memory is mutable, and that the Black Panthers were only one moment in a long, global struggle for civil rights.

This builds throughout the show, culminating in a section that incorporates the Black Lives Matter movement. A video features spoken word and interviews that include Black Lives Matter rhetoric, while Ellen Bepp’s paper cut piece, 100 Unarmed African Americans Killed by Police in 2014, is an obvious homage to the movement.

In 2016, there’s potential to draw many more parallels — to punctuate the show with a climax that boldly analogizes the Panthers’ work with the contemporary movement for Black lives. But, Guzman told me he didn’t want to act prematurely. After all, for all we know, the Black Lives Matter movement is still in its fetal stages.

Guzman’s apprehension makes sense considering that he spent three years working on All Power, researching and consulting former Panthers on how the Party should be depicted. When he began, the Black Lives Matter hashtag had never even been tweeted. It’s incredible how much has happened since — how many Black Americans have been shot by law enforcement, and how many fists have been raised.

Guzman described curating the show amid the the Black Lives Matter movement’s conception as “transformational.” And the anticipated audience for the show has undoubtedly transformed over those three years, as well; it now encompasses more allies — and more anger.

All Power arrives to viewers at a moment ripe for its content — so much so that no curator could have anticipated this relevance. And it delivers its message with a vital, powerful punch.

All Power to the People: Black Panther at 50 will be on view at OMCA (1000 Oak St.) through February 12. Free–$15.95. MuseumCA.org