In 2013, I had just returned from Europe. My marriage had ended and I was 43, frustrated, and sad. After spending a decade in Hollywood as an actor, I decided to move to the East Bay, where my brother was raising two kids in Berkeley. I remember getting a rankling cold that summer and after a week of hissing and hawking, my symptoms slowly began to fade. What remained was a single, swollen lymph node. It was a painless lump that settled and slowly flourished on the right side of my neck beneath my jawline. It concerned me in the way that lumps tend to. As it swelled, so did my anxiety about it.

It would occasion two visits to a local clinic, a dentist, and the emergency room — where it was chewed over, prodded, pricked, and biopsied — before an Ear, Nose and Throat doctor wordlessly placed a sheet of paper in front of me. It read: Metastatic Squamous Cell Carcinoma.

“What does it mean?” I asked, with a fresh lump in my throat.

“It means it’s cancer.”

Until that time, the only person I knew of with throat cancer was Michael Douglas, who declared he’d been stricken as a result of his enthusiastic and breathless devotion to the art of cunnilingus. His revelation was only part truth. (Douglas later said he actually had tongue cancer.) The new wave of throat cancers in men is a hidden outgrowth of a particular strain of the human papillomavirus (HPV) that is both undetectable and untreatable.

According to the CDC, nearly all sexually active people will get HPV at some point in their lifetime. P. Daniel Knott, the director of Facial Plastic, Aesthetic and Reconstructive Surgery in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery at UCSF Medical Center, notes, “There are over 150 different types of HPV, and certain types can lead to cancer — albeit with a very long and innocuous incubation period of more than 20 years.” Ordinarily, HPV is cleared by an able immune system, but those with a high-risk strain of oral HPV can develop oropharyngeal cancer — meaning the back of the throat, including the base of the tongue and tonsils. “Persistent infections are the most problematic, and smokers and immunosuppressed individuals are particularly susceptible, although anyone can develop a persistent infection,” said Knott. Oral HPV is more prevalent among men than women, and is believed to be spread largely via oral sex. It’s estimated that HPV is responsible for 70 percent of oropharyngeal cancers in the U.S., and while the risk remains relatively low, the number of oropharyngeal cancer cases is expected to outnumber cervical cancer ones by 2020.

[pullquote-3]Historically, oropharyngeal cancers signaled a death knell. For this newer strain, I was told that my chances were more optimistic but that the treatment was “pretty brutal.” My prognosis was 50/50.

If I was wondering before in which direction I wanted my life to go, it was now clear: away from death.

Trauma is, for the brain, like a tattoo. It scars and can last forever. As time passes, it fades and sometimes becomes distorted. There is one thing from that day that I remember with absolute clarity. My diagnosis was heralded by an instant, booming rain.

I was told that the first order of business would require the removal of my right tonsil, which would be sent to a lab for testing.

“We’ll have to take out all those lymph nodes, too.”

To illustrate, the doctor made a yanking motion like he was firing up a chainsaw. He then stepped outside to take a call. He discussed his lunch with fervor. I walked over to a mirror that hung on the opposite wall and had a look at myself. Flushed and unplugged, I stared at the hulking gobstopper that now had a name and a function.

What will become of you?

I scheduled the tonsillectomy and stepped out into a dripping courtyard.

Over the next few days I passed along the news to family and a few friends. These talks were mostly just plain sad. But at the center of each was a soft warmth. Wagons were circled as were dates on the calendar. There was an appointment with an oncologist, a radiation oncologist, and an oral surgeon.

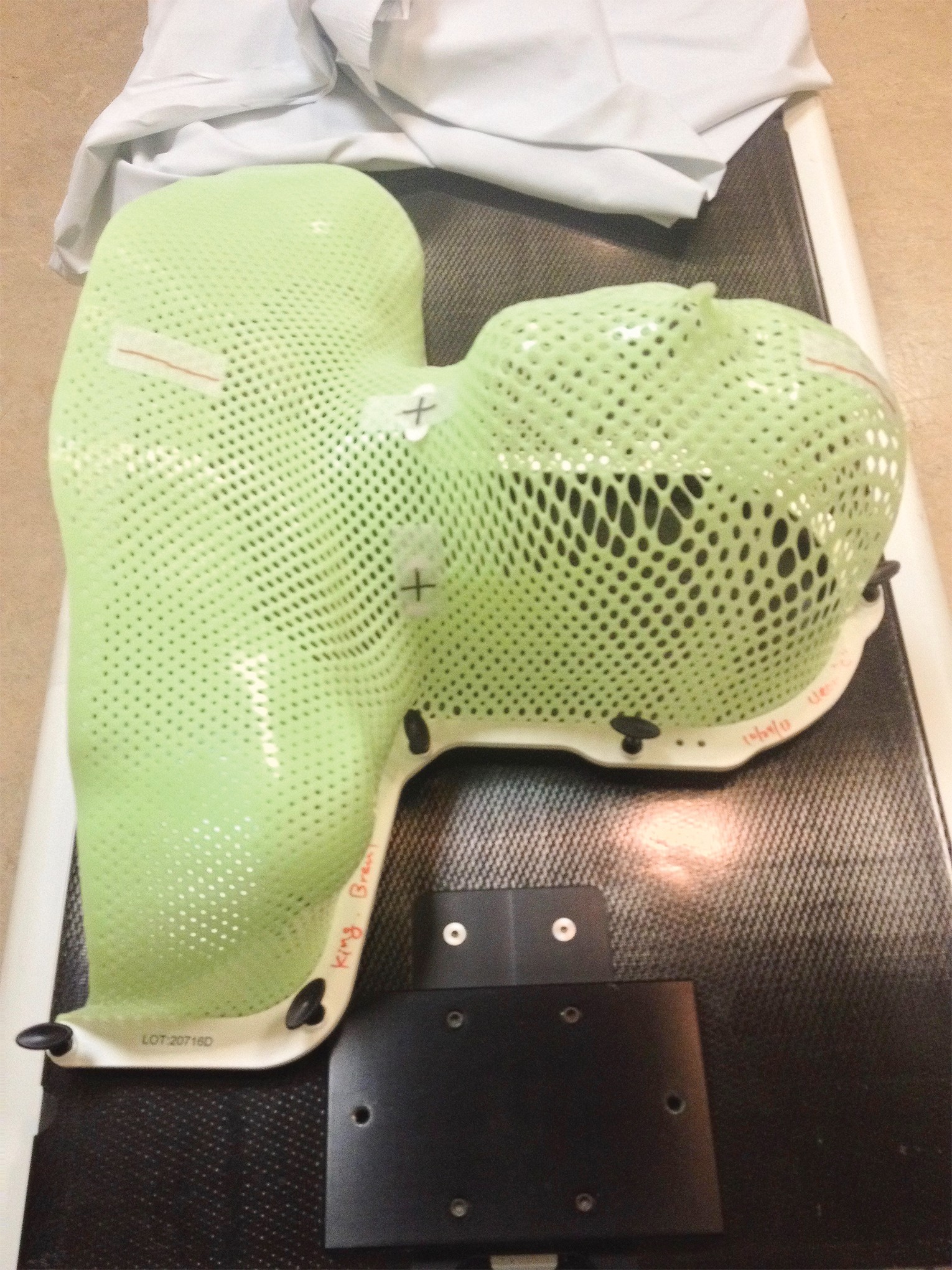

When the tonsil was tested and shown to be non-malignant, a PET scan was scheduled to find out if the cancer had spread to other parts of my body. I lay still on a platform while a scanner clicked and droned around me. It would be three days before my radiology oncologist notified me that the scan revealed a small spot at the base of my tongue. Rather than surgery, I was prescribed radiation treatment with supplemental chemotherapy. Five days a week for six weeks I would receive a mega dose of radiation to my head and neck. Once a week I would endure an infusion of nuclear sludge (Cisplatin). I was told that during this time I should expect that my taste buds would fizzle out, my saliva glands would wither and fail, and my throat would be become a dry, dusty cranny. I would also lose a swath of hair along the back of my neck and my beard would fall out. At this same visit, I was tattooed and fitted for a mask that would be placed over my head and shoulders and clamped onto a table to immobilize me during the radiation treatments.

My general oncologist was to oversee the chemotherapy and advise me on the results of my labs. (I would require weekly blood tests to monitor my cell count and thyroid.) He was 30 minutes late for our appointment and came into the room laughing loudly. He was showboating for a younger, blond female colleague who was shadowing him for the day. He gave me a prescription for nausea, one for pain, one for anxiety, a steroid, and a laxative. The meeting lasted less than ten minutes. I would never see this man again.

That Sunday, my brother hosted a small get-together in my honor — just a few friends and family members. My throat was still sore from the tonsillectomy and it was too painful to swallow anything but crushed ice. Also, the king-sized bottle of codeine cough mixture left me feeling gauzy and removed. I remember saying hello to everyone and then going upstairs and falling asleep on his bed. In the moments before I dozed off, I realized that future Sunday dinners would carry on no matter what happened to me. There would be movie nights and birthdays and brunches. A new iPhone, a new Star Wars movie, a new season of The Bachelor. The realization that the world will keep spinning quite merrily without you is a commanding one.

[pullquote-1]Next was the removal of my lower wisdom teeth. They sat squarely in the radiation field and were considered “problem” teeth. I was told that any extractions post treatment would mean big trouble. The radiation beams targeting the lymph node and the base of my tongue would slowly dissolve the cancer cells while also ravaging the surrounding bone, blood vessels, and tissue. Future dental work of any kind would pose a risk as my body simply would not be able to heal itself. After the surgery, I was given two whole weeks to heal before treatment began. In this interval I was supposed to fatten up. I would need the extra weight. It was challenging because my throat was still tender and I couldn’t really chew after my teeth had been removed.

Encouraged for the first time in my life to gorge myself, I was helpless to do so. In these two weeks, I realized what the anxiety meds were for. (They were supposed to be for the radiation procedure, which is claustrophobic and nerve-wracking for some.) For me, the anxiety came with the slow, sinking feeling of really knowing you are sick.

The first day of my radiation therapy went well. That’s to say, I didn’t panic. The tattoo I received (a tiny black dot) was used to align the plastic mask that was placed over my torso and locked onto the surface of the table. The radiation beams are programmed to be so precise that you have to remain essentially frozen as the machine spirals around you. (They threw a blanket over me — people were always throwing blankets over me.) The whole business lasted about 15 minutes. Data was entered into a laptop and then I was free to go.

Chemotherapy, on the other hand, was a bit more in your face. The gravity of the procedure hit when a nurse in rubber gloves and a hazmat suit arrived. The drug was in a plastic pouch that may as well have been labeled with a skull and crossbones. She handled it like a time bomb. It was administered intravenously and bookended by saline infusions. I was given my own recliner, a blanket, and a personal television. After four hours, I was allowed to leave until the following week.

The thing about these treatments is, at first, you don’t really feel anything. Just a faint promise of something. The effects of the radiation took a couple of weeks to set in. The chemo announced itself in the first few days. By the end of the first week, I was introduced to a rocking, foaming nausea that would last for days. My ears rang and the cyclical vomiting left me exhausted. The urgency and force of it was impressive. At one point, I thought of procuring a lobster bib for all the splashback. I marveled at my body’s abilities.

By the second week I began to feel a fatigue and a sense that a turning point was upon me. On the day before Thanksgiving, my brother and I visited Doughnut Dolly in Temescal Alley. It was the day I realized my taste buds were fading. He ordered the Mexican chocolate. I had the chilled wood glue.

The next morning I woke up to a biblical throbbing. The whole right side of my face was bloated beyond recognition. I was staring into a funhouse mirror and it was plain to see that the site of my former wisdom tooth had become infected. In fact, it had become abscessed and needed to be drained. At the dental office I was informed that bone dust, left behind, was likely the culprit. Without anesthesia, an oral surgeon and his assistant flushed the site with salt water. For those 30 minutes my whole body rattled from the pain. I was prescribed a whopping antibiotic and given a two-day respite from the radiation. By the time I arrived for my next appointment, I had lost nine pounds.

When your taste buds go, that is when they cease to function. It’s not that you don’t taste anything; it’s that everything tastes like rotten newspaper. Even water becomes unpalatable. Add to that a blistering sunburn on the inside of your throat and you’ve got a hell of chore on your hands trying to stay hydrated. By this stage, my saliva glands had been scorched as well, and all my nourishment came in the form of Ensure Plus High Calorie Shakes. The bottles read strawberry, vanilla, butter pecan, but each mouthful was like throwing back a shot of molten lava. The ringing in my ears swelled and my jaw continued to smart and spasm. Three weeks in, three to go.

[pullquote-2]

“Oral mucositis is probably the most common, debilitating complication of cancer treatments, particularly chemotherapy and radiation. It can lead to several problems, including pain, nutritional problems as a result of inability to eat, and increased risk of infection due to open sores in the mucosa. It has a significant effect on the patient’s quality of life.”

So says The Oral Cancer Foundation. What they don’t describe are how thick bands of mucous begin forming in your throat after the first weeks of treatment. It comes on so quickly that within a few days I had to keep a Mason jar on my bedside table, which I filled each night. It was like trying to swallow gobs of flaming egg whites. Sores soon developed and multiplied and it became impossible to swallow anything. After a few days, I became so undernourished and dehydrated that I began to hallucinate and had to be dashed off to the emergency room for IV hydration.

Days later, the skin on my neck began to peel and fall away. What was happening on the inside of my throat was now evinced by the texture and complexion of the thin layer of skin cells that were cast away in sheets. I was doing a fair amount of chin stroking during this time and in the waiting room for my next chemo treatment, I noticed a collection of curlicues at my feet. My beard was falling out. By the end of the day only a few stubborn whiskers remained.

Christmas was fast approaching and I had moved into my brother’s back house. It was without a toilet and, so that I could be successfully cordoned off from everyone, we set up a drop-arm, commode chair on wheels and strung it up with colored lights. It was in lieu of a tree. It was both festive and absurd.

On my final day I was driven straight from radiation to the emergency room at Alta Bates hospital, where I was treated with more IV fluids, oxygen, and morphine. I would remain there for four days and was released on the eve of the new year. I had lost 60 pounds.

When I arrived home at my small apartment in North Oakland, I began to construct a daily routine. It would be three months before another scan would reveal if the treatment was successful. By now the effects of the pain medication were diminishing and it was difficult to sleep for more than a few hours at a time. I would get up in the middle of the night and swallow spoonfuls of olive oil to keep my throat from drying out completely. I’ve never ached more for the passage of time. I bought a humidifier, used nasal sprays and throat misters, tried acupuncture, and nibbled on marshmallow root. The ringing in my ears turned them sore and the pain in my jaw continued to surge.

Saliva is a natural disinfectant and I was no longer producing enough to wash away bacteria and other germs that could cause my teeth to decay. A trip to the dentist had been scheduled so that I could be custom fitted with fluoride trays. It was on this visit that they discovered a small bit of exposed bone where my right tooth had been removed. The radiation had prevented it from healing properly and a panoramic x-ray was ordered.

Osteoradionecrosis is defined as bone death caused by radiation. It was mentioned early on as a possible side effect and the word itself occasioned such a profound sense of dread in me that I had hardly even dared to think of it. The x-ray showed that the infection had not only failed to heal but had funneled down to my jawline. I was told my only hope was to stop it from progressing. I got a second opinion. And then a third. The outcome was always the same: My mandible was slowly turning to dust. For the first time, I was scared.

[pullquote-4]Since my diagnosis, I’d had plenty of time to consider that I could die. I had decided early on that cancer does what it wants. I wasn’t putting up a fight, just enduring its execution. I’d even prepared for it. I cleaned house, read old love letters. What I hadn’t considered deeply was how many things are worse than death. If I lost my jaw, I would never eat solid food again. I may never speak again, or kiss again, or love again. I would be disfigured, and the horror of my reflection began to keep me awake at night. I found a therapist. I read books written by great survivors: Man’s Search for Meaning, The Diving Bell and the Butterfly, Autobiography of a Face. I once spent an hour in Moe’s Books on Telegraph Avenue reading the last chapter of Roger Ebert’s autobiography. (Cancer got him, too, but not before it took his jaw. He was left silently slobbering in one room while his wife took her meals in another.)

Meanwhile, I got a clean scan. “No evidence of disease,” they say. I was cancer free. The treatment was considered a success. I was still too sick and tired to return to the workforce and it was only with the help of my family and my savings account that I was able to devote myself to myself. I started going to the YMCA five days a week. At night I read medical journals and case studies and searched for alternative treatments online. Still, there was a creeping numbness along the right side of my face and the nerve that runs along the jawline began to tingle. It was still too tender to chew on that side of my mouth so my left side did most of the work. I would then kick it over to the right side to give it a little workout before I swallowed. Slowly my taste buds began to return. I made fast friends with custards and crème brûlée. I became an authority on cream filling and began reviewing local doughnut shops on Yelp.

During one of these late nights I discovered something called osteomyelitis. It’s a bone infection that is treated with IV antibiotics. If I had an infection then maybe this was a way out. I had to try. After speaking with my radiology doctor I was referred to an infectious disease specialist who laid out the risks involved with the procedure. It would require the placement of a peripherally inserted central catheter or PICC line. A small tube would be inserted in a vein in my arm, travel up toward my shoulder, and curve softly until the tip rested against my heart. I ran the risk of further infection and blood clots. I was told it was inadvisable.

This was the first time that I would have to make a case and fight for a treatment that others deemed foolhardy. It would not be the last. I was reluctantly prescribed a 30-day dose of IV antibiotics and the PICC line was scheduled to be placed.

I was to be visited by a nurse once a week who would draw blood, clean the site, flush the line, and change the dressing. My nurse was a guy called Romeo. He drove a BMW and smelled like a men’s magazine. The line was fixed to the inside of my bicep and secured with a length of gossamer netting. It was concealed under a T-shirt and once it was in place, I didn’t feel a thing. For the first couple of weeks, the blood tests revealed nothing out of the ordinary. Then, on the third week, I received a message from my doctor. This was it! I imagined an unprecedented admission. A turning of the tides that defied all conventional wisdom. Something that began with, “You’re not going to believe this…” or “I don’t mind telling you, I’ve never seen anything quite like this before…” I turned batty with expectation. When she told me my potassium levels were low, I could only shake my head and smile: “So, eat two bananas and don’t call me, I’ll call you?”

The whole event passed without fanfare and without results. Another x-ray after the procedure showed that my jaw was continuing to slowly disintegrate.

For this reason, I was sent to meet with a head and neck surgeon who explained a surgical procedure called a fibula free flap. It’s a reconstruction of the mandible that involves the removal of the dead section of my jaw, which would then be replaced with a bone taken from my lower leg (the fibula). It would be sculpted, plated, and screwed into place and, with a little luck, would preserve its basic functions. He also prescribed a series of medications that, taken together, was a controversial but emerging protocol for osteoradionecrosis. It involved taking vitamin E (daily); something called Pentoxifylline (also daily), to increase blood flow; a bisphosphonate, usually prescribed for osteoporosis (five days a week); and an oral rinse called chlorhexidine, which I would swish and gargle four times a day. I left the office in state of lukewarm catatonia.

That evening I sat up reading about the surgery, and it was then that I was introduced to hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBO). It was suggested as a part of the post-op protocol. It involves lying in a pressurized, clear acrylic coffin while breathing in pure oxygen. The idea is that it promotes healing in irradiated bone by increasing the amount of oxygen in your blood. It’s both controversial and expensive. As I lay awake one night reading an article on microvascular surgery, I had a thought: Why not try hyperbaric oxygen preemptively to see if it might stimulate the blood vessels in my dying bone? Why wait until after the surgery? I hadn’t been given any indication that I could heal myself. I was assured over and over that the best hope was to stop it from progressing. But what if? What if medications and the PICC line and the HBO therapy combined could regenerate cell growth? After I pitched my radiology oncologist, who agreed to back me up, I called a facility in Alameda and made an appointment for a consultation.

My arrival time was set for 8:45 a.m. I had been asked to come 15 minutes early in order to fill out paperwork, but when I arrived the parking lot was empty and the office was shuttered. I sat on a wooden bench and softly fumed. An hour later I was led into an exam room and 45 minutes after that I was introduced to a retired vascular surgeon. He had the appearance of a balding, Bond villain. I laid out my case with care and tender persuasion. With a smile, he told me that there was not enough substantial data to justify HBO for my predicament. I redoubled my efforts and patiently explained that two other doctors had offered to provide me with a referral. Finally, he went slack, shook his head, and relented with a mild tut.

On the first day of treatment I was given a single hospital gown and a pillow. This was all that was allowed in the chamber. It was explained that it would take about half an hour to pressurize, I would breathe pure oxygen for 90 minutes, plus another half-hour to depressurize. The experience of being in the chamber was claustrophobic. As it begins to pressurize, you hear pops and cracks in the acrylic, which awakened many a paranoid fantasy: ruptured eardrums, blown lungs, explosions, fiery death. There was a two-way intercom inside and a flat-screen TV mounted outside at the foot of the hull. The only options were daytime television, which I hadn’t seen in years and only added to my distress. Caffeinated talk-show hosts and garbage game shows. Judge Judy! This I couldn’t bear. I was granted permission to hook up a DVD player and decided to revisit the French New Wave. Godard, Demy, Melville. They would be my bedfellows. If my ears bled or flames consumed me, at least I would be in fine company. And so, for the next ten weeks, Monday through Friday, I began a new regimen in an effort to save my jaw.

The space held two chambers and they were always filled. The routine began as such: You arrived, slipped into your gown, and took a seat in a kind of on-deck circle. In the beginning, my cohort was a cancer survivor whose teeth had begun to crumble and fall out due to radiation. She always covered her mouth when she spoke and laughed. She was soon replaced by a prickly older woman who elicited much tittering and eye-rolling from the staff. Part of her tongue had been removed and her time there was in preparation for some future ghastly operation. Legions of wounded were admitted to these chambers daily and each of us held onto a shared longing.

After the treatment, I would have to wait four more months before I would receive another panoramic x-ray of my jaw.

It was a long four months and I spent the time moving anonymously through the city. As I began to get more interested in food, I made a ritual of going to the farmers’ market in Old Oakland. At first I would walk along the sidewalk scanning the stalls. It’s always flowing and peopled and committing is kind of like stepping into a hurried stream. I made a mental list (avocados, radishes, beets) and always started by the blueberry samples. They were warm and sweet and I would linger for a bit next to a flower stall where fresh lavender stood in bunches and flavored the air.

I had grown pretty isolated by this point and rarely spoke to anyone who wasn’t requesting blood or urine. I felt ruined. It’s difficult to think about making new friends when you know your face is about to be rearranged. Not a day passed when I did not consider something else that could be lost.

Would I ever be able have children?

What would I have after they took away my jaw? My eyesight, a full head of hair, my memories. Who can relate to this kind of thinking? Who could I talk to about what was happening to me? I could barely relate myself. It never fully hit me. It just kept dawning on me over and over again.

[pullquote-5]I walked around Lake Merritt. I took myself to the cinema and cried in the dark. I felt totally invisible. (It was nice to feel invisible.) I was an outlier in a man suit.

During this time, I also began having nightmares again. Most of what I remembered involved part of my face coming off. It would break away like a scab and what was left was scarred and misshapen. It was a warped and distant image of myself that came with a specific feeling: “This is what you look like, get used to it.” I began to wake up in the early morning hours and would sometimes hear a voice crying out. I began to suspect that it was me who was screaming into the night and I downloaded an app called Sleep Talk. It’s designed to record sleep talkers, snorers, bad dreamers. It would reveal some of the most primal and terrified sounds a body can make. It was a version of me. It was the sound of my fear.

It was two weeks before my follow up when I noticed some blood in my stool. It was a bright red streak that sent a familiar chill of panic through me. It happened three days in a row. I took pictures and made an appointment with my primary doctor. He advised that, given my history, a colonoscopy should be performed. It was scheduled almost three years to the day that I was first diagnosed.

On the day of my x-ray I prepared a thermos of coffee and cycled to Mountain View Cemetery. It had, by now, become one of my favorite places. That day I sat silently on a hillock and stared out over a rising strata of morning fog. I sat for a long time. I remember feeling a profound happiness resting within me and suddenly caring a thousand times more deeply about everything around me. It’s a feeling I wanted to go on and on.

I met with the technician and then I moved to a waiting room and leafed through some beauty magazines. After, I was led into an exam room and waited some more. Ten minutes later I was staring at a computer screen with my surgeon and was dazzled by the latest image. I had grown used to seeing the faint, shadowy void that snaked down the bend in my right mandible. Today we looked at a photo that revealed an almost total regrowth of the bone on that side. It was miraculous and I was flush with feeling. The surgeon sat in a chair opposite me and smiled.

“Congratulations.”

He praised my perseverance and shook my hand. He seemed to me to be speaking in calligraphy.

“You’re a success story.”

He couldn’t explain to me why the bone had healed: Was it the medication? The HBO therapy? We couldn’t know for sure. What mattered was that, for now, it appeared as though I would get to keep my jaw. I felt like a cross-country runner collapsed on the happy side of a finish line. Like I had been running for years across an unnatural terrain of goosebumps and jitters. It was relief and disbelief fused and peering back at me in the form of my smiling bones.

And how did I celebrate? How did I mark this tiny miracle? With apple juice, chicken broth, and four liters of high-octane diarrhea maker. My colonoscopy was scheduled for the next day and that required 36 hours without solid food.

I was nervous about the procedure but also because I lied about having a ride home. They’re not supposed to proceed unless you’ve arranged for someone to pick you up. My cousin was out of town, my brother was unavailable. Anyway, I couldn’t find anyone and I had to lie. (I had a nice one-liner teed up if the time was right: “I figured you guys would be able to tell if I was full of shit.” The time was never right.)

When they wheeled me in, I had a quick word with the doc and they had me lay on my side. Then the lights went out.

A few moments later I was awoken and the room seemed to be in a state of hyperarousal. I was fuzzy and uncomfortable as the situation slowly began to gel. The probe was still inside me and I was directed to a monitor, which showed a small but bilious tumor. I watched it get tattooed and biopsied before they slowly backed out the scope. Still in a smog of anesthesia:

“Good thing you came in.”

“Glad we got it early.”

“You got bad genes, man.”

“It doesn’t get much earlier than that.”

They whisked me away behind a curtain and handed me a wad of baby wipes. I got dressed.

A nurse came in to ask if there was another number they could call to contact my phantom ride home. At this point I came clean.

“There’s no one coming.”

I apologized and said I had no choice. They immediately told me not to worry and began peppering me with questions. They wanted to be assured that I was clearheaded before they let me go. A nurse in scrubs wearing a huge diamond ring came over and put her hand on my knee.

“You liar.”

She said it with a wink and I immediately tried to apologize again but she wouldn’t hear it.

“We’re gonna put a rush on that path report,” she said. “We’ll have the results by Monday.”

She led me to a back door that opened on to 14th Street and Broadway.

California sunshine feels specific when you’ve just been told you have cancer. It feels unbefitting and a little tasteless. Here I was back on the street, ghosted again.

[pullquote-6]Whereas the first time around I felt like circling the wagons, this time was different. I felt like I was circling the drain. I didn’t want to advertise. I told only my immediate family and kept the details on a need to know basis. Yes, it was colon cancer. There would be an operation. I may need chemo but it was too early to tell.

The surgery, a right hemicolectomy, would be done laparoscopically. A large portion of my colon would be removed and I would remain hospitalized for four or five days after. My sister would fly in for this one and be by my side.

I was certain that the cancer that invaded my body three years ago would kill me and I was so assured for the last two that I would lose my jaw. And now I kept trying to push away the very powerful feeling that this procedure would finally be the death of me. It’s funny, but I hadn’t allowed myself to see a future. I couldn’t imagine a family or any happiness or successes unborn. When people say they have a lot on their minds, that’s how I felt. Except it wasn’t about work or kids or bill paying. It was about death and impossible pain and being unable to take care of myself or recognize myself when I looked in a mirror.

That morning I stood for a long time staring at my reflection. The wilderness of my brow, those weathering eyes, the frozen wrinkle of a smile. For that moment I was okay. That was the only thing I could be absolutely sure of. I arrived at Summit hospital at 6:30 a.m. A starchy hospital gown and a blanket had been laid out for me.

We’re all hanging from a different thread and when you are as sick as I was, for a time, those threads are made visible. What matters gets refined. And what remains is never the same: a mirror’s reflection, a trip to the farmers’ market, a swallow of crème brûlée.

It’s now been a year and a half since I was given another clean scan. No evidence of disease. The only evidence is a four-inch scar above my belly button. Chemotherapy wasn’t needed because the cancer had yet to spread to other parts of my body.

That said, I can’t say that I feel out of the woods or that I ever really will. With cancer you have to wait five years before they give you an all-clear and declare you a “survivor.” The latest diagnosis reset the clock, and the long-term effects of radiation can present themselves at any time. And that list is long.

Looking back, maybe the colon cancer was bad luck. Or bad genes. The HPV-related throat cancer was not. A vaccine exists that can forestall these high-risk, cancer-causing infections. “Very few types of cancer can be prevented by a vaccine,” noted Dr. Knott. “The HPV vaccine is most definitely an anti-cancer vaccine.”

It’s generally provided for both boys and girls beginning at the age of 11 or 12 — or before they reach an age of potential exposure to it — and is given in two or three doses. “Anyone who is a minor or anyone with children below the age of 18 should care about this vaccine, as it can prevent the spread of persistent infections and may also prevent the insidious development of throat and cervical cancers more than 20 years down the road,” said Knott.

“I’m certainly going to vaccinate all of my children.”

Absolutely unbelievable article Brent King. God bless you!