In Berkeley, on the feast of Epiphany, it was pouring down rain. This was shortly before Donald Trump’s inauguration, so we decided to pay a visit to the Newman Parish Hall Church. Inside, parishioners gathered in a freezing-cold concrete bunker, designed in the mid-1960s by the brutalist architect Mario Ciampi.

We prayed, too. We sang. We held hands. We were scared: Does brutalist architecture speak to us in tones that reflect our political desperation?

Anyway, since the body and blood of Jesus Christ hadn’t quite staved off the draft blowing through the building, 79-year-old parishioner Dan Cawthorn, who has been attending the church since 1991, was trying to warm up over coffee and donuts upstairs after mass. Cawthorn said he felt about the building the way he feels about good Scotch: It’s an acquired taste.

At first, it’s off-putting, but then you’re like, “Wow,” and you discover its wonderful flavors.

“But for me, it evokes this concept of the Holy Mud,” he explained. “Our first perception of dirt is that it’s unclean, and we want to avoid it. And that’s something, I think, that the architect is trying to share with us — that our dirt is alive with life. You’re dust, and to dust you will return. But if you understand the dirt, then you’ll understand that the dirt is alive. And that’s transformative.”

Wow. Take us to Dirt Church, Cawthorn. Show us fear in a handful of dust.

Our point is that Brutalism is holy, spiritual, and there’s a lot more to the style of architecture in the Bay Area than you might imagine. Even the Bay Area Rapid Transit system itself is a concrete octopus wrapping its late-capitalist tentacles around our topography’s delicate face.

Sadly, though, people talk a lot of shit about brutalism. Prince Charles of England has been particularly outspoken, calling buildings such as the National Theater on the South Bank of the River Thames “monstrous carbuncles.”

But the joke’s on you, Prick Charles, because brutalism is a form of architecture undergoing a massive resurgence.

“Brutalism is Back,” proclaimed Nikal Saval’s October 6, 2016, article in The New York Times. And a December issue of the New York Review of Books listed half-a-dozen coffee table tomes about brutalism, including one nine-pound baby running to more than 700 pages, at $125, in Martin Filler’s article, “The Brutal Dreams That Came True.”

Nevertheless, there are less-enthusiastic folks in the Bay, who aim to dismantle or tear down our brutalist legacy. To which we ask: Why no concrete lurve?

What Is Brutalism?

You’ll want the details, for the next time you’re discussing concrete over a bourgie dinner, so: Brutalism’s name comes from France. An architect called Le Corbusier started using exposed concrete surfaces in the 1950s to structure his buildings, and because the style was called “béton brut,” or “raw concrete” in French, a British architecture critic named Reyner Banham took the last word, “brut” or “raw” (because the French flip their adjectives and nouns around), and he adapted it, then, into “brutalism.” This was a way of describing a whole new style of architecture, one created predominantly out of poured, raw concrete, which would soon sweep its way across the world. That’s defined brutalism. Don’t quibble with us.

Concrete architecture was all about raw honesty in the wake of a horrific second world war, when the truth was euphemized. Or at least that is what Banham essentially wrote in his essay on “The New Brutalism,” published in the Architectural Review in 1955. He also went on about brutalism’s “bloody-mindedness” and “ruthless logic,” which, for a white guy writing in an architectural journal in the Fifties, qualified as pretty avant-garde and shocking.

The cultural critic Jonathan Meades points out that the Nazis were in fact the first to really employ concrete on a brutalist scale, and in a brutalist style, in his BBC Four documentary Bunkers, Brutalism, and Bloodymindedness: Concrete Poetry, which is available illegally on Vimeo. Meades, who emailed us from one of Le Corbusier’s original brutalist structures in France, told us we were welcome to quote from his documentary for this article. But we recommend you simply go there and watch the entire thing for yourself, because it’s too good to pluck from.

“I think the nostalgia for brutalism is about nostalgia for something that I don’t think we’d recognize if it returned,” said Michael Abrahamson, a PhD candidate at the University of Michigan, and founder of the Tumblr site Fuck Yeah Brutalism, which now has 220,000 followers. “It’s nostalgia for an optimism that a lot of these buildings embody. Really, it’s the optimism of our parents’ parents. It’s a sort of a belief in the future.”

In England, for example, there was a belief that brutalist housing estates would completely restructure the lives of the poor, Abrahamson said. “I just don’t think we have that kind of belief in architecture, or in the future, any more.”

The bottom line: Concrete has become a cipher for capitalism. It’s the second-most consumed product on Earth after water, and we make three tons of the stuff each year for every person on the planet.

If you grew up in a city of moderate size, anywhere, then you probably grew up near an example of brutalism, because the style dominated public spaces in the second half of the 20th century. Brutalist buildings started popping up everywhere across the world in the early 1950s, and reached their peak between 1964 and 1966, with the overwhelming number being used for educational facilities, then housing, offices, churches, libraries, government buildings, and museums. One in every five professional-architecture degrees in the United States is now earned, themselves, in brutalist buildings, including those from Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and here at UC Berkeley.

[pullquote-1] Aside from a sort of “know it when you see it” quality, it’s not always deadly straightforward to define a building as brutalist, which leads to a bit of sniping amongst the more rabid fanboys in the architectural community. (Anybody who comments on this article saying some of our chosen buildings aren’t strictly brutalist will be executed.)

The utterly datable — as in, we’d like to take it out for some nice potatoes, maybe a glass of wine — Transamerica Pyramid in downtown San Francisco, for example, is built with concrete, but it technically qualifies as “futurist” in style. To help mitigate this kind of fanboy confusion, the architect Dana Buntrock created a humorous checklist back in 2013 for building owners trying to decide whether or not their buildings were brutalist. It includes questions such as, “Has the building’s uncompromising character made it hard to add on to?” and, “Is the building ‘an acquired taste?’” or, “Does it have a zealous fan club?” and even, “Has it been used as a setting for a dystopian or science fiction film or television series?”

While buildings of other styles have had their moments, brutalist buildings — in part because of the material with which they are constructed, but also because they tend to be functional spaces and often are regarded as “ugly” — tend to have been more overlooked by academics in the architectural field until recently.

Brutalism in The Bay

The story of brutalist architecture in the Bay Area is similar to the stories of urban renewal in lots of cities across the United States in the 1960s, when transit and highway projects, and huge institutional and government buildings were placed in places that urban planners perceived to be declining.“And that’s the primary failing of architecture in the U.S. during that time period,” said Abrahamson. “It’s the inability to see cities as something other than a development opportunity. A building as something other that what you pass by on your way to work.”

In downtown Oakland, the Oakland Museum of California is a prime example of brutalist architecture, according to its director, Lori Fogarty, who points out that The New York Times called it “one of the most important buildings of the century” when it was opened in 1969. The building’s architect, Kevin Roche, even won the competition to design it after his own boss, Eero Sarinen, died suddenly of a brain tumor. Which sounds brutal.

Roche’s vision was certainly bold for the time. “Roche’s whole vision for the museum was that it would be a garden for the people of Oakland,” said architecture critic Andre Ptazynski, who isn’t sold on the idea that the museum is “brutal,” but rather thinks of the museum as “noble” and “heroic.”

“He wanted all four sides of the building to be open to the public, and for admission to be free. For people to go in at any time, wander in and out of the galleries and for the building to be truly permeable,” Ptazynski explained. “He didn’t go with an existing model of a museum. He looked at Oakland, saw the post-war white flight and asked himself, ‘What does this city really need?’ He wanted to give the citizens a positive experience of living in the city. What a noble idea.”

The museum began charging for admission in the 1980s, albeit continuing to offer incentives such as a “pay what you can” day on the first Sunday of each month, half-price admission on Fridays, free admission for people under 18, and incentives for seniors.

The museum’s current director, Fogarty, says there are aspects of the museum’s design that work really well, and others that don’t work so well. “What we’re trying to do is fulfil Kevin Roche’s original vision of what a museum is supposed to be,” she said. “But there are challenges. There’s a brutality to it, and the outside walls can sometimes feel like a fortress.

“We always talk about this moment of revelation: the huge community celebration when the Golden State Warriors won the [National Basketball Association] championship in 2015, and the huge community celebration was right next to us, and we were literally invisible. We want to extend the welcome to everyone, and 12-foot concrete walls don’t really do that!”

As a result, the museum is in preliminary conversations with the Oakland-based landscape architect Walter Hood to look at ways of making the walls more “porous,” Fogarty said. We asked for some pictures of Hood’s so-called improvements, and we’ll see what he comes up with.

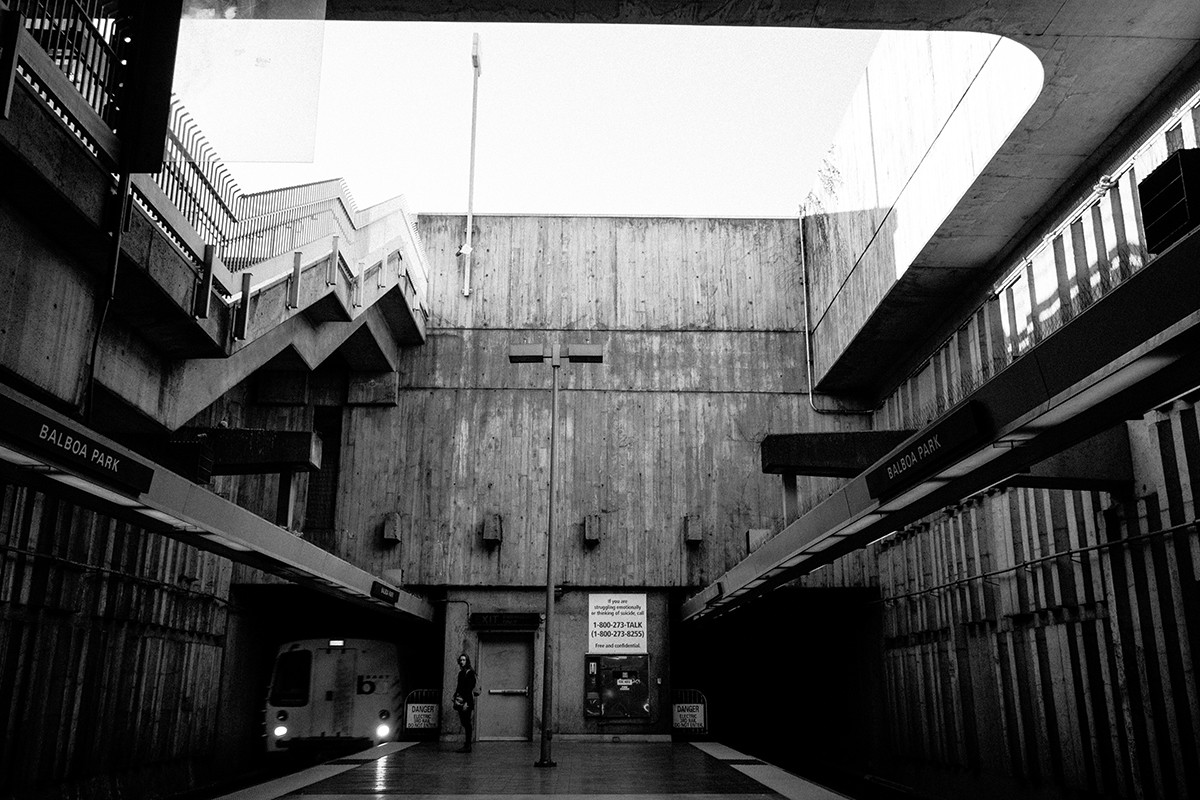

In West Oakland, the United States Postal Service Sorting Center is a debatable example of brutalist architecture. But there is no doubt whatsoever about the brutalist status of the West Oakland BART station.

“Unfortunately, when the city took over ten blocks of real estate in West Oakland, sending in military tanks to demolish all of these African-American houses, they were sending a message to the Black community, saying ‘This is what we think of you,’” explained Saturu Ned, a member of the Black Panther Party in the 1960s, which would later have its headquarters on Peralta Street, a few blocks north of the post office site. Ned, who went by a different name at the time, remembers learning to shoot in an underground rifle range on the block.

“Brutalism as a form of architecture may have aroused some hipster nostalgia,” Ned said. “But it’s important to remember that an element of that nostalgia is racist.”

Fair point. Not all architecture is perfect. And brutalism’s arrival in West Oakland embodied horrendous errors. The BART line on Seventh Avenue, for example, runs right through what was once a thriving Black entertainment district, and Ned still runs restorative-justice tours through the neighborhood for those interested in finding out more.

“The important thing is that these things aren’t forgotten,” Ned says. “And that the people who live in Oakland now understand the history of what happened here. If you’re not aware, then you’re not able to correct the situation. People need to understand what happened in West Oakland so that they can change the way things happen in the future.”

As white, hipster residents of West Oakland, frankly, we couldn’t agree more.

The design of the BART stations was influenced by space exploration, and the aerospace industry, according to Sy Adler, a professor of urban planning at Portland State University, who wrote his doctoral thesis on BART at Berkeley during the 1970s.

“A popular framing of the traffic-congestion issue at the time was, ‘If we can put someone on the moon, we ought to be able to get someone across town in a much more timely fashion,’” he explained

In 2017, many brutalist buildings are reaching the end of their natural lives, and several of them are in need of regeneration or repurposing. Some aren’t even seismically stable enough to walk around in.

[pullquote-2] Acoustician Zackery Belanger heard about the imminent closure of the Mario Ciampi-designed, former Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive building on Bancroft Way in 2014. He and performance artist Jacqueline Kiyomi Gordon decided to go into the building and record its data for a tribute, called “Acoustic Deconstruction,” to be staged in San Francisco. An album of tributes to the building using the data Belanger and Gordon recorded is forthcoming, and you can listen to the original tribute performance on SoundCloud — if you think you can handle it.

Being inside was wonderful, Belanger said. “It’s a very unique space. Brutalist architecture, because it’s made of concrete, is very good at reflecting sound.”

UC Berkeley is taking proposals for the repurposing of the building, and has had a few, according to a spokesperson, who didn’t want to say more.

We propose that they turn it into a temple.

Fruitvale BART Station: Fruitvale station has a very space-age feel with its windowed awnings hanging above the platforms. (Architect: unknown; Construction: late 1960s.) Credits: Photo by Jung Fitzpatrick

Newman Hall Holy-Spirit Parish: Catholicism is known for its grandeur and showiness. Newman Hall in Berkeley uses its impressive size and raw walls to put the fear of God back into you. A return to awe, to stone, to a humble feeling of smallness in the face of the holy unknown. (Architect: Mario J. Ciampi; Construction: 1967.) Credits: Photo by Jung Fitzpatrick

Credits: Photo by Jung Fitzpatrick

Pacific Film Archive Theater: Abandoned, locked up, fenced-in like a wild horse, the seismically unstable theater in Berkeley is now covered in weeds and graffiti. Don’t let that discourage you, however. Even shadowed by buildings across the street and obscured from public entry, this concrete chamber can still chill your heart with its stark exterior, stacked like concrete playing blocks. (Architect: Mario J. Ciampi; Construction: 1970.) Credits: Photo by Jung Fitzpatrick