The latest changeover happened this past November, when former OUSD Superintendent Antwan Wilson unexpectedly announced his resignation to take a new position as chancellor of Washington, D.C., public schools.

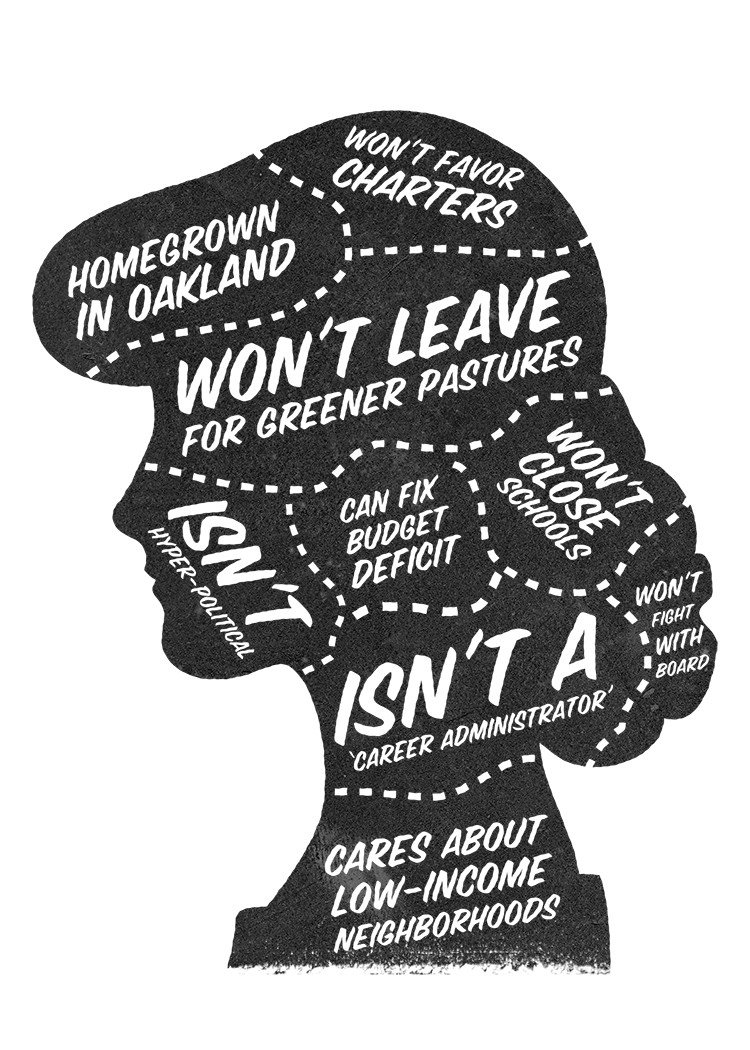

With another superintendent out, OUSD is once again on the hunt for a new leader — and many parents and vocal members of the community are determined to ensure the next face of the district is homegrown.

“I don’t think that’s too much to ask, someone who’s going to stay for 10-plus years, to finish their work,” Manigo told the Express.

Manigo is executive director of the Bay Area Parent Leadership Action Network, and she’s also one of the parents behind a recent effort to hire a superintendent that will stay long-term, a coalition called Justice for Oakland Students.

Many of those in the coalition, as well as school leaders, educators and other organizations, believe that someone from Oakland who is familiar with the city’s landscape, players, and issues is best-suited to tackle the district’s myriad problems, and will more likely be in it for the long haul.

Ten years may be optimistic. But it’s no secret that parents and teachers feel burned. Wilson left OUSD at a difficult time, with the district exploring a possible consolidation of schools, and tackling a $14 million budget shortfall. It’s also experiencing unforeseen under-enrollment, which cuts away at public funding and worsens the budget situation.

The search for a new supe is also unduly influenced by the ever-contentious charter-versus-public school debate, what with Oakland’s high number of charter locations, which some educators and parents-turned-advocates believe suck students and resources from public schools.

Kim Davis, longtime member of Parents United for Public Schools, said she’s seen what happens when a leadership position functions as a revolving door: programs are started, funding is secured, parents and teachers become invested — and then, when someone leaves and the next superintendent arrives, the new ideas don’t align with the existing agenda, so programs are shuttered and left to collect dust.

“Continuing things that are working for kids, and not changing course, is incredibly essential,” agreed Preston Thomas, superintendent of OUSD’s High School Network.

Principals the Express spoke to for this story also noted that superintendents unfamiliar with the area come in with strong visions, but don’t have the context to navigate Oakland’s complexity: the district’s diversity, the city’s history, the way it’s gentrifying.

Skyline High School co-principal Nancy Bloom argued that the biggest impact of the superintendent changeover is a lack of stability in the district, and that leadership turnover doesn’t build real cohesion.

“It’s kind of like if mom or dad walks away from the family,” Bloom explained. “It feels like you’re being abandoned. ‘Why should I stay here if everybody’s bailing?’”

“People want to work where you know what to expect and where you fit in this hierarchy of things,” she said.

During the past twenty years, only two out of seven superintendents had prior OUSD experience (not including interim supes), according to an analysis by Carrie Chan, at Oakland nonprofit Educate 78.

But school board member Roseann Torres noted that “local” means something different to everyone, and she said she wants candidates from a broader sweep than just Oakland, such as throughout Northern California.

Torres also thinks the ideal candidate needs to have previous experience as a superintendent, to “fly this jumbo jet that is OUSD,” in addition to familiarity with the unique way the state conducts budgeting. Narrowing the pool to just Oakland is shortsighted, she argued.

Chan’s analysis also pointed out that, if past Oakland trends are any indication, hiring locally still will not ensure that someone sticks around — though she does not discount other benefits of familiarity with the district.

Nevertheless, the community is organizing to push for a local candidate. Last month, on February 11, about 150 people congregated inside McClymonds High School cafeteria in West Oakland for a town hall.

This was a chance for school-board members to gather community feedback for the superintendent search. They sat at different tables to hear more about the qualities or skills that the community wants from its next OUSD leader. The school board hired a firm, Leadership Associates, to pull together a profile based on the input from town-hall meetings and an online survey.

One of the foremost goals, according to Davis, is for the next supe to be able to improve education outcomes for low-income students and students of color. Charter schools, with more autonomy, tend to snatch up higher-performing students, leaving behind kids with special needs, and putting a disproportionate resource burden on traditional public schools, according to Bloom.

This was a prevailing sentiment among those who attended the town hall, explained school board member Jumoke Hinton-Hodge.

“For me, it was again kind of the classic group of highly engaged, highly entitled parents that are involved,” Hinton-Hodge said. These voices tend to put forth the same message, she argued: They want someone local, and they are usually anti-charter.

But Hinton-Hodge says these voices are not representative of all parents. She explained that many parents have children in charter schools as well as traditional public schools, and that they would not support shutting down charters or dramatically altering charter policy.

Hinton-Hodge said there is a way to talk about improving oversight of charters without being completely anti-charter. But some see charter schools very existence as damaging to children’s education and traditional public schools.

Torres told the Express that she doesn’t think the anti-charter voices should be shrugged off by OUSD. She noted that it’s common to hear of teachers at charter schools getting laid off in the middle of the school year, or of classes that collapse and result in the same teacher instructing, say, third and fourth graders in the same room.

“We hear these stories, and of course we’re worried,” Torres said.

Wilson was the second permanent superintendent appointed by OUSD after it regained financial control of the district on the heels of a massive accounting error, discovered in 2003, wherein the district was found to be short tens of millions of dollars, and the state took charge of its finances and administration.

Previously, the state appointed superintendent after superintendent, each only staying only two or three years. The state takeover did not do a quick and sound job shoring up the district’s finances, either. A 2007-08 Alameda County Civil grand jury report wrote that the district was “hampered by continuous staff turnover, particularly in the area of finance, numerous reorganizations and a succession of state administrators.”

It is well-documented that many of these state-appointed superintendents were career administrators coming from outside the region, trained by the Broad Academy, which is funded by Eli Broad, a pro-charter school billionaire and educational philanthropist. Wilson was a graduate of the academy, and the number of charter schools in the district blossomed under him and other likeminded leaders.

So far, the board has arrived at some consensus, agreeing that a candidate who is local might be more likely to stick around longer than just two or three years, the national average for large urban school superintendents. These high turnover rates don’t bode well for success in any district, Hinton-Hodge said.

The school board has compiled a shortlist of candidates they believe fit the criteria the community has put forth. These individuals were contacted to apply, and, in mid-March, the school board will start interviews, with the goal to wrap up in April.

The next step for advocates is to acquire the entire list of candidates, says Noni Sessions, a spokesperson for the State of Black Oakland, an organization that aims to channel the voice of local Black leaders. Oftentimes, the candidates who would best serve the Black community’s needs are passed over, she said, especially when private firms are hired to steer leadership searches.

“We want to be part of clarifying who should and shouldn’t be weeded out,” Sessions said.

Manigo hopes this hiring process will succeed where others failed. She shared a simple analogy for the whole situation: It’s like OUSD has walked down the same street and fallen into the same pothole over and over. And now, students are falling through, too.

“We want a superintendent … who’s like, ‘There’s a hole in this street, and I’m going to fix it, and I’m going to work with community,” Manigo said. l

Suhauna is a UC Berkeley undergraduate who previously worked as an editor, news reporter, and layout designer at The Daily Californian.

In a previous version of this story, Nancy Bloom was incorrectly identified as principal of Montclair Elementary School; she’s now at Skyline High School.