In 2005, Andy Warner took a study-abroad semester from Cornell University and traveled to Beirut, Lebanon. His plan was to study Arabic literature, explore a rich and unfamiliar culture, and meet new people.

What he didn’t plan was being caught in the middle of a revolution. Or to begin to lose his mind.

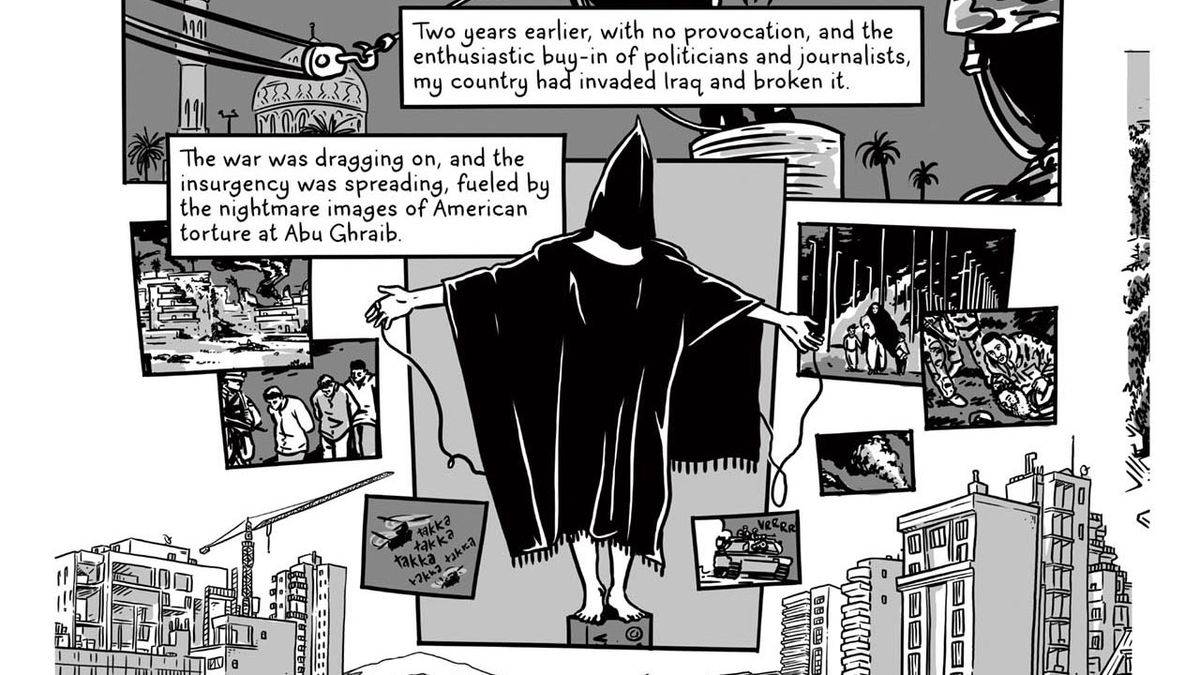

That’s the story the Berkeley resident tells in his new book, Spring Rain: A Graphic Memoir of Love, Madness and Revolutions. Warner looks back across a decade and a half of adulthood to reckon with the person he was at age 21. He recalls his quickly regretted break-up with his girlfriend, his introduction to a new social scene of LGBT students in Beirut, and the sudden outbreak of violence that may have helped tip him into mental illness.

Born in Santa Barbara, Warner enjoyed a peripatetic early childhood that took the family to Panama, Japan, Corsica, and Oxford. His father, a marine biologist, studied the hermaphroditic bluehead wrasse, and Warner and his siblings often spent the school year in California and summer in a locale suitable for his father’s research.

He gained his appreciation for comics to his mother’s insistence that he learn a foreign language.

“She started teaching us all French,” Warner said in a telephone interview. “And the way that she did that was using French comics — Asterix and Tintin and Lucky Luke. All these really amazing, big, album-sized [comic] books were constantly around our house. We would read them in the mornings with her before we went to school.”

When he set off on his own for a study-abroad program in Lebanon, Warner was no tenderfoot. He loved Beirut from the start, reveling in its beaches, nightclubs, and museums. But as Spring Rain opens, the younger version of Warner seems out of sorts.

He leaves his student housing because he suspects his roommate is reading his diary, and finds an apartment of his own, across the hall from a gay couple, Jason and Sami. Warner also socializes with Lili and Mina, fellow study-abroad students enjoying seemingly endless parties and a steady flow of alcohol, hashish, and speed. Everything goes well until Rafik Hariri, the two-time prime minister of Lebanon, is killed in an explosion. Soon the streets are full of demonstrators and cars with blaring loudspeakers. Helicopters hover overhead at all hours of the night. Warner believes that he’s being followed and experiences nightmares of self-mutilation. As the call for revolution amplifies, Warner indulges in more dangerously self-destructive behavior.

In Spring Rain, Warner’s black-and-white illustrations capture both the ancient beauty and cosmopolitan energy of Lebanon. His strengths as a writer and an illustrator complement each other, moving from detailed realism to the creepily bizarre.

Originally considering an academic career, Warner eventually decided to pursue an MFA at the Center for Cartoon Studies in Vermont.

Warner’s non-fiction comics have been published by Slate, American Public Radio and the United Nations. He is a contributing editor for the political cartooning website The Nib. His comics collection Brief Histories of Everyday Objects was a New York Times best-seller and tells the origin stories of familiar items that enhance our daily lives without receiving much notice.

Warner keeps a file of articles gleaned from periodicals, television, and podcasts, hoping that the selections will coalesce into another compendium of what he calls “oddball history.”

A case in point is This Land Is My Land, co-written with Sofie Louise Dam, which collects the stories of 30 self-made places around the world built, according to press materials, “with a dream of utopia, whether a safe haven, an inspiring structure, or a better-run country.” The book explores the world’s “micronations,” tiny countries where small groups of like-minded people settle to live in supposed harmony and issue indicia of sovereignty such as coins, stamps and flags.

“We did a really quick online version and forgot about it,” Warner said. “Three or four months later some editors got hold of it and asked us if we wanted to expand it. I’d been collecting stories about utopias forever, so it was great to off-load that particular bundle.”

Warner points to Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home and Footnotes in Gaza by Joe Sacco as the kinds of graphic non-fiction that inspires him. He said, “Comics are in this amazing Golden Age where I can’t help but be inspired by my peers around me.”

Warner admits to some trepidation at putting himself front and center in a comic that includes sex, drugs, and mental illness.

“It’s intimidating to talk about personal stuff,” he said. “But I got the opportunity to do it, and that’s an incredible privilege.”

Warner has traveled to the Middle East many times since 2005. He notes that visiting Beirut isn’t easy.

“One thing that is scary in Lebanon is how close to the surface political violence often is,” he said. “Their politicians suck. A lot of them are former warlords and oligarchs. It’s not a great group. But that’s a dangerous job. They’re always getting assassinated. Civil leaders are assassinated. Journalists are assassinated. Not enough that the country collapses under it, but it happens.”

Nevertheless, Warner says he enjoys returning to Beirut and experiencing the social fluidity that greets people there.

“Sometimes it’s hard to bridge that gap between the foreign community and the local community. But that gap is just so much easier to jump in Lebanon.”

Lebanon is back in the news, with protesters facing off against the current corrupt government.

“Revolutions and revolutionary movements come in cycles,” Warner said. “This part of the world is very connected. It’s got a ton of people talking on social media, and revolution is contagious. The last two didn’t turn out great. But I can’t help but hope for this one.”

Although not really in touch with acquaintances from 2005, Warner stays connected with friends he made in later visits to Beirut.

“Some of my very best friends in the world still live in Beirut. Cartoonists, amazing people, and they’re out in the streets today. And I can do nothing. Except express my solidarity with them and, with my whole heart, wish I was there.”