Halfway through Mimi Pond’s new graphic novel, The Customer is Always Wrong, Madge, the novel’s protagonist, is driving through East Oakland when a mysterious figure crosses the street. As described in the panel, “she’s black but wears thick white pancake makeup, opera-length white gloves, and a long, white, flowing gown.” Known as “The White Lady of 14th Street,” she’s long been a rumor around Oakland, but this is the first time Madge has actually seen her in the flesh.

Soon she scurries off, and the character drives away, hoping she’s a sign of good luck to come.

The Customer is Always Wrong is a work haunted by these spectral presences. Some are specific to Pond’s own life in the 1970s — Lazlo, Madge’s boss, is based on an old friend — but others are relatable to anyone who’s seen Oakland’s quick transformation over the years. The street grid is the same, and the BART trains still whir in the fog, but the ghost that looms throughout Pond’s novel is that of “Old Oakland.”

“I miss that it was a cheap enough place to live that people could more easily exercise their essentially Oaklandish eccentricities,” Pond wrote to me in an email. “I miss the kind of secret, hidden wonder of it that only those of us who chose to really see it appreciated.”

Pond’s story revolves around a group of artistically inclined restaurant workers in their 20s and 30s, and largely set in the diner they hover around: the Imperial Cafe, a thinly veiled stand-in for Mama’s Royal Cafe on Broadway, where Pond used to work; her previous novel, 2014’s Over Easy, was also set there. In between shifts and shitty customers, the employees work on their true passions: Madge is a fledgling artist, Lazlo is a writer, others dabble in the drug trade.

Like her fictionalized doppelgänger, Pond moved away from Oakland in the late ’70s, first to New York, and then to Los Angeles. In the ’80s, she worked for National Lampoon and the Village Voice before moving on to work for The Simpsons (she penned the series’ first full-length episode), Designing Women, and, along with her husband, artist and puppeteer Wayne White, on the beloved Pee-wee’s Playhouse.

But there was always something about that particular gig, during that particular era of Oakland, that stuck with Pond. “[Mama’s Royal] was a magnet for people who dared to express themselves creatively on the job,” she wrote. “You were a restaurant worker, but it didn’t mean you had to lose your identity as an artist and as someone with opinions and observations. I think my experience there galvanized me as an artist.”

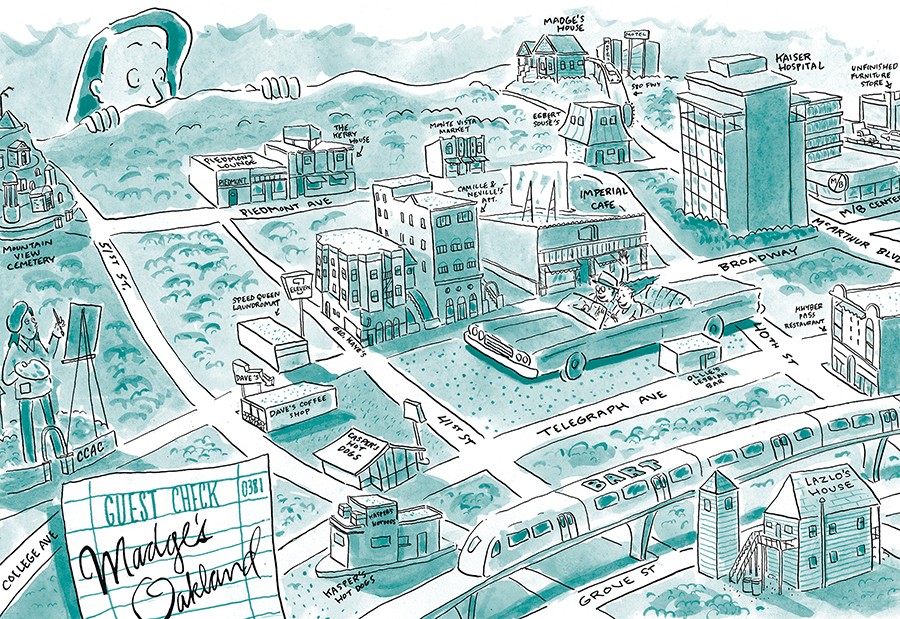

Pond still visits Oakland from time to time, sometimes to chat with old friends, sometimes to snap a few reference photos. These visits have resulted in such honed details of the town in the past — the front and back inside covers contain gorgeous maps highlighting the vistas and buildings most important to the novel’s two main characters — that it doubles as a time capsule for us readers, 40 years later, trying to decipher what life was like before “the change.”

Geo Kaye’s, the dive on Broadway and 41st, was still there. And so was Merchant’s Saloon, albeit, as depicted in Pond’s novel, much more terrifying. And of course, there was the slanted Heinold’s First and Last Chance. But the other dives and speakeasies where the characters fret over their crises, existential or otherwise, are missing from our current Google maps, either torn down or converted into ten-buck-cocktail joints. Pond’s Oakland was rougher around the edges, but it was also affordable.

Even Mama’s Royal itself, holding down the fort since 1974, is near change. George Marino, its longtime owner, put the cafe up for sale last July. While he contends he’ll only sell to someone who wants to maintain Mama’s vibe as a breakfast spot and community hub, the future of the restaurant is uncertain. (Pond’s wish is, simply, “keep everything the same, except spruce it up a bit.”)

The only constant is change. And maybe that’s the point of the White Lady of 14th Street, who Pond insists was based on a real person.

When the White Lady shows up again at the novel’s end, the characters have undergone dramatic changes. Madge’s co-workers have come and gone, sometimes via firing, sometimes the grave, and Madge herself is headed across the country to pursue her artistic dreams. But then there’s that old woman again, retracing the same old paths in her caked-on makeup.

“She’s been around as long as I can remember,” says one of the Madge’s friends, “like a ghost.”

On the longest timeline, all that’s left are ghosts anyway. So, enjoy those dive bars while you can.