Maria Luisa Contreras has worked at Prudential Overall Supply’s laundry facility in Milpitas for more than nine years, but didn’t learn that she wasn’t receiving adequate compensation for her work until last fall. “I couldn’t believe it,” said Contreras, through a translator. “I was saddened that a company like Prudential with such a solid reputation would do that to its workers.”

For the past three years, Oakland has contracted with Prudential to provide clean and pressed uniforms for its meter maids, park rangers, trash collectors, and other city employees. City administrators were just as surprised as Contreras to learn last July that the company had been underpaying its employees the whole time.

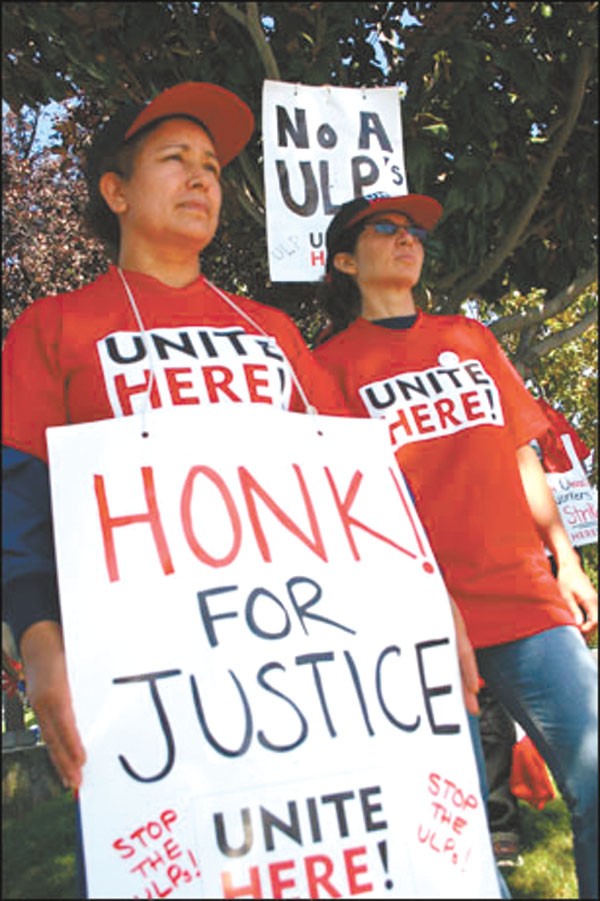

With the help of labor union Unite Here and the city of Oakland, Contreras and a group of workers filed a complaint with Prudential and reached a settlement in April that forced the company to pay more than $120,000 in back wages — both from failing to pay minimum compensation and adequate health benefits — owed to 50 to 60 workers according to Oakland’s Living Wage Ordinance. The ordinance, which was approved in 1998, currently requires any company contracted with the city for $25,000 or more to pay their employees $10.39 per hour with health benefits and $11.95 without. Federal minimum wage is $5.85 per hour, and will increase to $6.55 per hour this July.

Contreras expects to receive around $5,000 in back wages from Prudential. Although she’s happy with the win, Contreras says that the settlement is disappointing considering the extent of Prudential’s negligence. “According to the company’s records, and the explanation that the company gave us, I feel that the payment could have been more,” she said.

As it turns out, the city of Oakland also may have gotten the short end of the stick. In addition to making a non-compliant company pay back wages to its employees, the rules and regulations of the Living Wage Ordinance also give the city the right to penalize a company $500 per week per employee not adequately compensated, plus another $500 per week for not providing adequate payroll and benefits records.

The city’s investigation into the Prudential case revealed that these penalties would add up to roughly $4 million. But it was $4 million that the city would never see. The city agreed to not pursue penalties and fines against Prudential as long as the company agreed to pay the back wages in a timely manner.

“Prudential paid the employees in a sufficient time upon notification of the non-compliance,” wrote Michael Hunt, a spokesman for Mayor Ron Dellums, in a recent e-mail exchange. “They cooperated fully. Had the non-compliance continued and no resolution been imminent, the City would have pursued penalties and fines.”

But critics claim that a company like Prudential Overall Supply doesn’t deserve any breaks after violating the law for so long. According to an investigation by Oakland’s contract compliance division, the company was never operating in compliance with the Living Wage Ordinance since it first contracted with the city in 2005.

Jen Kern, director of the Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now’s Living Wage Resource Center based in Washington DC says that cities should absolutely be imposing penalty fines on companies that don’t comply with the Living Wage Ordinance. “It’s law, it’s on the books, it makes total sense, and it’s just the right thing to do,” said Kern. “The alternative is that these cities are subsidizing poverty.”

Kern says that, despite its paltry number of investigations, Oakland is actually one of the more responsible cities when it comes to enforcing its Living Wage law. “Most cities don’t have any effective enforcement,” Kern said. “They just don’t have someone on staff to do site visits and compliance reviews.”

Oakland could benefit from stricter enforcement of its Living Wage Ordinance, but has few resources available to do so, says Jason Oringer, research coordinator for Unite Here. Ironically, if Oakland followed through more on its penalities, it might have those resources. “Oakland could certainly use $4 million,” he said.

But city attorney spokesman Alex Katz says that suing a non-compliant company for $4 million isn’t as easy as it sounds — especially for Oakland. “Hypothetically, if we tried to sue this company, it could take years to resolve. In the meantime, you have to weigh the amount of taxpayer money and energy that you would need to make the case,” said Katz. “You can’t just see it as the city’s failing to pursue money that it could otherwise have in its pocket.”

In the past decade, the city of Oakland has signed hundreds, if not thousands, of contracts that fell under the living wage law. But Oakland has reviewed only 142 of those contracts for compliance. Of those, two companies were in found to be in violation of the law: Prudential and ABC Security Service, a politically connected Oakland company that provides private security guards for City Hall and the Port of Oakland. Hunt says that Oakland’s Contract Compliance Division is also currently investigating a potential non-compliance on the Montclair Golf Course.

Legally, according to Doryanna Moreno, a supervising attorney in the City Attorney’s Office, Oakland can impose fines on a non-compliant company from the time they find that the company is violating the law. Oakland has not chosen to access penalties on either company it has found in non-compliance because, “both firms cooperated fully and promptly made the employees whole. And also because it was a way of getting the workers paid and avoid litigation,” wrote Hunt.

However, it’s unclear how many city contractors routinely pay less than the living wage, because the city doesn’t have the staff or resources to investigate contractors’ compliance with the law. It’s also unclear whether contractors have been able to underbid their competitors, and thus win contracts, because they pay less than the living wage, and have no fear that the city will ever catch them. And even if it does, it won’t force them to pay penalties because of its aversion to litigation.

But that’s a stark contrast to other cities. San Diego is currently in the midst of filing a lawsuit against Prudential to collect penalty fees in addition to back wages and attorney’s fees for violations of its labor laws. In addition, Donna Levitt, division manager for San Francisco’s Office of Labor Standards Enforcement, says that San Francisco has collected more than $2 million from enforcing penalty fees for companies violating the city’s Health Care Accountability Ordinance, which is part of its living wage ordinance. “The goal is to encourage companies contracted with the city to provide adequate health care benefits to their employees or pay a fee to contribute to public healthcare,” said Levitt. She added that her office recently investigated five car-rental companies contracted with the San Francisco airport, and found that every single company violated the city’s health care and living wage ordinances.

But San Francisco’s Office of Labor Standards Enforcement has a staff of fifteen — enough resources to actively investigate companies that they suspect might be in non-compliance with the city’s labor laws. Still, Levitt said, it would be impossible for them to oversee every single city contractor, of which there are more than 1,000. “We tend to investigate those companies that we think are most likely to have low-wage employees, and are more likely to be in violation of the law,” she said.

Rich Waller, a supervising compliance officer in the department, says that they have investigated roughly three hundred cases since the ordinance passed in 2000. “All of them haven’t resulted in adverse findings, but many have,” he said.

Although it might be virtually impossible for cities with few resources to oversee all of their contractors, Josie Camacho, Oakland’s director of Constituent Services, says that the Prudential case was eye-opening. “Based on this experience, it did register that we do need a better way to monitor the city’s various contracts,” she said.

Oakland doesn’t have an office specifically devoted to enforcing its Living Wage Ordinance, but instead depends on the city’s Contract Compliance and Employment Services Division. Like many other cities, Oakland has few resources to devote to active investigations — which might include regularly checking payroll records for city contractors — and relies mainly on employee complaints to initiate investigations.

Penalties are written into the policies of the Living Wage Ordinance to give it teeth — but teeth that aren’t necessarily intended to bite, says Jennifer Lin, research director for the East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy. “From our standpoint, the penalties are a means to an end,” said Lin. “Oakland shouldn’t be relying on collecting penalty fees to support its infrastructure anyhow because it’s not a sustainable source of income.”

Lin considers it a pretty good outcome if workers receive back wages and the company pays for the investigation. Living Wage Ordinance cases often don’t make it to court, she says, because cities don’t have enough resources to pour time and money into costly lawsuits, and also are wary of being sued. Still, she concedes, cities should go after penalties whenever they can.