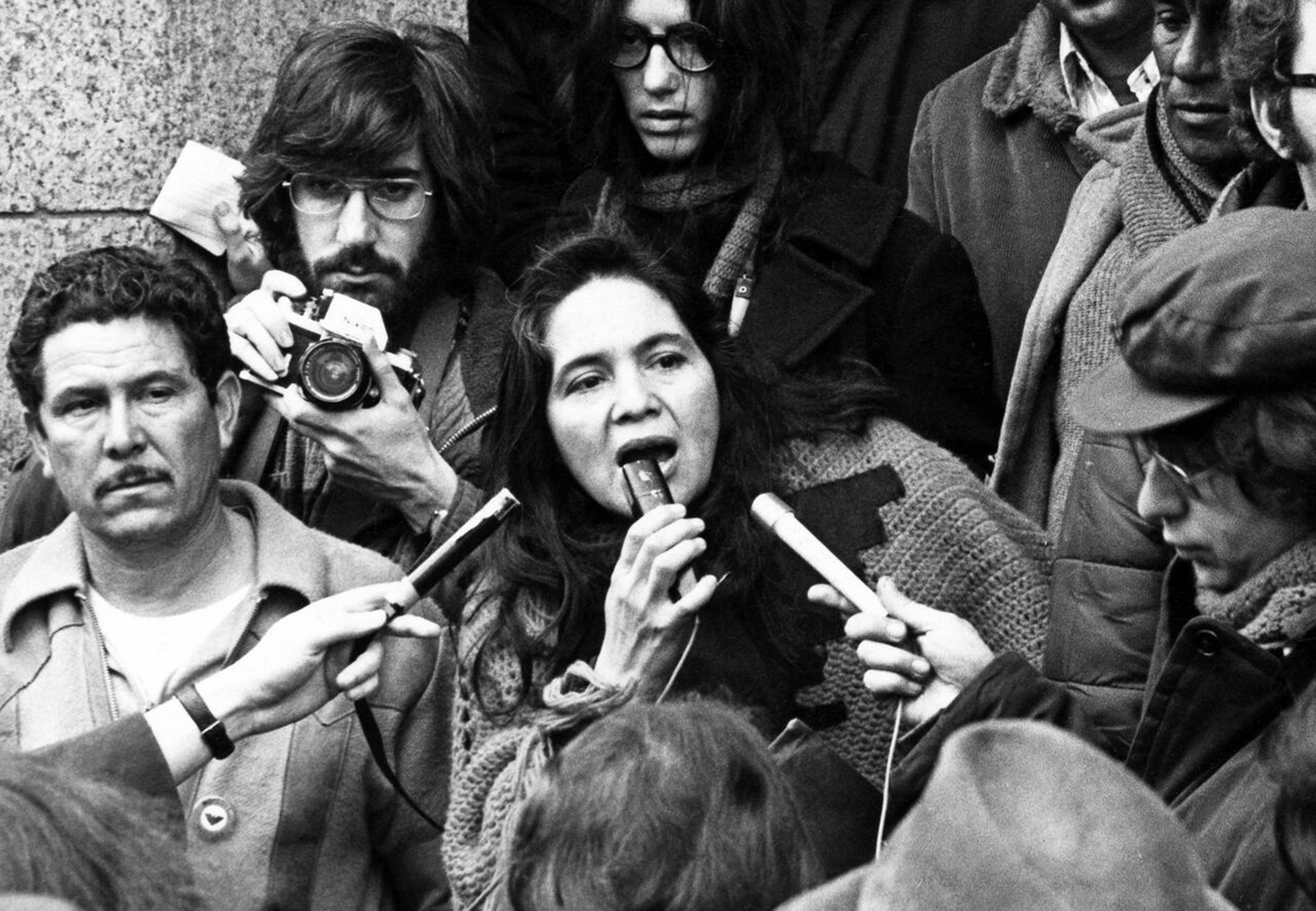

Here’s a quiz for politically aware readers: Which nationally known labor leader was arguably the first to fight what has been called “the feudal wage slavery of agribusiness” as well as ingrained racism and police brutality directed toward California farmworkers, at great personal risk to herself? Hint: She led a grape boycott, inspired a generation of laborers, and helped open up the labor movement to women — yet even now her achievements tend to be covered up in history books. Another hint: She was usually pictured standing behind farmworkers’ hero Cesar Chavez. Answer: Dolores Huerta, subject of the eye-opening documentary Dolores.

The fact-filled and emotionally moving biodoc by San Francisco filmmaker Peter Bratt (La Mission) has quite a story to tell about Huerta. Born in New Mexico and raised in a family of field workers in Stockton, Huerta came of age in the San Joaquin Valley in the 1940s. Fertile as the valley was, the prospects were barren for farmworkers, in her view, not only due to the back-breaking work but also because the Spanish-speaking pickers were treated as chattel. Huerta’s resistance took the form of grassroots consensus-building and the drafting of legislation for workers’ rights, against the violent opposition of growers. Her dream: “To be accepted for what I am.”

What she was — and still is, at age 87 — evidently rankled not only powerful produce growers but rivals within her own organization. According to many of filmmaker Bratt’s talking heads — including playwright Luis Valdez, activist Angela Davis, journalist Gloria Steinem, politicians David Roberti and Art Torres, numerous labor allies, and several of Huerta’s 11 children — Huerta faced prejudice as a woman in a traditionally men’s world. Big-time union bosses didn’t seem to want her around. Evidently even her compadre Chavez initially seemed jealous of her. But she persevered.

A subject as basic as agriculture involves an array of complicated and fiercely contested related issues. In the red-hot 1960s, Huerta and the National Farmworkers Association (which she co-founded with Chavez; later renamed the United Farm Workers) made common cause with Filipino Americans, Blacks, anti-Vietnam-War groups, and Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, on such topics as civil rights, pesticides, the “economics of racism,” and, always, feminism. Farmworkers addressed the threat of chemical poisons in food before anyone else. All the while, Huerta tended her garden of social initiatives, highlighted by education, credit unions, income tax services, and a 1969 grape boycott that raised consciousness all around the world. Inspired by her leadership, the most exploited workers in the country rose up and pushed back.

Her enemies were numerous. In one especially alarming encounter in 1988, the then-58-year-old Huerta was brutally beaten by San Francisco police in front of the St. Francis Hotel while picketing President George H.W. Bush, and she nearly died. She is still being smeared by rightwing haters — a sure sign she is doing something right. Her lifetime of struggle led her at one point to reflect: “I found out that no matter what I did, I could never be an American. Never.” With all due respect, that is absolutely not the case. Dolores Huerta is the very finest kind of American, and Dolores is a rousing profile of courage.

Huerta will appear in person, Saturday, September 9, for a Q&A at the 5:20 p.m. and 7:40 p.m. shows, at Landmark’s Shattuck Cinemas in Berkeley.

Dolores

Directed by Peter Bratt. Opens Friday.