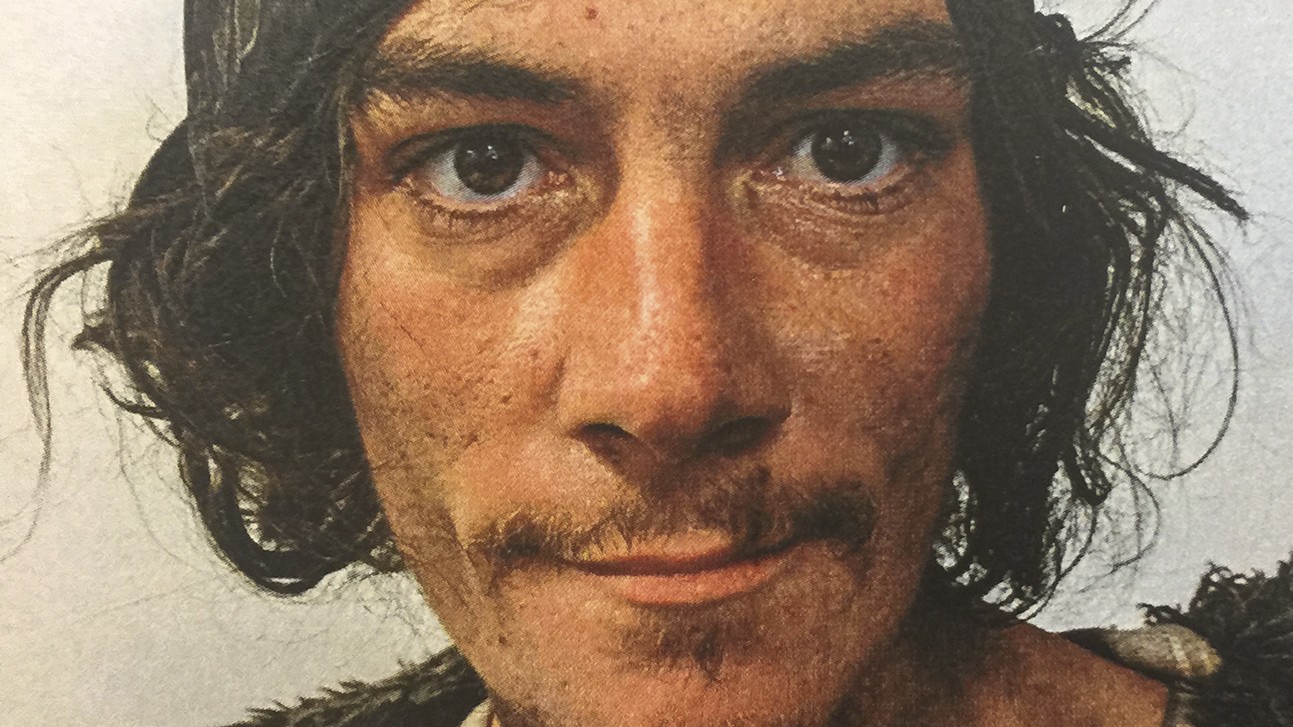

Joshua Ryan Pawlik wasn’t moving. In fact, even though he was armed with a pistol, the 31-year-old man appeared to be unconscious shortly before Oakland police officers surrounded him at gunpoint on March 11 and shot him dead in a barrage of rifle fire.

Rarely is there an officer-involved shooting these days that isn’t intensively scrutinized by the public and media. But since that day, hardly a word has been said about who Pawlik was or the events that led up to his death. The Oakland Police Department continues to withhold information about the case, including crucial police body camera video of the fatal incident.

Other than a vigil organized by his close friends, there haven’t been any protests. After his corpse was examined by the coroner, Pawlik was cremated, and the coroner’s report is being withheld from the public pending completion of OPD’s investigation.

The result is, in death, Pawlik — who spent his entire adult life on the margins, mostly homeless and suffering from schizoaffective disorder and a debilitating drug addiction — has been disappeared.

And because of where he died, in an alleyway between two houses with no one else around, there are no independent witnesses who can speak to what happened.

But the circumstances surroundings Pawlik’s death closely resemble other controversial police shootings. For years, the Oakland police and other Bay Area departments have followed an apparent policy of surrounding unconscious and sleeping people who are believed to be armed. Then, at gunpoint, the police suddenly wake them up and order them to surrender under threat of lethal force. Several of these incidents, including another recent case in Oakland, have predictably resulted in fatal shootings. Other cases have stirred controversy, leading to protests, lawsuits, and calls for change.

But, so far, not in Pawlik’s case.

“Nobody’s around to advocate for him,” one of Pawlik’s friends said in a recent interview. The woman asked not to be named because she lives on the streets of San Francisco and worries about the police targeting her for drug possession. She said the fact that Pawlik has no family in California means that no one has been able to put pressure on the police for answers. She also thinks his stigmatized identity has allowed society to more easily ignore his death.

“Even if we protested, they’d just dismiss us as a bunch of homeless drug addicts,” she said.

And some will find it easy dismiss Pawlik. Dependent on heroin, he survived by shoplifting and selling drugs in San Francisco’s Tenderloin and Civic Center, say his close friends. His nickname, “Junkie Josh,” was an affectionate jest. It was also bluntly honest.

Pawlik was reportedly carrying a pistol and a substantial amount of cocaine when the Oakland police surrounded and shot him. And then there was the money — around $110,000 — in his backpack. Rumors have circulated on the streets about why Pawlik ended up in West Oakland armed and carrying a small fortune, but the rumors conflict with the soft reputation Pawlik had among his friends.

“We never noticed any violent tendencies,” said Amber Farmer, who grew up with Pawlik in the small city of Fredericksburg, Va. “He was a free-loving hippie. Why would he have a gun?”

“He absolutely did not have a violent history,” said Chelsea Swift, a mobile crisis intervention worker who knew Pawlik. “Having a weapon, to hear that was shocking. Even the fact that he was in Oakland was shocking to me.”

While Pawlik had been arrested twice for drugs in San Francisco, he did not appear to have a history of violence, according to a search of criminal records in several counties where he lived over the past decade.

He was also penniless most of his adult life. Pawlik relied on the occasional wire transfer of $40 from his parents, or food stamps and safety-net health-care programs. For those who knew him, the gun and money are a mystery.

“The shame and stigma around drug use and being homeless is layered and intense,” said Mary Howe of the Homeless Youth Alliance, a San Francisco harm reduction organization. Howe, who personally knew Pawlik, described him as “exceptionally intelligent” but psychologically tormented. He was always trying to get better, to quit using, Howe said. “He really wanted a different life.”

[pullquote-1]“He wrote a poem when he was 16,” Kelly Pawlik, his mother, told the Express in a recent interview. “It was called ‘The People in My Head.’ I cry when I read it.”

Kelly knew more than anyone about her son’s afflictions: his emotional volatility and self-sabotaging from an early age; his chronic drug abuse; the traumatic death of his close childhood friend; his suicide attempts. Through it all, he maintained a strenuous but ultimately unsuccessful resolution to suppress his delusions. Pawlik was conscious of his mental illness, but never able to overcome its tortuous effects.

“He struggled every minute of the day to keep it at bay,” Kelly said. “He referred to it as something that held him back. ‘My cursed brain,’ he called it.”

But for all of Pawlik’s problems — his psychological torment and spiral downward into the criminalized world of addiction — his family and friends question why the Oakland police found it necessary to kill him. They wonder, couldn’t they simply have disarmed him? As with other incidents where the police have surrounded an unconscious, armed person, it’s possible that different tactics could have saved his life. This is what his mother, Kelly, wants to find out.

It was a little after 6 p.m. on March 11 when an anonymous 911 caller reported Pawlik lying on the ground between two houses near several trash bins on 40th Street in West Oakland. He appeared to be experiencing some kind of medical emergency, but the first emergency responder on the scene, an Oakland police officer, noticed a small pistol. The gun was either in Pawlik’s hands or nearby. Wherever it was, the officer retreated, called off the paramedics, and signaled for backup.

The city of Oakland declined to make fire and police reports of the incident public. But according to OPD’s only statement about the shooting — a press release issued three days after it happened — the officers who responded were “developing a plan for a peaceful resolution,” but Pawlik “did not comply with their commands during this interaction.” Pawlik presented an “immediate threat,” so they shot and killed him.

The department also disclosed the names of four officers who fired at Pawlik: Sergeant Francisco Negrete, Officer William Berger, Officer Brandon Hraiz, and Officer Craig Tanaka. And OPD released a photograph of a silver and black semi-automatic pistol that Pawlik was allegedly carrying.

A transcript of OPD’s radio records — obtained by the Express without the city’s assistance — as well as a video taken by a bystander and uploaded to Facebook, reveals a little more about what happened.

Police dispatchers told responding officers that Pawlik was carrying a firearm. He was described as “a light-skinned male wearing blue jeans, white shirt, dark jacket” and said to be “down on the ground between two houses.” The situation wasn’t initially described over the radio as a possible medical emergency.

Instead, one of the first officers on the scene communicated that it “looks like he’s under the influence of 922,” using OPD’s code for alcohol intoxication. “He has a small semi-automatic in his right hand,” said the officer.

A few minutes later, another officer on scene broadcast that Pawlik “still appears to be unresponsive and not aware of our presence.”

Officers surrounded Pawlik by taking cover behind a squad car with guns trained on him while others waited one block up on 41st Street. They anticipated he might try to escape by running through backyards and wanted to be in position to cut him off. They also blocked through traffic and evacuated people from the street.

About halfway through the incident, one of the officers observing Pawlik said over the radio, “gun just moved.” He did not say whether Pawlik had regained consciousness or how, exactly, the gun moved.

Not long after, OPD’s armored vehicle, a Lenco BearCat, arrived. The police parked the BearCat directly in front of the alleyway where Pawlik was lying. From behind its bullet-proof plates, officers trained AR-15 rifles on him. According to radio communications, at least three officers were armed with rifles.

Then, according to a cell phone video recorded by Amanda Van Raalte, a bystander who observed from one block away, the police began shouting commands at Pawlik. One officer can be heard yelling “hands up!” several times followed by “hands off the gun.”

Roughly 20 seconds later, officers Hraiz, Berger, Tanaka, and Negrete fired a fusillade at Pawlik. Then, over the radio, officers described moving in to handcuff Pawlik and search him as he lay dying on the ground.

Throughout the incident, OPD did not know who Pawlik was. In fact, they didn’t positively ID him until after he was dead.

The trash bins nearby were struck with several bullets and bullet fragments fired by the police. Pawlik’s friends who have visited the site said they observed that the entry points on the bins are higher up than the exit holes. They believe this shows the police fired down on him as he was lying on the ground.

Did Pawlik wake up? Did he know where he was and who was yelling at him? Did he aim the pistol he was carrying at the police or make some other threatening motion? Only the body camera video recorded by the officers who shot him can potentially answer these questions.

After months of requests, Pawlik’s mother, Kelly, was finally allowed to view the video last Friday. She flew to California and watched it in-person at the Police Administration Building.

Afterward, she told the Express that she agreed not to disclose any details about what the video specifically shows, but she said she now has “grave concerns” that the police wrongfully killed her son.

[pullquote-3]

From a very young age it was apparent that Pawlik’s mind couldn’t rest. Even though his elementary school teachers thought he was brilliant, he had trouble focusing. His family worried about whether he would complete high school. That’s when they discovered Pawlik was using Adderall to self-medicate. The amphetamine-like stimulant gave Pawlik a peaceful focus. But it wasn’t enough. He eventually began using opiates to treat himself.

“He expressed to me numerous times that being on drugs, heroin or whatever, it quieted the voices,” said Kelly Pawlik.

He once explained it to his mother this way: His untreated state was like a radio that’s tuned between two stations. One conversation overlapped another, cutting in and out and making it impossible to concentrate.

Pawlik quit high school when he was 16 and obtained his GED. He later began working as a summer camp counselor, but his increasing use of heroin made working around kids impossible. He took on jobs in restaurants in Fredericksburg, but he was frequently late and had trouble staying employed.

It was evident to his family and friends that his mental illness was worsening and expressing itself as schizoaffective disorder. More troubling was that his drug use was morphing from self-medication into a full-blown addiction that worsened his overall ability to cope.

It was around this time that Pawlik had an extremely manic episode and, for the first and only time in his life, he threatened his family by picking up a kitchen knife and shouting, “I’ll stab you!” Kelly and her husband, Pawlik’s stepfather, Jeff, called the police. They said it wasn’t that they felt endangered so much as they were at the end of their rope with his drug use and delusions, which had become highly disruptive to their lives. Kelly said they hoped that by putting Pawlik into the juvenile justice system the authorities might actually give him the treatment and medication he needed. Treatment was something Pawlik’s working-class parents couldn’t afford on their own.

Looking back, Kelly thinks it was a mistake to assume the police and courts could address her son’s mental health issues. Instead, the authorities branded him a potential criminal.

Adding to Pawlik’s troubles, his best friend died a couple years later. Pawlik’s family and friends believe that the tragic experience set back any chance he had of stabilizing.

It was a warm June afternoon in 2003 when Pawlik, Jeffrey Albury, and several others went down to Riverside Drive along the Rappahannock River in Fredericksburg. The Rappahannock is a popular swimming attraction, but summer rains had turned the waterway dangerous. Against others’ advice, Albury got in. He was sucked under by a strong current. Pawlik scrambled to the water’s edge and saw Albury come up once for a gasp of air, his arms desperately reaching, but he was dragged down again and pummeled by rocks. His body was found three days later far downriver.

“We definitely noticed a major, traumatic downslide after that,” Kelly said about her son. “He felt somewhat responsible. He felt he should have stopped him from going in, or jumped in after him.”

Haunted by his friend’s death, Pawlik’s mental illness become more acute. And his drug use intensified. Years dragged on and he floundered untreated like many Americans who can’t afford health care. His behavior became more erratic, and then, for the first time, he stole money — a lot of it.

In 2008, Pawlik was working at a local shopping mall when an elderly woman showed up with several thousand dollars in cash asking to purchase gift certificates. Pawlik accepted her money and, after the woman left thinking she had completed the transaction, he disappeared for several days with the cash.

Pawlik called his mother four days later, apologizing. He said he’d never seen so much money in his life and he “just flipped” and decided to use it to travel to Tennessee to visit a former girlfriend. When he returned, he was charged with larceny and ordered to pay restitution. He also stayed in jail for a short period.

As his drug use became more frequent, Pawlik moved out of his mother’s home and in with a friend nicknamed Cubby. Cubby was a heroin user who was dying from HIV and his propensity to overdose. He and Pawlik would score drugs and stay inside getting high for days. Pawlik also acted as Cubby’s caretaker. But he increasingly burned bridges, lost jobs, alienated friends, and spiraled downward.

It got to a point where he couldn’t work in the small town of Fredericksburg anymore, and after Cubby died, Pawlik had nowhere to go. He showed up one night asking to sleep on his mother’s couch, but Kelly, heartbroken, turned him away.

Desperate and without the money needed to put him in a drug and mental health treatment program, Pawlik’s family thought that getting him out of Fredericksburg might help. On July 4, 2011, they bought him a bus ticket to Albuquerque, a city that Pawlik said might be a good place to start fresh. He had some friends there, too. And his parents helped him pay for a cheap hostel for several months. He left with a tape recorder his stepfather gave him and promised to record what would become a podcast.

But it didn’t work out. Pawlik struggled in the rough, unfamiliar desert city. He couldn’t find work. He ran out of money. Briefly, he was homeless. Two male acquaintances ended up offering him housing, but they had a falling out and Pawlik left suddenly, leaving many of his belongings behind. His family believes he may have been sexually exploited. And Albuquerque wasn’t somewhere he could escape drugs. In fact, the city has been swamped with methamphetamine and heroin for decades. Pawlik tried committing suicide twice while his family agonized over what to do next.

One day, out of the blue, Pawlik called his mother and said things were going to be okay. He was on a bus heading to California. But it wasn’t a Greyhound bus; rather, it was a converted school bus, and he was riding with a motley group of people he called a “bunch of rainbows” headed to work in the cannabis fields of the Green Triangle. A few weeks later, he called again and said he was in San Francisco living with hippies and punks in Golden Gate Park.

“Josh was an original part of the SF Dogs,” said Jennifer Peterson, a friend of Pawlik’s who worked as a peer counselor for homeless youth in San Francisco.

One of several “tribes” made up of homeless and vagabond youngsters, many of them addicts and runaways, the SF Dogs bonded over music, including the Grateful Dead and reggae, and lived communally on the streets. Like generations of youngsters before them, they came to the Haight-Ashbury fleeing trauma, abusive families, and other demons. They survived through working odd jobs, panhandling, selling drugs, and sometimes doing sex work and other criminalized activities. Pawlik fit in.

“I was despondent he was living in the park,” said Kelly. “But he said, ‘Mom, I’ve never felt freer in my life.'”

In San Francisco, Pawlik gained a reputation as a generous bum and defender of the streets. He even made the news by helping organize a 2013 protest against park rangers who were accused of brutalizing homeless youth.

[pullquote-4]“I woke up to the two rangers picking me up, dumping me out of my sleeping bag onto my head, kicking me in the head,” Pawlik told KTVU.

That same year, police arrested Pawlik and charged him with felony possession of marijuana with intent to sell. Pawlik, according to his friends, was selling weed and other drugs, but it wasn’t profit-motivated so much as just a way to score his own drugs and have some extra money to spend.

Sometimes, under the trees or in a back alley, he would educate others on how to safely inject, and he would follow up with training on how to administer naloxone, which can reverse an opioid overdose.

“Josh would help people out,” said Peterson. “He would give out clean needles. He’d set someone up if they didn’t have money but were sick.”

It may not seem like altruism, but for those who know the psychological toll of addiction, Pawlik’s concern for others was at times selfless.

Another friend of Pawlik’s, who asked not to be named, said she passed out once after shooting a particularly potent dose of heroin on the sidewalk. Pawlik stayed by her side for hours, at first to make sure she hadn’t overdosed, and then to guard her belongings. “He didn’t have to,” she said. “Other people, even the people you thought were your friends who you’ve known for a long time, will take your stuff and disappear, and when you wake up you have nothing left. Not Josh.”

Through the assistance of the Homeless Youth Alliance, Pawlik eventually moved into an SRO in the Tenderloin. He attended counseling sessions and worked toward treating his mental health issues and drug addiction.

Howe of the Homeless Youth Alliance, and Chelsea Swift, another harm-reduction educator, remember how Pawlik would request that they meet for counseling sessions up the street at Ben and Jerry’s, where he’d get a pint of Chocolate Therapy ice cream or a milkshake.

But his schizophrenia undermined what fleeting forms of stability he was able to create with the help of others.

“Josh, as I knew him, was very paranoid of law enforcement,” said Swift, who became close friends with Pawlik over several years. “He is someone who, just because of his experiences and the communities that he’s involved in, he’ll have way more police attention and contacts.”

But for all his run-ins with the police, Pawlik had a thin record in San Francisco. Besides the 2013 marijuana arrest, he was only arrested and charged one other time. Late last year, he was arrested for possessing a small amount of methamphetamine — a misdemeanor at most.

“He was very aware of his place in society, as it viewed him,” said Swift. “He knew he was always on this uphill battle.”

The way that OPD treated Pawlik closely resembles another controversial officer-involved shooting that occurred in June 2015.

Demouria Hogg had inexplicably parked his car in a roadway near Lake Merritt with a pistol visible in the passenger seat. Then he fell asleep. It was 7:30 a.m. on a Saturday and police suspected the car of being linked to a burglary in San Francisco the night before. Firefighters were the first to show up, but when they saw the gun they backed away and called the police.

OPD responded by surrounding the car and training their guns on Hogg. They attempted to wake him up with sound and even beanbag rounds fired from a shotgun at the car’s windows. After about an hour of failed attempts to rouse Hogg, the police finally broke a side window and hit him with a less-lethal Taser weapon. Hogg was now awake. An officer stationed at the front of the car to provide lethal cover believed Hogg was reaching over toward the passenger seat, so she shot and killed him.

The Alameda County District Attorney’s office investigated the incident and cleared the officer of wrongdoing. OPD’s internal affairs also appears to have cleared the officer of any serious policy violations, but the department doesn’t comment on the results of its investigations.

Ultimately, the city paid $1.2 million to settle a wrongful death lawsuit filed by Hogg’s family.

A similar incident occurred in 2012 in Hayward when Mohammed Shah was sleeping in the front passenger seat of a car that had been reported stolen. A Hayward police officer noticed the car, ran its plate, and decided to wake up Shah and arrest him. According to court records, the officer banged on the car window, startling Shah out of his sleep. Shah responded by moving into the driver’s seat. The officer then proceeded to break the driver’s window and hit Shah with his palm. Finally, the officer commanded Shah to put his hands up. A witness in a park across the street saw Shah raise his hands, but then when one hand moved, the officer shot Shah several times. Later, the officer said the presence of a pocket knife somewhere in the car caused him to fear for his life, but Shah’s relatives said that the officer caused an unnecessarily disorienting and dangerous situation that could have been resolved peacefully. Attorneys for Shah’s relatives also claimed that the knife wasn’t discovered until after other officers arrived.

The killings of Hogg and Shah highlight a controversial police tactic: surrounding unconscious armed people at gunpoint, waking them up suddenly and demanding they immediately surrender, and using lethal force against them if they make any motion that could be construed as threatening.

Attorney John Burris, who represented the families of both Hogg and Shah, told the East Bay Times shortly after the Hogg case settled that, “[Hogg] had a normal reaction a person would have when they are awakened from a deep sleep.” If they wake up and find themselves in a chaotic situation where commands are being screamed at them with the threat of death imminent, they’re likely to make a mistake, or panic and make a motion that could easily be construed as a threat.

Melissa Nold, an attorney with Burris’ law firm who has been working with Palik’s mother, said Pawlik may have been killed for similarly unnecessary reasons.

“When you rouse someone, you have to expect he’s been out for maybe 45 minutes and he may not have any idea what’s going on,” said Nold. “The weapon near them doesn’t give the police the right to kill. They’re still required to comply with the laws in place about issuing warning with intent to shoot.”

[pullquote-5]It’s possible the four Oakland police officers who killed Pawlik did all they could to prevent the shooting. But it’s also possible that they escalated the situation and fired their weapons when they didn’t have to.

OPD told the Express that officers use tactics spelled out in the department’s “Barricaded Subject Incidents/Hostage Negotiation/High Risk Arrest/Warrants” training bulletin when they come upon anyone who is armed and unconscious. The department declined to say if the training bulletin specifically addresses the situation of a sleeping or unconscious person, however. OPD also declined to make public a copy of the bulletin because it discusses strategies and tactics.

Besides identifying the officers who shot Pawlik, the department hasn’t provided any further information about their roles in the incident or who else was on the scene, including their supervisors.

Two of the officers who shot Pawlik were recently sued by a Stockton resident who alleged that they racially profiled him and fabricated police reports to frame him for selling narcotics. Shelly Watkins said he was visiting Oakland to attend a Bible study two years ago when he was approached by a stranger in a West Oakland parking lot who asked for a cigarette. Watkins gave the man a smoke and some spare change. Minutes later, Watkins was pulled over while driving a couple blocks away. Officers Brandon Hraiz and William Berger arrested him and booked him into Santa Rita Jail for allegedly selling narcotics. But a search of Watkins’ car and a strip search the officers forced him to undergo at the jail failed to turn up any drugs.

Berger wrote the report recommending the district attorney charge Watkins with a felony for selling narcotics and attested that multiple OPD officers viewed a drug transaction. But the DA eventually dropped the charges for lack of evidence.

The City of Oakland paid Watkins $50,000 in July to settle the case.

It wasn’t like Pawlik to go missing for very long. Too many people on the streets of San Francisco knew him. He was a fixture in the Tenderloin, Civic Center, and the Lower Haight. When he was living on the streets, he’d camp out behind a church on Waller Street. Even when he was living in an SRO, he would be seen around the city. In the Tenderloin, he sometimes sat with friends on Larkin Street, by the Phoenix Hotel. It was a popular spot to score and shoot drugs or to just catch up on gossip.

Ironically, the district offices of the federal Drug Enforcement Administration are one block away, in the Phillip Burton Federal Building. From there, DEA agents can literally look down on the dozen or so people, mostly homeless youth, who gather in the afternoons to use heroin and crack. Every few months, the city sweeps the sidewalk clean, but the street kids always make their way back. The open-air drug markets along Turk and Eddy streets are also visible from the DEA’s perch. In the Civic Center, Pawlik would sit with friends and talk for hours. He’d sometimes be seen in the back alleys along Polk or South of Market.

People noticed when Pawlik left San Francisco sometime in mid-February. It didn’t take long for rumors to spread. Two of his friends, Jennifer and Ashley, said they heard Pawlik may have stolen the pistol he was found with out of a car. But the only use he would have had for a gun, they said, was to sell it for fast cash, and probably the best place to sell a stolen firearm was in Oakland.

Others speculated that he may have actually needed the gun for protection.

“It might have been that Josh was suspected of being involved in a big drug rip-off so he might have gotten a gun and he went to Oakland for safety,” speculated another friend who asked not to be named because she’s a drug user known to the police. “Nobody would know where to look for him in Oakland, but in San Francisco, he’d be easy to find.”

In fact, Pawlik called his mother in late February and told her he was staying in an Oakland hotel. He sounded upbeat. He’d recently come back from working at a cannabis grow. But he also mentioned that there was a “hit” out on him by a very serious group of drug dealers who controlled turf in the Tenderloin. Kelly thought her son’s warning was simply a paranoid delusion.

This was the first time Pawlik mentioned the money to her and it just didn’t seem real. He said he’d been sharing the hotel room in Oakland with another man, whom he didn’t identify, but he said this stranger left and never came back. A few days later, when Pawlik checked out of the hotel, he told his mother that he took a bag the man left behind. In it was over $110,000. Kelly thought this, too, was a delusion and dismissed it.

But Pawlik stuck with this story and over several more phone calls, Kelly began to realize that her son had somehow come upon a large amount of money. Pawlik started telling her he’d earned it by investing in Bitcoin. It sounded crazy, but then again, Pawlik had figured out how to invest in Bitcoin and even taught his stepfather how to do it years ago. Still, none of it added up.

How, in the late afternoon on March 11, Pawlik ended up on 40th Street in the side yard between two houses is anyone’s guess. But he was carrying the cash and a computer in his backpack as well as the pistol. Whatever he was trying to do — run from someone, hide, stash the money in a secret location, or just rest for a few moments — he wouldn’t finish.

[pullquote-6]Someone called the paramedics because he was unconscious. Swift, his friend and former case worker, remains perplexed by the entire series of events.

“He wasn’t someone you would find passed out on the sidewalk,” she said. Pawlik was an addict, but he didn’t use heroin in unfamiliar, exposed public places. “It doesn’t sound like the type of neighborhood he’d be hanging out in, and a location where he’d fall asleep,” she said. “It seems like there would have been some events leading up to that where he would have been attacked or harmed by someone else.”

A couple weeks after Pawlik was killed, his friends held two separate vigils. One was on the Oakland street where he died. The other, in San Francisco — the city that had become Pawlik’s home — started at the Civic Center near the fountain. But before they could finish setting up candles and pictures of their friend, one of the anti-homeless street sweeping crews arrived along with a couple cops. The police ordered Pawlik’s friends to leave. They scrambled to pick up the makeshift altar and moved to Minna Street, where another “sweep” was underway, so they moved again to Stevenson Street, another back-alley haunt, but again police told them to disappear.

Howe said the vigil’s repeated displacement was ironic. It mirrored the lives of so many homeless youth, unable to find a place, a physical and psychological sanctuary, in which to take shelter, even if just temporarily. Pawlik’s community couldn’t remember his life without being pushed along by authorities.