Back in 2007, Michal Migurski noticed that the City of Oakland’s crime-mapping site, Crimewatch, was nearly impossible to navigate — not to mention stuck in the late Nineties, design-wise. The site contained useful information, but because of its clunky interface, it wasn’t really helpful. But for Migurski, who works at an online design and mapping firm in San Francisco, it provided the perfect challenge.

For weeks, Migurski worked late at night hacking the city’s data, trying to find a way to take the daily crime stats and create code that would present the information in a new, user-friendly format. With the help of his colleagues, he created Oakland Crimespotting, a website that allows people to track crimes by date, neighborhood, and crime type, all laid out on a relatively intuitive interactive map. The website became an instant success: Neighborhood crime prevention councils, which previously had to hunt down data from the Oakland Police Department, now had better information with just a few clicks. Oakland Crimespotting was, essentially, a timesaver for everyone involved. And, as the saying goes, information is power.

As a Code for America fellow in 2011, Max Ogden created apps for the City of Boston. Now he’s one of many hackers trying to help Oakland. Credits: Wes Sumner

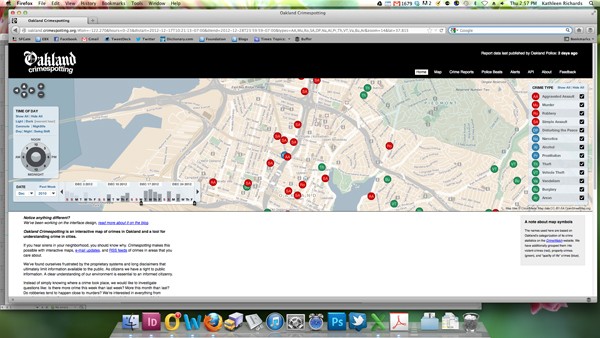

Oakland Crimespotting allows people to easily see crime happening in their neighborhood.

Nicole Neditch is trying to bring Oakland out of the Dark Ages of the Internet. Credits: Wes Sumner

Code for America founder Jen Pahlka believes transparency can change the relationship between people and government.

Matt Senate is one of the founders of Sudo Room, a new hackerspace in downtown Oakland that caters to all kinds of hacks. Credits: Wes Sumner

Nine months after the site went online, however, the city blocked Migurski from retrieving any more of its data. “They weren’t too happy about it,” Migurski recalled. “They felt that we were misusing the service and putting undue stress on their servers. I don’t think that was the case because at this point we’d been running the site for months. It wasn’t anything new.” However, a few months later, the city had a change of heart. Instead of just letting Migurski continue as before, officials promised they’d start providing him with the information on a daily basis. And in the five years since, the city has never failed to deliver. The city’s initial misgivings weren’t entirely surprising, Migurski noted. “We were basically asking something of them that they’d never considered giving out before,” he said. But the city’s shift in attitude reflects a sea change in government that’s taking place across the country — not just in Oakland.

In 2009, so-called civic hackers like Migurski were given the equivalent of a divine ordinance. That’s when President Barack Obama issued the Open Government Directive, a memorandum that called for increased transparency in government by freeing up data for everyone to use. Since then, more and more municipalities have been working with civic-minded hackers to help cities make websites and apps that matter. The idea is that data — whether on crime, budgets, liquor licenses, or disease outbreaks — can be organized and presented in a way that’s more useful to the public. And giving people greater access to data not only increases transparency, but it also makes people better informed. The ultimate goal is to create a more engaged citizenry, which, in the grandest Obama vocabulary of the movement, is “the essence of democracy.”

“It’s a new definition of transparency,” said Jen Pahlka, an Oakland resident and founder of Code for America, an organization that brings together cities and hackers to solve problems using technology through a year-long fellowship program. “Transparency shouldn’t just be about holding your government accountable; it’s about changing the relationship between people and government.”

And there’s perhaps no better place for such a movement to take root than in Oakland, where a combination of factors — a tech-savvy workforce; an activist-oriented, DIY-minded populace; and a cash-strapped government with few resources — make for a ripe environment in which to create meaningful breakthroughs in civic hacking. Thanks in large part to the city’s new online engagement director, Nicole Neditch, the city has been actively working with hackers on various projects: In December, more than one hundred librarians, students, small business owners, city staff, and coders attended City Camp, an event at City Hall that aimed to get different groups of people involved in finding creative technological solutions to city problems. On January 3, three Code for America fellows will begin an eleven-month project to build much-needed apps for the city. And later this month, the city will roll out an “open data portal,” freeing up more than thirty datasets on crime, property, and public works requests, which they hope will be put to good use by the city’s intrepid coders.

Certainly, these endeavors are admirable. But the goals they aim to achieve — and whether they can actually achieve them — aren’t so clear-cut. Getting people to actually use the apps, sustaining the sites after the hackers have left, and dealing with the city’s still-significant digital divide are only some of the challenges these new measures face, and for that reason it’s unclear whether they’ll actually lead to a more efficient, let alone a more democratic, Oakland.

Advocates of civic hacking note that the technology is simply a means to an end, not the end in itself. Oakland Crimespotting, for example, was successful because it allowed people to easily see the crime in their neighborhoods, and gave them a platform for a more productive conversation about crime. “It’s not about the technology,” Pahlka said. “It’s about the people and the conversation they are having.”

Perhaps, but in a city fraught with complex problems, are apps really the answer to Oakland’s woes?

For many, the term “hacking” still mostly brings to mind negative connotations. “It probably got misinterpreted as a negative term for breaking security systems in the Seventies or Eighties,” Migurski said. But for a long time, the term simply meant “finding interesting, weird, or elegant solutions to a problem.”

The story of hacking begins with model trains. In 1946, a group of MIT students started the Tech Model Railroad Club to fiddle with and build an elaborate system of miniature trains. Half of the club was in it for pure nostalgia: They painted the meticulous replicas and waxed poetic about an aging pinnacle of high-speed transportation. The other contingent, dubbed the “Signals and Power Subcommittee,” oversaw the massive wiring that powered the elaborate system of crisscrossing train tracks.

Using stray equipment cobbled together from the campus phone system, the S&P members strung together wires and dials that allowed for complex manipulation of the miniature trains. In 1959, they wrote a dictionary for their particular jargon, which became the foundation of hacker culture. Hack: 1) an article or project without a constructive end; 2) work undertaken on bad self-advice; 3) an entropy booster; 4) to produce, or attempt to produce, a hack. By taking existing stuff, tinkering with it, and figuring out how to give it a clever new purpose, these students were producing what they called hacks.

And this spirit remains largely the same in today’s generation of self-identified, decidedly non-nefarious hackers. Such was evident on a Friday evening in December, when a group of them gathered on the second floor of an office building on 22nd Street and Broadway for the opening party for Oakland’s newest hackerspace, Sudo Room. The event included at least some of the typical party indicators: people, bottles of whiskey and cheap wine, and the glaring buzz of dubstep floating above the awkward party chatter. But there were also scattered laptops, a giant vat of an experimental kombucha brew, more than two hundred books on topics as disparate as coding language and law, and equipment for radio broadcasting. Sudo Room intends, like the Model Train Club before it, to cater to all sorts of hacks.

Most people, however, were huddled around a contraption attached to a door leading to the office from the elevator. Someone across the room typed something onto his laptop and shot a thumbs up; a second later, a round piece of bright orange plastic over the door’s lock made a whirring sound, a dial turned, and the lock popped open. The hackers were enthralled. It wasn’t just a party trick — it was the group’s first hack. Rather than distribute keys to all the members of the hackerspace, the hackers wrote some simple code, used their 3-D printer to make precisely modeled plastic discs, and strung them together with roughly $5 worth of hardware to engineer a way to open their building’s door just by entering a password online.

“But the best thing is, we’ve created a solution that other people now don’t have to work to create,” said Matt Senate, one of the founders of the space who is also a member of Open Oakland, a motley crew of around twenty civic hackers whose goal is to change Oakland with technology. (Full disclosure, I’ve known Senate since college.) The code and the 3-D models are all available for free online, so anyone with basic coding know-how can set up a similar system.

That’s one of the central tenets of hacking culture: copy everything and share everything accordingly. (Sudo Room’s door displays a giant yin-yang with “CTRL-C” and “CTRL-V” written above and below it — the keyboard commands for “copy and paste,” a mantra equivalent to “live free or die.”) The idea is that only by operating in a completely open environment where collaboration can occur can ideas be constantly improved. The same premise defines the so-called “open source” movement, which focuses on code that is freely available for everyone to take, remix, and refine to their specific needs.

It’s an idea rooted in efficiency: Why reinvent the wheel when you could spend that same time making a much more awesome wheel?

Cash-strapped public agencies could especially benefit from this concept, but not surprisingly, they’ve been slow on the uptake. “Cities, as much as you try to get them to copy each other, they’re way too adamant about not doing that,” said Max Ogden, a former Code for America fellow who spent most of 2011 creating apps for the City of Boston and who now spends much of his time hacking in Oakland. “They act like ‘copy’ is a bad word, but it’s what open source is based on.”

Accordingly, one of Code for America’s main goals has been to get cities to become more comfortable with the idea of copying each other. The same code used to make Code for America’s “Adopt a Hydrant” site in Boston, for example — which encouraged residents to take responsibility for individual fire hydrants, which often get buried in snow — was used to make an “Adopt a Siren” site in Honolulu, where there is currently a problem with people stealing batteries from tsunami sirens. Earlier this year, the City of Chicago bought a bunch of beer, recruited some civic hackers, and launched “Adopt a Sidewalk” with a similar premise: to get citizens to work together to shovel snow from pavement in their neighborhoods.

Meanwhile, some cities are investing in tech innovation as a permanent fixture of government. In 2010, Boston’s City Hall created an Office of New Urban Mechanics, and a few weeks ago Philadelphia followed suit. The departments basically serve as low-cost research and development: Bring together civic hackers, fiddle with existing code, and test out new ways of solving old problems. “I think more cities are realizing you don’t have to be really up to date with technology to innovate,” said Code for America’s Pahlka. “You can tackle these things without upgrading all your systems and being a state-of-the-art city.”

And yet, while other cities have chief innovation or technology officers, in Oakland — where city staff has been slashed by 25 percent over the last ten years due to budget cuts — an in-house R&D department is just a pipe dream. In the meantime, these projects largely rely on the efforts of online engagement director Nicole Neditch. “As cities all over the country have had to downsize, by opening up data and engaging citizens, it’s a way of being able to do more with less,” she said. “Ideally we’d like to have a bunch of people dedicated to doing those things, but right now we’re just trying to get people across departments to think about things in a new way in the first place.”

At Oakland’s City Camp event in December, city employees abounded. But Neditch stood out. A tall woman with girlish features who — when not busily typing on her laptop — is usually smiling and shaking someone’s hand, Neditch is at least a decade younger than most of her peers at City Hall. She’s also one of the city’s newest hires, tasked with bringing Oakland out of the Dark Ages of the Internet and into the 21st-century world of online interaction. Along with City Councilwoman Libby Schaaf and Communications Director Karen Boyd, Neditch was one of the main backers of Oakland’s partnership with Code for America. Schaaf calls Neditch a “goddess” for her efforts at championing technology in City Hall.

And she’s just the right person to do it. Neditch is a programmer, a former co-owner of the cherished Oakland institution Mama Buzz Cafe, and helped launch Art Murmur. She is, in many ways, the very embodiment of community-minded, DIY Oakland.

And she cares — a lot. On Tuesday nights, chances are you’ll find her cooped up in a small conference room in City Hall long after most city employees have gone home. That’s when members of Open Oakland meet to work on projects as diverse as visualizing budget data and making an app that allows citizens to adopt storm drains in their neighborhoods.

The group officially launched in August after co-captains Steve Spiker and Eddie Tejeda realized that hackathons — day-long coding events focused on quickly churning out apps — were too limited in scope. “We realized doing a hack event once a year for the city just didn’t cut it,” said Spiker. “It wasn’t sufficient that we just did this one thing and then let everything drop.” It was also partially the result of Code for America’s new endeavor to complement its fellowship program, encouraging civic hackers across the country to organize into regularly meeting coding groups called “brigades.” According to a Code for America representative, Open Oakland is now one of the biggest — and most active — brigades in the country.

Tejeda had just finished a Code for America fellowship in New Orleans — which in 2010 had the most blight of any city in America — helping to make a site that allowed people to search by address to find out the status of blighted properties. Previously, people had to wade, by phone, through a complex web of bureaucracy to find out the same information, but now they can see the status of a blighted property with just one click. “It’s not just stats — it’s specific places, specific people, specific impacts,” said Tejeda. “Now people can ask the real questions.” In other words, finding out the information shouldn’t be the hard part.

It’s this same mentality that’s informed much of the work that Open Oakland has strived to do. And, luckily, there’s no shortage of hackers dedicated to doing just that. “That’s one of the reasons we knew Open Oakland would work,” said Spiker. “We knew there were a whole bunch of people in Oakland with incredible skills that had good jobs in tech, but they weren’t the kind of jobs that were going to change the world in any way.” Or, as Neditch said, “It’s really just the tech version of Oakland’s diverse community of people who like to participate. It’s a general DIY way of thinking.”

It’s certainly impressive that a group of twenty people with day jobs devote outside time simply to help make their city’s clunky technology flow more smoothly. To outsiders, it may seem like a puzzling dedication to working on incremental projects with no concrete end goal in sight. But the question is: How long can it last?

When Oakland’s three Code for America fellows arrive in February, they’ll be embedded in city government for a full month. Working with Neditch and others, it’ll be their jobs to identify the city’s shortcomings and try to create technological tools that will have the greatest impacts. When Oakland and eight other cities were chosen out of the 29 that applied to have fellows for 2013, Neditch and Boyd suggested some starting points: fixing the city’s cumbersome contracting processes (currently largely done on paper) and coming up with a better process for public records requests. It remains to be seen whether these are the projects the fellows will ultimately pursue, but, as Tejeda said, “Building the tools is actually the easy part. The difficult part is actually understanding what you need to build.”

And in an effort to spur more civic hacking efforts beyond the Code for America work, Neditch is working on creating an open data portal for the City of Oakland — originally proposed by Councilwoman Schaaf in April — to house more than thirty datasets held by the city. “For now it’s going to be sort of the low-hanging fruit of what’s already available online in some form,” said Neditch. The portal, however, will be a single repository for all the information, constantly updated and able to be synced or downloaded for easy access.

Similarly, the city recently debuted Engage Oakland, a site meant to serve as a community board for citizens to pose questions to city officials, or comment on other people’s ideas to improve the city. In the future, Neditch envisions city staff taking an active role in responding to and participating in the forums on the site. In the most utopian sense, Engage Oakland would blur the divide between City Hall and citizens so that all community members can be heard — not just those who show up to city council meetings.

While all these measures have just been rolled out in the last year, what’s clear is that within City Hall, this movement is being viewed as a sea change in how government operates. “I think it’s a culture shift among city employees that no longer see [open government] as threatening, and are actually excited and hungry for it,” said Schaaf.

What’s less clear to see in the haze of fancy interactive websites and apps, however, is the actual impact they will have. The language of Code for America, the city, and the hackers is often unimaginably grand in scale, with all roads inevitably ending at “a truer democracy.” Multiple people I spoke to invoked the desire to revert back to the early days of collaborative government, with the Internet eventually shepherding in a bygone era of town hall-like participation. The goals are commendable, to be sure, but even the most useful website isn’t really that useful at all if no one uses it.

“It’s something I struggle with every day,” said Neditch. “There is this jump to technology as the solution to increasing engagement, but it’s definitely not the only step we have to take.”

Spiker echoed a similar sentiment. “A lot of the things we’ve seen being done with open data so far are technology vanity projects,” he said. “But there have been a number of things that really have been transformative, I think.

“Right now if you want to start a business in San Francisco, you can find vacant properties, search by neighborhood, find characteristics of nearby businesses, and check out crime and foreclosures in the area,” he continued. “You’d get a very comprehensive picture of all the things you’d need to know to locate and invest in the city. In Oakland, however, none of those things exist, except for being able to look at Crimespotting.”

And as far as getting people to plug in, Code for America is beginning to emphasize that aspect more as well. In the next year, it’ll be pushing cities to do what’s essentially basic marketing around the sites. After all, people are more likely to use sites if they know they exist.

But in Oakland, the challenges remain great. The digital divide continues to be a persistent problem. Open Oakland, for example, is mostly made up of young white males, representative of the mostly young white tech sector that it’s largely drawing from.

But the problem, said Dennis Rojas, director of East Bay Job Developers and a board member for the Latino Connection PAC, is only partially the skills gap; it’s also about how the conversation is being framed. “I think people hear things framed in terms of being about tech and think, this is something that doesn’t concern you. But this is something that very much concerns you. It’s not about hackers and computers and technology; it’s about your community, your issues, and keeping your neighborhoods clean and safe.”

While the City Camp event, which Rojas attended, was incredibly successful at bringing together disparate communities, he emphasized that those types of events can’t just be happening downtown. “I’d like to see something like this happen in East Oakland. One of the challenges with communities of color is that they’re very cynical of government, and it’s because they’re not part of the conversation.” Holding an event like City Camp downtown — far away from many of the communities excluded from the conversation, he said — just pushes them farther away.

And it’s not lost on many hackers that, despite the city’s many efforts toward open government, Oakland has had some issues with transparency. City Administrator Deanna Santana, who has been very supportive of Oakland’s open government initiative, has also come under fire for her efforts to redact portions of a report that strongly criticized OPD in light of its heavy-handed response to Occupy Oakland (see “Deanna Santana Tried to Alter Damning Report,” 9/19/12).

The issue highlighted one of the specific challenges that Oakland faces moving ahead with open government initiatives: trust. Almost every civic hacker I spoke to mentioned mistrust of government as a major hurdle in Oakland, but also one that their efforts are precisely designed to combat.

“I think one of the biggest problems we’ve faced is that whenever government operates in a closed fashion, it just asks for and results in distrust and concern that government isn’t doing what it’s meant to be doing and isn’t willing to be questioned,” said Open Oakland’s Steve Spiker. “But there is a love for this city that’s very strong and very rich, and it’s got a history of social activism that’s carried over in a lot of ways to the tech community.”

In the meantime, the biggest question may be whether these projects can stay afloat. After all, Michal Migurski created Oakland Crimespotting for free, and while he’s not planning on shutting it down anytime soon, that doesn’t change the fact that its existence relies entirely on him. He’s made the site’s code available for free online, but if city employees don’t pick up the slack, it would take another civic hacker to keep it going.

“[The] short answer is that I don’t think it’s particularly sustainable,” said Migurski. “I’ve been looking at the history of public transportation, which looks a lot like the current data movement. Initially, it was all housing developers laying it out: They’d rip up streets, put down tracks, and it was a really cowboy-ish kind of setup.

“My sense about the civic coding thing is that you still need people who have the itch, interest, and energy to bring the data out in the open and show there’s a demand there, and then over time it will be a thing that is expected of cities to provide for their citizens,” he continued. “This isn’t a cool faddish new thing; it’s a thing like police, fire, and transit that citizens need. It’s a responsibility that governments have, especially with something like crime. You already run the police, you already collect that data, so it makes sense that the people who collect that data should also be responsible for sharing it with the public.” According to a representative from Code for America, its fellows will spend the last few months of their program in Oakland transitioning the maintenance of their sites and apps to the city. Whether city staff will actually be able to sustain the projects is another matter.

Given these issues, perhaps it’s wise to have tempered expectations. At City Camp in December, there was no final product, no shiny semi-tangible app or repository that contained the fruits of eight hours of theoretical problem-solving. But when the final closing remarks were given and the last person left the stage, most people were lingering. Attendees were clustered together, talking about things they’d discussed during the breakout sessions of the day, or about their personal projects. Many people exchanged email addresses to meet up at future dates. The event was more than just the sum of its parts; it was simply the beginning of a conversation.

The conversation about Oakland may be long, and it may be complicated, but it’s no more long and complicated than the discussions happening in Detroit or New Orleans or Philadelphia. The conversations are happening, but for now, the important ones are still happening offline.