When Mayor Jean Quan introduced her plan last month to build 7,500 units of new housing in Oakland, she pointed out that the city has plenty of vacant land available for development. “We’re not San Francisco,” she said. “When we build something we don’t have to push people out.”

While Quan’s so-called 10K-2 plan is patterned after former Mayor Jerry Brown’s 10K initiative, which brought 10,000 new residents to Oakland’s Uptown, downtown, and Jack London districts, her proposal aims to differentiate itself by building housing “throughout the city, in every neighborhood,” she said. “And I make a commitment to try to make sure that at least 25 percent of those new homes are also affordable.”

Although affordable housing advocates applaud Quan’s commitment to building affordable units in Oakland, there are questions as to whether the mayor will be able to keep her promise, because the city currently does not have the funds to make it happen. In addition, there are concerns about whether Oakland has sufficient laws to prevent low-income tenants from being forced from their homes by rising rents once the 7,500 new units of housing are built.

In the past, some cities in California financed affordable housing through so-called “inclusionary zoning” rules, which required rental housing developers to make some of their units affordable. But then in 2009 a California appeals court ruled that inclusionary zoning was illegal. The ability of cities to build affordable housing then suffered another major blow in 2011 when Governor Brown and the state legislature killed redevelopment — a property tax mechanism that raised funds for affordable housing and other economic development projects.

Building affordable housing now “is such a great need, and the price tag is so high, we need to turn to both public and private sources of funds,” said Richard Marcantonio of the public-interest law firm Public Advocates, which pushes for more affordable housing in the Bay Area.

However, powerful developers’ organizations are working to whittle away cities’ ability to get affordable-housing funds from developers. In a case currently before the state Supreme Court, the California Building Industry Association (CBIA) is challenging a San Jose requirement that condo developers create some affordable units.

The CBIA is a heavy hitter — it was among the biggest contributors to Brown’s 2012 gubernatorial re-election campaign. And last year, the governor vetoed a bill that would have overruled the 2009 court decision and restored the ability of cities to establish inclusionary zoning requirements, also known as inclusionary housing. Brown believes that inclusionary housing requirements stifle market-rate development by making construction too costly. “As mayor of Oakland, I saw how difficult it can be to attract development to low- and middle-income communities,” he wrote in his veto message. “Requiring developers to include below-market units in their projects can exacerbate these challenges.”

Yet even with the limitations on inclusionary housing laws, Marcantonio said there are still a lot of options for including affordable housing in market-rate development projects — options that Oakland has yet to take advantage of. Some Bay Area cities, for example, make deals with developers, offering to waive height-limit rules, to fast-track their permits, and to provide other incentives in exchange for promises to build or pay for affordable housing.

Another option, said Jeff Levin, policy director for East Bay Housing Organization, is charging “impact fees.” He explained that “the development of market-rate housing increases the demand for affordable housing [because] it increases the demand for services and retail.” So some cities charge market-rate developers a fee to help build housing for the workers the new residents will require.

Oakland has not yet adopted any of these policies, but members of the city council’s Economic Development Committee expressed eagerness during their March 25 meeting to explore the idea of charging developers impact fees for market-rate housing. Councilmember Lynette Gibson McElhaney reported that Milpitas requires developers to pay a $32,000-per-unit impact fee — and the committee asked staff to report on the possibility of adopting such a policy in Oakland.

Meanwhile, Oakland’s Housing and Community Development Director Michelle Byrd said Oakland is moving ahead with 1,100 units of affordable housing in the pipeline. She pointed out that the plan for Brooklyn Basin, a 3,100-unit housing development southeast of Jack London Square, calls for 465 of the units — 15 percent — to be affordable.

“We’re continuously looking at funding opportunities to continue the great work we’ve done to date,” Byrd added. She said the city also plans to apply for state support. Oakland officials are also joining advocacy efforts for a bill now in the legislature that would raise money for affordable housing with a fee on non-residential real estate sales. Byrd’s department also is developing a “Housing Equity Roadmap” plan for the city, which it expects to release in late June.

But even if the city meets its goal of 25 percent affordable units in new developments, that won’t necessarily prevent the housing projects from pushing more low-income people out of Oakland, said Robbie Clark, a lifelong city resident and housing organizer for Causa Justa/Just Cause. New housing developments likely will bring higher-income people into Oakland’s neighborhoods, he said. “That brings in businesses that cater to higher-income people. You see the neighborhood change. Landlords see the opportunity to get higher rents.” Landlords raise rents when someone moves out — or look for ways to get lower-paying tenants to leave, he added.

Levin of East Bay Housing Organization agreed that there is a need for increased protection for tenants faced with “the risk of displacement in areas coming under heavy development pressure.” As an example, he praised the move by the city council two weeks ago to limit landlords’ ability to raise rents to pay for capital improvements.

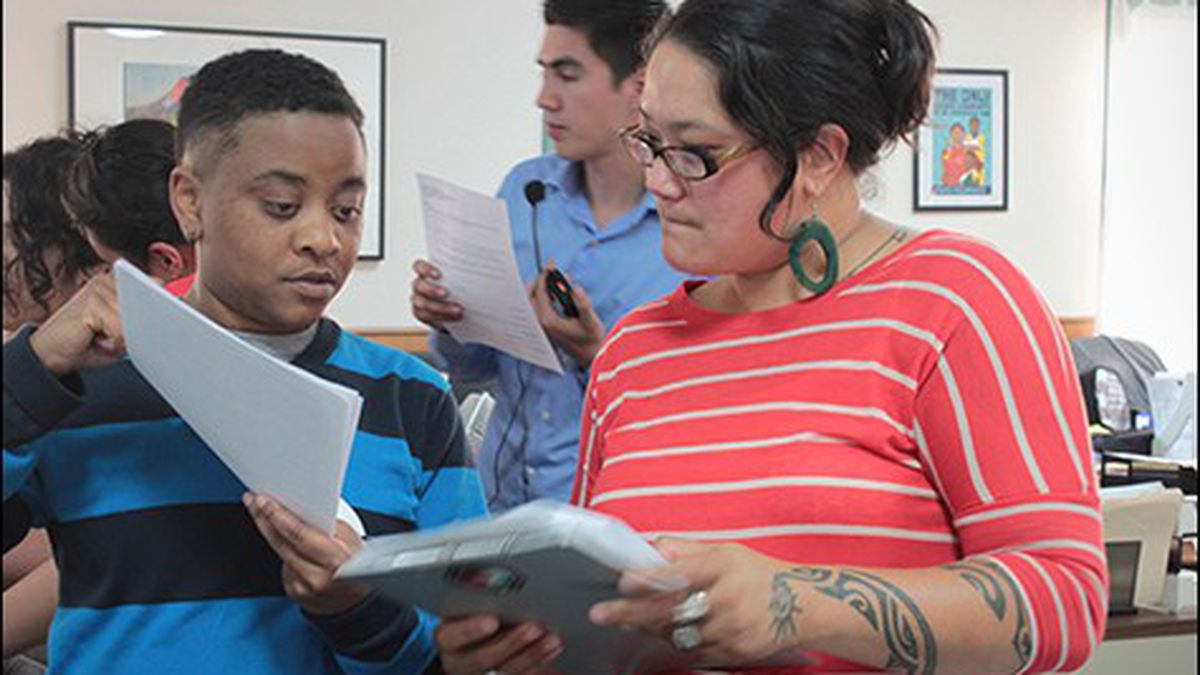

Fresh from that victory, representatives of Causa Justa/Just Cause are now planning a November ballot measure that would target another strategy they say some landlords use to evade Oakland’s protection from unfair evictions. The measure would impose fines on landlords who harass their tenants by failing to make necessary repairs, threatening or physically intimidating them, interfering with their privacy, discriminating against them (especially immigrants), and other tactics.

Both Causa Justa/Just Cause and the Oakland chapter of Association of Californians for Community Empowerment, a social justice nonprofit, also see better enforcement of the housing codes as a much-needed tenant protection. They want the city to put more resources into code enforcement, especially in rental housing, and specifically to hire more code-enforcement staff. “In Oakland, it’s clear that a number of residential properties haven’t been adequately maintained,” said Clark. “It’s important to prioritize existing housing as much or even more than new housing.”

Another key protection against displacement, he added, is to ensure that landlords pay moving and relocation costs for tenants who must move out for major repairs — and to guarantee those tenants the right to return to their homes when the repairs are finished. Causa Justa/Just Cause have teamed up with the Alameda County Department of Public Health to write “Development without Displacement,” a report with more detailed information and recommendations, to be released April 7.

Some measures to protect tenants are now illegal, however, because “landlords have tried to weaken rent control at the state level,” said Dean Preston, executive director of the statewide organization Tenants Together. In 1995, the state legislature approved the Costa-Hawkins Act, which bars cities from extending rent control to vacant apartments, single-family houses, and condominiums, along with newly constructed buildings. Many cities, Preston explained, made a deal with building owners to get rent control accepted, limiting it to housing built before the law was passed — in Oakland’s case, the city’s rent control law only applies to multi-unit buildings constructed before 1983. Costa-Hawkins also locks in dates such as those, making it illegal for cities to revise them.

The Ellis Act, passed by the legislature in 1986, allows landlords to evict all their tenants if they are going out of the rental-housing business. This law has become a center of controversy in San Francisco, where, Preston said, “speculators have created and exploited a loophole [in the law] to convert buildings to condos or tenancy-in-common.”

This isn’t a big issue in Oakland, Preston said, but it could be soon, as prices rise. Despite the Ellis Act, he said, cities can fight these evictions by making them less profitable. For example, San Francisco imposes “significant relocation payments” — up to $15,000 per unit — for tenants being evicted under the Ellis Act. And cities can regulate what owners do with the buildings afterward, for example, by putting restrictions on condo conversions.

Advocates are also asking the question: Affordable for whom? Quan’s State of the City report states that “the city will prioritize housing for a range of low-income and middle-class units.” But Levin said his organization is “pushing a definition of affordable that would be for families at or below 60 percent of the regional median income. That would be up to about $45,000 a year for a family of four.” He said they also want “as much [housing] as possible for very low income [households], but that requires more subsidies.

“We’re very happy to see that affordable housing is part of [the 10K-2] initiative,” Levin added. “It’s important that we get it right this time, with the income mix. To use a variety of tools so we’re not just producing upper-income housing but housing for working families. We want to make sure people who have been here in hard times benefit when development comes to Oakland, to preserve the diversity that makes Oakland a vibrant place, to keep it the Oakland everybody loves.”