Even as a 6.5-ton Japanese robot named “Kuratas” was bearing down on Matt Oehrlein and Gui Cavalcanti and preparing to bash them with its 600-pound metal fist, their strange dream had come true. They were fighting in the world’s very first giant robot battle.

It was October 2017. After challenging Suidobashi Heavy Industries’ robot to a one-on-one fight to be streamed around the world via Twitch.tv, the two cofounders of MegaBots Inc. were about to find out if the robots they’d spent years building in West Oakland could better their opponent in a three-round fight to the death. The loser would be the team whose pilot surrendered, or whose robot was knocked down or incapacitated.

Matt Oehrlein and Gui Cavalcanti in front of Iron Glory and Eagle Prime. Credits: Photo by Greg Munson

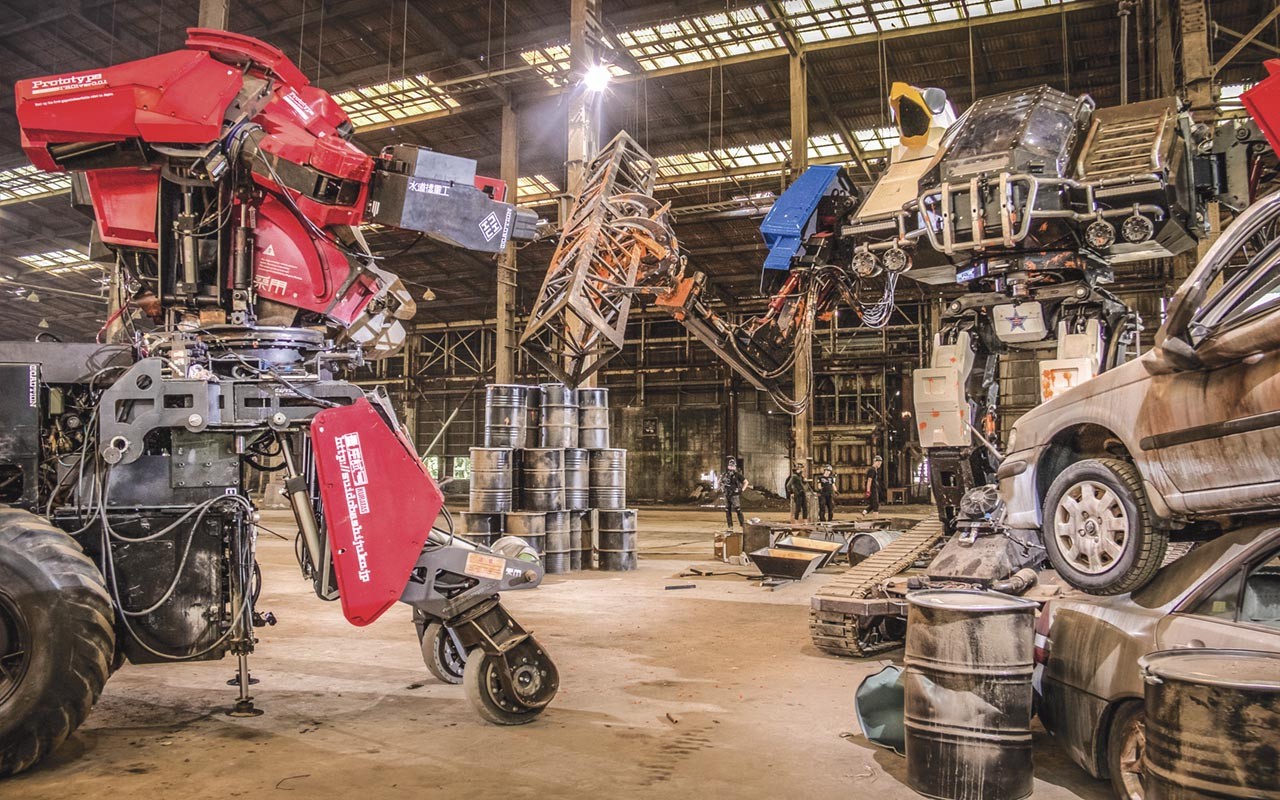

Eagle Prime, at right, spins a lighting stanchion in its 2017 battle with Kuratas, left. Credits: Photo by Micheal Maudlin

Matt Oehrlein and Gui Cavalcanti inside the cockpit of Eagle Prime. Credits: Photo by Greg Munson

Having disassembled and transported their Mark II “Iron Glory” and Mark III “Eagle Prime” robots to Japan and then reassembled them at a steel mill converted into a makeshift combat arena, Oehrlein and Cavalcanti were realizing their dream. But it looked more like a nightmare.

As the first round opened, Iron Glory fired a three-pound cannonball at Kuratas, only to have it shatter in the chamber of its cannon. The Japanese robot promptly charged across the warehouse and struck Oehrlein and Cavalcanti’s robot with its titanic fist. Iron Glory immediately toppled onto its back, putting the pilots’ helmets, roll cage, five-point harnesses, and fire-retardant clothing to the test. Fire extinguishers at the ready, the MegaBots support crew ran over to pull the pair out of the cockpit. Someone asked urgently, “Anyone smell gasoline?” As Oehrlein slowly emerged from the cockpit, he minced no words: “That sucked.”

The fight was over almost before it had begun. After only 24 seconds, MegaBots had lost round one to Suidobashi in humiliating fashion. One more loss and the match would be over.

In round two, Oehrlein and Cavalcanti abandoned Iron Glory for their newer Eagle Prime robot, complete with modular weaponry; a double-barrel cannon arm; a flexible steel claw for grappling; and other advancements. More importantly, Eagle Prime weighed in at 12 tons, with 60 percent of that weight centered toward its bottom, as opposed to the top-heavy weight distribution of the 6-ton Iron Glory. Oehrlein and Cavalcanti hoped that Eagle Prime’s extra weight would give it an advantage over the 6.5-ton Kuratas.

As round two began, Eagle Prime fired a cannonball, which again shattered in the chamber as it had in Iron Glory. Kuratas took cover behind a stack of oil drums arrayed as props. Eagle Prime fired again, this time destroying some of its opponent’s cover. Closing in for another round, Eagle Prime hit Kuratas dead on. The Japanese ‘bot then launched an aerial drone to distract Eagle Prime’s pilots, who swatted it out of the air with their robot’s giant claw. But the damaged drone crashed atop Eagle Prime’s cockpit, its smoke obscuring Oehrlein and Cavalcanti’s view.

Kuratas charged again. Eagle Prime blocked its advance by knocking a stack of demolished prop cars into its path. But Kuratas simply raced around the blockade, engaging Eagle Prime up close, and bashing it several times with its mighty 600-pound fist. Eagle Prime wrapped its claw around Kuratas’ arm to neutralize the giant fist. The Americans fired several paintball rounds into their opponent’s exposed midsection before repurposing their cannon as a battering ram, knocking several of Kuratas’ armor panels loose. With the Japanese robot seemingly immobilized by Eagle Prime, the second round was called in favor of MegaBots. The score was tied, with one final round to go.

Dismayed at the poor performance of their cannons, Oehrlein and Cavalcanti replaced Eagle Prime’s arm with a 4-foot, 40 horsepower chainsaw originally designed to cut through rock. When the third round began, the American robot charged out of the gate, closing the distance with its Japanese foe. In an effort to neutralize Eagle Prime’s cameras, Kuratas began firing paintball rounds using a six-barrel Gatling gun built into its right arm. To block the barrage, Eagle Prime pulled down a nearby lighting stanchion with its claw, spinning it on its axis to block the Japanese robot’s fusillade of blood-colored paintballs. Oehrlein and Cavalcanti advanced. As the giant robots collided and grappled, the Japanese robot dislodged some of Eagle Prime’s front bumpers.

Then the Americans activated Eagle Prime’s chainsaw. The blade cut through the Japanese robot’s arm like it was a loaf of bread. Red paintballs spilled onto the floor and the Gatling gun’s barrels fell to the ground like severed fingers. Eagle Prime redeployed its saw and started dismantling Kuratas’ shoulder. As the much larger Megabot pushed the Japanese robot backward, it knocked down another lighting structure in a giant shower of sparks and dust, sending a camera crew and a pair of announcers scurrying for safety. Just after a closed-circuit video feed showed the Japanese pilot mopping his brow in anguish, the round and match were called in Eagle Prime’s favor.

After 18 months of negotiations, planning, building, and deployment — but only 204 seconds of actual combat — MegaBots had handily bested Suidobashi before an audience of more than 286,000 streaming viewers on Twitch.tv. It was the online gaming network’s second largest non-gaming stream to date. The match can be found in its entirely on YouTube via a quick search for “MegaBots vs. Kuratas.”

Viewers of the match had conclusively proven that there is an audience for a giant robot-fighting league.

Yet that left a larger, more challenging question. Is there also a viable business model?

If a giant robot-fighting league ever does come to pass, BattleBots probably set the whole thing in motion.

Debuting in 2000, the television series BattleBots challenged teams to build their own robots and pit them in three-minute matches against robots built by other teams. The metallic combatants were divided into weight classes — Lightweight (60 pounds), Middleweight (120 pounds), Heavyweight (220 pounds), and Superheavyweight (340 pounds) — with the goal being to damage, disable, immobilize, or destroy the other team’s remotely controlled robot to earn as many points as possible and proceed to the next round. The show lasted five seasons on Comedy Central, with later incarnations appearing in 2015 and 2016 on ABC, and a new edition currently airing on the Discovery Channel. Fanatical viewers sided with their favorite robots and the teams that created those ‘bots from an almost endless variety of designs, the appeal being the visceral joy of watching their favorites crush, impale, stomp, burn, and obliterate their opponents as they moved toward victory.

To Matt Oehrlein and Gui Cavalcanti, the next logical step was to create a giant fighting robot. In their vision, that robot would be piloted by a person or persons who actually rode inside it.

Oehrlein and Cavalcanti met up in the Boston area, engineers who’d each run “maker spaces” — rented facilities in which people gather to work on various technical construction projects. Oehrlein was on the verge of an interview with famed robotics company Boston Dynamics when the two began discussing their shared interest in maker projects and robotics. Along with Andrew Stroup, the pair eventually founded MegaBots Inc. in Somerville, Massachusetts, prior to moving the company out to the Bay Area. They headquartered in Hayward, and began building robots in West Oakland’s American Steel complex.

MegaBots first exploded on the Bay Area pop culture and entertainment scene in 2015, by bringing their new Iron Glory robot to the annual Maker Faire in San Mateo. With its ability to crush cars; fire three-pound, 3D printed, paint-filled cannonballs at 130 miles per hour through car windows; and inspire the imaginations of crowds who loved the idea of giant robots, it became an immediate crowd pleaser.

“We do things like appliances, washing machines, dishwashers,” Oehrlein said. “And when they watch the robot do it, it’s really, really impressive.”

But Oehrlein and Cavalcanti had a bigger goal than merely smashing appliances at Maker Faire.

“The goal has always been from the very beginning to do stadium-sized robot battles,” Oehrlein recalled. “So, yeah, in five years, I see something like 60,000 people in a stadium cheering for their favorite robot team.”

Thanks in part to the reaction of crowds at Maker Faire, the men discovered that they could turn such demonstrations into a fundraising technique. Members of the public would pay to destroy things, with each dollar bringing MegaBots that much closer to financing its robot sports league.

“When people hear the words ‘giant fighting robots,’ they mostly think of a Transformers movie,” Oehrlein said. “They expect Optimus Prime to jump into the sky and grab a helicopter and throw it into the ground and all kinds of really crazy stuff. The reality is that MegaBots is never going to live up to what can happen in Hollywood movies. We have to obey the laws of physics and the limitations of today’s technology. But, the advantage we have is our robots are real. People can actually touch them and get inside them and it’s something that can happen in people’s lifetimes.”

Today, you can visit MegaBots.com to book your own $1,149 session piloting Eagle Prime. “Crush it!” the website exhorts. “Unlimited power at your fingertips. Buckle-into the gunner’s seat and wield Eagle Prime’s massive claw that exerts over 3,000-lbs of crushing force. Eagle Prime is hungry for some smashing time and needs you behind the joysticks to make it happen. We’ll feed you TVs, old couches, appliances, or any ‘specialty items’ you might want to destroy with a giant robot! Bring your friends because they’re not gonna believe this.”

And if just controlling the robot’s arm is not sufficiently fulfilling, MegaBots also offers a “‘Full-blown Pilot Experience.’ Instead of just controlling Eagle Prime’s arm, you’ll control the whole damn thing. Pilot all 15-tons of powerful fighting machinery — chainsaw and all — and be the envy of all your friends. Now is your chance to experience what has been nearly everyone’s dream at some point. Options include: Co-piloting with a friend, vehicle destruction, and flamethrower attachment.”

A video on the website shows an overjoyed young woman named Whitney crushing and then flipping over a large printer or copier in a scene inspired by the cathartic copier destruction scene in the movie Office Space. Oehrlein said the strangest item destroyed to date was a piano. “Cars are always a favorite because you know they’re really big and everybody kind of has a feel for it and you watch the robot pick it up as easily as you’d pick up a rock.”

Peter Lenarcic, a 56-year-old Fairfield automation supervisor with extensive mechanical experience, booked time in May and October of 2018. His roughly $1,000 booking fee bought him a full hour in Eagle Prime, with about 15 minutes of orientation and 30 to 45 minutes of run time. Lenarcic received cockpit orientation, inserted himself into the roll cage, and strapped into a 5-point racing harness to keep him safely in his seat. Asked to describe the experience of smashing things in Eagle Prime, his reply was like listening to a child joyously extolling the features of his or her favorite new ride at an amusement park.

“The power as you embody a Powerful Giant Mech is exhilarating,” Lenarcic wrote of his experience. “You simply BECOME a 15-foot-tall, two-ton giant that can smash things with huge fists!” MegaBots provided Lenarcic with a La-Z-Boy recliner and an old big-screen projection TV to smash for his first booking. During his return trip, he smashed dishwashers and a car.

“Arm-smashing is by far the best,” said Lenarcic, who said he enjoyed the bounce, the power, and the ground-shaking feedback from this. “The chainsaw is more of a continuous destruction,” he noted, recalling the fun he had tearing the roof off a car by forcing the running chainsaw through its windshield.

When asked whether he’d book time again in the future, he replied, “Of course!”

Oakland software product manager Justin Quimby had a similar experience. “It was everything I hoped for, and an absolute blast,” recalled Quimby, who had grown up watching TV shows and reading science fiction about giant battle robots. Once the safety protocols and training were complete, Quimby’s dream of robotic destruction came true. In his case, the victims included a washing machine, a few pieces of furniture, and a car, all provided by MegaBots.

“Matt and the team gave me a briefing beforehand, talking me through the various controls and how the robot operates,” the 44-year-old recalled via email. “Once we got into the robot, we went through a pre-flight checklist and then they walked me through how to operate each part of the robot. Once I was comfortable with each part, they let me loose to wreck a car!”

Quimby was impressed by the safety measures in place beyond the roll cages, emergency shutdowns, and fire extinguishers that he expected. “The other key safety measure was the MegaBots crew,” he added. “Not only was a team member in the robot and able to take over should something get squirrely, they were also communicating with two team members on the ground, who made sure that nothing happened which might have caused an issue.”

“I was grinning ear to ear the entire time, when I wasn’t yelling out in joy.”

As Oehrlein and Cavalcanti dreamt of giant robot combat while raising money and perfecting their machines, they weren’t alone. Upon noticing that the Japanese firm Suidobashi Heavy Industries had built its own giant robot, the two went to work crafting a challenge video from the Oakland warehouse space they were renting at the time.

They donned matching black sunglasses, wore American flags as capes, and walked past bursts of flame as patriotic music surged in the background. Their message was simple: “Suidobashi, WE have a giant robot. You have a giant robot. You know what needs to happen …”

The challenge video went viral.

The next stage involved about 1½ years of negotiations between MegaBots and Suidobashi Heavy Industries, with initial negotiations taking about a year, and the next six months devoted to various amendments. While certain points were more formal — such as number of rounds in the match — Oehrlein noted that this was brand new territory for both parties. “Because this was the first-ever giant robot fight in history that we are aware of, the rules were basically negotiated by us asking each other ‘we’re going to build this, is that OK?'” he said. The major point of contention was that Suidobashi wanted to fight Iron Glory first, and not Eagle Prime.

To help pay for the contest, MegaBots lined up a streaming deal with Twitch.tv, the Internet-based gaming platform, where viewers watch elite video game players do the things they’re best at. Through the Twitch platform, top gamers can make more than a million dollars per year via subscriptions, sponsorships, and a share of ad revenue. Oehrlein said MegaBots coordinated the Twitch deal on its own and owns all rights to the duel itself.

When the contest was streamed, more than 286,000 viewers tuned in via Twitch. And since the contest, videos of the fight have been viewed on YouTube more than 8 million times. Indeed, social media marketing is a big part of the MegaBots business model. As of this writing, the company boasts more than 153,000 YouTube followers, 217,000 Facebook followers, 25,000 Instagram followers, and 9,000 Twitter followers.

Looking back at the Kuratas fight with the benefit of hindsight, Oehrlein sees both strengths and weaknesses of the match, with an eye toward how future contests could be improved.

“I think the strength was the novelty of it, first and foremost,” he said. “The fact that no one had ever seen two giant robots battle each other in real life, pretty much ever. It was a historic moment to witness that for the first time. That fact that we have a nation-on-nation narrative also makes it very interesting.

“We truly didn’t know what was going to happen when these things started hitting each other. When two giant robots that were made on two different sides of the world met together for the first time and started hitting each other, no one knew if they would fall over, would they not move at all, would they get pushed around? Would they just hit each other and lock up and shut down? It was incredible.”

However, Eagle Prime’s huge size advantage turned out to be an unforeseen yet key variable in the fight. “When we met in that warehouse in Japan, that was the first time we ever saw their robot,” Oehrlein said. “We just had a way bigger, more powerful robot. I don’t think there’s anything that they could have done short of disrupting our electronics somehow.”

But that wasn’t all that the contestants discovered. It was only after the first battle that the true costs of their endeavor could be fully understood. The entire three-round match, which was gripping yet oddly anti-climactic, had taken just three minutes and twenty-four seconds. Yet it cost MegaBots roughly $5,000 just to replace the bumpers that were damaged when Kuratas charged Eagle Prime in the third round. Based on the devastation that Eagle Prime’s chainsaw exacted upon Kuratas, Suidobashi’s repair costs were probably much higher. And all of that was nothing compared to the cost of disassembling, transporting, and reassembling the giant robots across the ocean, along with the costs of travel and accommodations for the 12-member MegaBots crew, the two pilots included. Oehrlein said those costs approached $100,000.

Since the battle, which was recently awarded a Guinness World Record in the category of “Largest Robots to Fight,” other potential competitors from several countries have expressed interest in building a fighting robot or creating a challenge of their own. Perhaps most prominently, MegaBots has been called out by the makers of a Canadian robot named Robo Dragon, a giant, diesel-powered, car-eating, fire-breathing dragon.

“There are a number of teams around the world that are interested in fighting. The tricky part is financing it,” said Oehrlein, who cited no less than three different teams in China he’d be excited to fight if given the opportunity. “We’re considering things like ‘Do we just build all the robots ourselves or do we have a bunch of teams build them?’ The advantage of building all the robots yourselves is you can get economies of scale and control how the events look and feel a little bit better. But then you lose a little bit of uniqueness in the robots. What people especially like about BattleBots is they get to see all their favorite teams come up with these creative designs and it’s kind of like a ‘may the best design win’ type of thing.”

By itself, a robot fighter can be constructed for about $500,000, Oehrlein said. But the total costs of this line of work are significantly higher. Even with $3.85 million in seed capital from corporations such as Autodesk and assorted venture capital firms, MegaBots now finds itself needing additional capital to make its long-term goal a reality.

“We can definitely build incredible robots, we can make some great YouTube videos and we can get some attention, but now we need the expertise on the team and the capital to turn this into a global touring phenomenon,” said Oehrlein, who estimates that a sum in the $50 million range might be necessary to make a robot-fighting league self-sustaining. “It takes a lot of investment to get to that point. But it requires an investor with an incredible vision to invest meaningful amounts in something that is only starting to generate interest and traction.”

Now that Oehrlein is more cognizant of these challenges, his company has entered a period of restructuring. Cavalcanti parted ways with MegaBots in 2018 to build aquatic robots at Otherlab and his own new startup, Breeze Automation. Oehrlein, meanwhile, has made some money investing in apartment buildings, conceding that it’s a steadier vocation than MegaBots, while only taking up a fraction of his time. The time away from MegaBots has allowed him to put some things in perspective. “I haven’t made any plans for a vacation yet,” he said, “but they can be useful for disconnecting from the day-to-day and assessing things from a 10,000 foot view.”

Looking ahead, MegaBots plans to branch out and create additional income streams before it builds more robots, Oehrlein said. Sponsorships, event appearances, lines of both toys and apparel, a MegaBots video game, and reality shows involving the pilots and pit crews are all on the drawing board. The company has been able to raise more than $700,000 in appearance fees, alongside paid rides, YouTube ad revenue, sponsorships, paid appearances on TV shows, merchandise sales, and video licensing. In the meantime, Bay Area residents can help the cause by backing MegaBots on the fundraising website Patreon, Patreon.com/MegaBots.

MegaBots still needs to figure out whether its vision is economically sustainable. It may or may not be the company that ultimately makes a giant robot-fighting league come to life. But it wouldn’t be for lack of trying. MegaBots laid the groundwork and paved the way. And whether its finds the resources it needs or others pick up where the original duo left off, giant fighting robots have arrived. And if MegaBots gets its way, Oehrlein and Cavalcanti’s dream could come true: a world where one of the entertainment options on a Saturday night includes your favorite giant robot fighting its opponents to the roar of tens of thousands.