His intent had been to design an earthquake-proof home for his parents after Loma Prieta in 1989, and he had heard about how this tiny animal was the only creature known to have survived outer space.

“And that’s impossible,” Tssui said. “What could possibly survive for ten days in outer space, with nothing?”

So, naturally, he built a house that was modeled after the tardigrade’s anatomy.

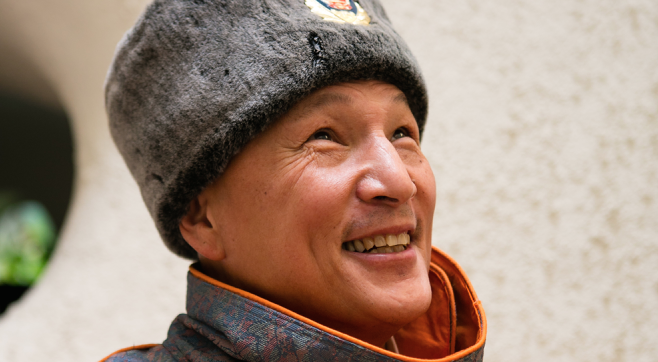

With apologies to Dos Equis, the most interesting man in the East Bay isn’t some Hemingway clone in a beer commercial, but rather this mild-mannered Chinese-American architect.

The first thing everyone notices is Tssui’s clothing, which he designs himself, and looks like something taken off the set of Star Trek. Many of the outfits are fitted with solar panels and zippers positioned at precise angles to minimize arm strain. (Tssui’s wife, Elisabeth Montgomery, a school superintendent in China, said he’s sometimes mistaken for a matador.)

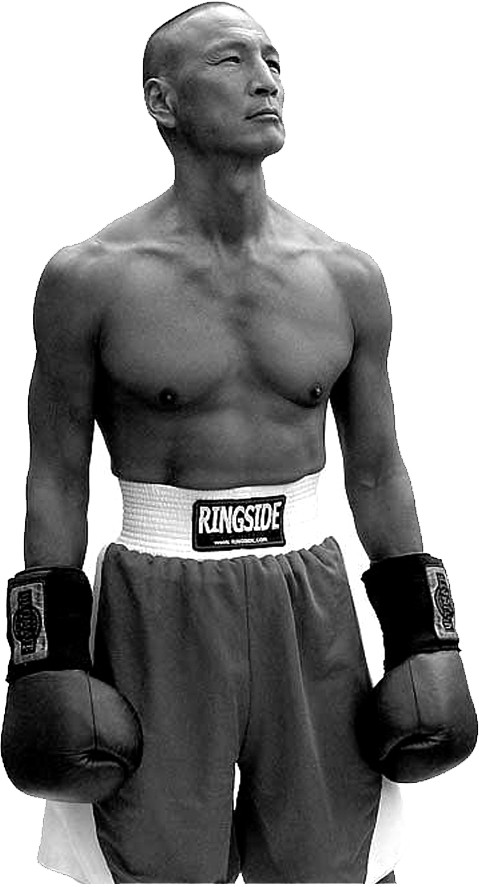

His business card lists his occupation as architect, author, and “polymath nonpareil.” He fancies himself a kind of jack-of-all-trades who composes music, plays the piano and flamenco guitar, and designs furniture. He’s also an eight-time amateur boxing champion, and four-time Senior Olympics gymnastics champ. Even now, at 62, he wrestles at an intramural club at UC Berkeley, hitting the mat with college kids one-third his age.

So far, he thinks it has worked out pretty well.

But what distinguishes Tssui from your typical Berkeley eccentric is his ideas about architecture. You could fill several books with his fantastical, curvilinear creations — each hyper-eco-conscious and inspired by something in nature, each as peculiar and futuristic-looking as the Fish House. You’d be hard pressed to find a single straight line in his entire oeuvre. In his own words, the buildings are “like something you’d find on Mars or another planet.”

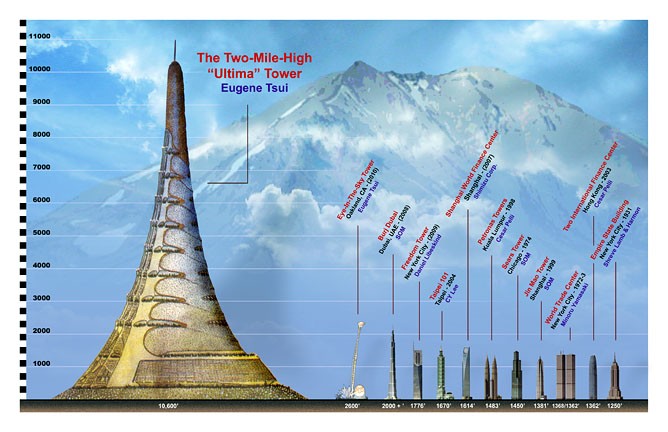

His most famous design is the Ultima Tower (pronounced “ul-TEE-ma”): a two-mile-tall building that would be tapered toward the top, like a termite mound. Its proposed footprint would occupy one square mile of San Francisco’s Financial District — and, because of its tremendous height, would allow room for about one million people to live and work inside.

At one point, he pitched officials in Tangier, Morocco, and Tarifa, Spain, on his design for a floating bridge that would span the Strait of Gibraltar, allowing people to easily cross back and forth between Africa and Europe by car, foot, or even horseback. Once built, the bridge would surely be considered the Eighth Wonder of the World, Tssui insisted.

He designed an entire city that would float along in the middle of the ocean, out beyond the territorial waters of any sovereign nation so that the people living there wouldn’t be bound to follow any particular country’s laws. And here in the East Bay, he once proposed the construction of an “Eye-in-the-Sky Lookout Tower”: a 2,340-foot-tall, twisting, helix-shaped observation tower in downtown Oakland that, at nearly four times the height of Seattle’s Space Needle, would have been the tallest building in the world at the time.

But all of these high-concept projects have one thing in common: None of them have actually been built.

Indeed, for much of Tssui’s life, it has been steady conflict with mainstream architectural trends — and with a world that isn’t quite ready for someone like him — that has defined him, almost as much as his ideas themselves. But now, he believes his designs might play a role in helping to solve the day’s most pressing problems: an unprecedented housing crisis and an environment in even greater peril due to Trump’s presidency.

If the Ultima Tower were built, for instance, “it would set a precedent for what cities of the future could be.” It would prove that cities can thrive without having to decimate the environment.

Back at the Fish House, Tssui spoke at length about the tardigrade’s ability to adapt to even the most extreme environments. He might as well have been talking about his own career, one riddled with frustration and doubters. Why wouldn’t he relate to the tiny tardigrade — its dogged persistence, how it keeps plugging away in the face of whatever challenges the world throws its way?

“You have to be a radical,” he said. “You have to do things that you believe in.”

Rebel With A Cause

Tssui’s story starts out not so differently from many classic immigrant tales: Born in Cleveland, Ohio, he was the son of an academic and a Beijing-opera-singer-turned-physical-therapist. They came to the United States for graduate school, and were forced to stay when the Communist Party came to power in China in 1949. Tssui spent his formative years in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and, as he tells it, he was a bit of a rebel right from the start. For instance, he was the only boy in his school who signed up for the sewing class even though the other kids would laugh and call him a sissy. When it came time to choose a profession, Tssui was certain that he wanted to become an architect, even though his parents urged him to live a quiet life as a doctor or lawyer. It was the Seventies, however, and Tssui says his ideas about design — which, even then, rejected the prevailing aesthetic of right angles and straight lines — were too extreme for the mainstream.

Tssui’s refusal to compromise wound up getting him kicked out of two architecture programs, at the University of Oregon and Columbia University. After that last expulsion, in 1976, he apprenticed for several years under Bruce Goff, whose whimsical designs had earned him a reputation as the “wild man” of American architecture, at Goff’s firm in Tyler, Texas. Eventually, Tssui completed his degree at UC Berkeley. But, for the most part, his ideas are all his own.

In Evolutionary Architecture, the book in which the architect maps out his design philosophy, Tssui writes that, even as a teenager, he wondered why all the buildings he saw around him were marked by sameness — “lifeless, cubicle, and mediocre variations of some impotent, yet omnipresent mind.” He opens the book with this question and hypothesis: “If nature has built, tested, and perfected architectural structures for more than 5 billion years, then what would our human-made structures and environments look like if we directly applied this knowledge from nature?”

Other architects have drawn inspiration from the natural world, of course, but very few on the scale that Tssui has attempted. For instance, the Ultima Tower was conceived as a response to the way he believed San Francisco had been blighted by the “continuous disseminating reach” of urban development. The solution, he concluded, was simple: Build up.

That’s not a novel idea to anyone familiar with the ongoing debate over “density” in urban development. But, of course, Tssui took this to an unprecedented extreme: As conceived, the Ultima Tower would be approximately four times as tall as Dubai’s Burj Khalifa, the current tallest building in the world.

It isn’t difficult to see why there has been scant interest. When Tssui first drew up his plans for the Ultima Tower in 1991, he estimated that the project would cost $150 billion and would take 25 years to complete. What public official would want to make that pitch to the people?

What’s more, Tssui’s intent was for this one skyscraper to replace San Francisco altogether. Eventually, the city as it exists would be razed to the ground or allowed to fall into decay. The stated goal of the project, after all, was to drastically reduce the city’s footprint, returning the surrounding area to its pristine, natural state.

It’s important to note, however, that Tssui never viewed the Ultima Tower as some kind of theoretical exercise. He believed, and still believes, that the project is 100 percent viable based on technology that already exists — that the only thing missing is political willpower.

And it’s hard not to admire the level of detail that went into the design: There was the maypole-like suspension system, which would hold the entire building up from above, so that the whole thing would sway in the breeze and be flexible like a human spine, or the Golden Gate Bridge standing upright. That flexibility is what would make the building earthquake-resistant, Tssui reasoned — unlike the rigid, heavy steel constructions that make up the bulk of our city landscapes.

And because the building would be no bigger than one mile in width at any point, people wouldn’t need cars anymore, either. Instead, they’d travel from floor to floor via high-speed elevators powered, at least in part, by windmills that would supply much of the building’s electricity.

Sound a bit too much like science fiction? That’s probably why the project is now mostly relegated to truth-is-stranger-than-fiction news blurbs and top-ten lists of “Fascinating Buildings Never Built,” instead of on any urban planner’s actual agenda.

Indeed, Tsui has faced rejection throughout his career. His ambitious, high-concept visions generate a certain amount of buzz because of how unusual they are — but rarely get anywhere close to getting actually constructed.

Meanwhile, Tssui’s more modest projects are met with a similar degree of skepticism, if not outright hostility.

Take the Fish House, for instance. An East Bay Express cover story from December 1, 1995, entitled “Not in My Backyard,” documents the prolonged saga that ensued when neighbors in that quiet West Berkeley neighborhood first got wind of Tssui’s design. “It’s not that I don’t like the house,” one neighbor told the Express back then. “Somewhere else it might be okay, in the hills, for example, or with more space in the desert. In Disneyland I think it’s a cool house.”

Tssui recalls that the criticism usually followed the same set of themes: “I don’t want to look at this gigantic eyeball,” or “Why should we have a science-fiction spaceship in our backyard?”

He said that most of those original neighbors have moved away in the subsequent years. Now, if anything, he thinks most people who move into the area think of the house as a charming neighborhood quirk. (Mark Paddon, a member of the small startup company that now uses the Fish House as a live-work space, says neighborhood kids are always asking if they can see the inside.)

More recently, Tssui has encountered similar challenges in his attempt to build a new live-work space for himself on an empty plot of land in a residential neighborhood in San Pablo. Renderings of the proposed building, which he dubbed “Telos: Window to the World,” show ruffled edges around the exterior that are reminiscent of a coral reef, and a cocoon-like viewing platform that would open up, via hand-crank, like a lotus flower. Stationary bicycles would supply much of the electricity for the house, and Tssui anticipated using the site as a kind of educational center.

City records obtained by the Express show that San Pablo’s planning department had a generally favorable view of the project as recently as March 2013, citing the ways in which the house would help the city achieve its sustainability and energy efficiency goals. But administrations change, and in Tssui’s view the new planning director simply hated the aesthetics of the Telos design. He says she told him that it didn’t fit with the appearance of the neighborhood’s existing buildings, and basically squashed the project.

Elizabeth Dunn, who was assigned to be the lead planner on the project in March 2016, said that’s not exactly what happened. She acknowledged that mismatching aesthetics might have eventually been a concern for a neighborhood of modest homes built in the Fifties and Sixties, but said the project was stopped in its tracks for other reasons — including Tssui’s intent to use the home as a public gathering place, which hadn’t been approved, and their failure to submit an updated geotechnical review for the project after they turned in a new application to build it as a bed-and-breakfast. With those concerns left unaddressed, the city withdrew the application last May.

When asked if she thought any form of the project has a chance to be approved in the future, Dunn demurred, but said that in 25 years of work as a city planner she hasn’t ever encountered anything quite like this.

“The design is very different,” she said.

‘Like Tupac’

Naysayers notwithstanding, Tssui has picked up no shortage of admirers over the years. He said that, since the early Nineties, he has taken on at least 500 interns, many of whom he says have gone on to achieve great success.One of those true believers is Derick Lee, founder of San Leandro-based tech incubator PilotCity, who interned with Tssui in 2010. Lee explained that he was first attracted to Tssui for the same reasons as everyone else: “He was wearing capes. He had a Wikipedia page. He was weird. He was a world champion boxer and gymnast and also an architect. He was designing and wearing solar-panel suits. He was making YouTube videos.”

Lee said he believes the reason Tssui hasn’t achieved the level of architectural success he deserves is that he isn’t business-minded — doesn’t really focus on negotiating deals or making money.

“He’s going to be one of those people like Tupac,” Lee said. “He’s going to be way more famous when he dies.”

Fred Stitt, director of the San Francisco Institute of Architecture, described Tssui as a “visionary” architect, and said his lack of built projects is just the price he has to pay for being ahead of his time. By way of example, Stitt said that Frank Lloyd Wright was in his seventies before he received any recognition for his work.

“Eugene will have imitators who will dial down his design enough to be more acceptable to the mainstream. Then he’ll get some credit. No telling how long that might take,” Stitt said.

If Tssui is to find the mainstream success and recognition he seems to crave, it might have to be in another country — maybe China, where in Tssui’s experience people are more attracted to, and have more experience with, the kinds of big, flashy projects that he has proposed.

Indeed, for Tssui’s latest — in Guizhou, China — it appears he has been given free rein to design an entire city. Specifically, the project is a collaboration between the LiBo County Municipal Government in the Guizhou province and the Hong Kong Tourism Research Institute, which hired him to design a kind of “tourist village” dedicated to preserving the traditional culture of the Yao minority ethnic group. Tssui explained that the Yao society isn’t based on modern technology — it eschews things like automobiles and cellphones. These days, though, more and more of the younger generation are leaving their villages and integrating into modern Chinese society, which means the entire culture is in danger of being lost.

Tssui has been tasked with designing a new kind of city, where a particular tribe of roughly 35,000 people can live, but that will also include a museum about the indigenous Yao culture, a new school system based around that culture, and buildings modeled after iconography that’s significant to the Yao people — a giant spider web, a “waterfall gate,” and so forth. Ecologically-friendly features will include an innovative rooftop water-catch system and chimneys shaped like water buffalo horns that will serve as a natural air-conditioning system.

The idea is that tourists will come from all over China to stay among the Yao people, maybe for a weekend or longer, and that they’ll be able to learn from their culture — which, in Tssui’s view, is superior to our modern, technology-dependent culture. At the same time, the tourism would provide a source of income for the Yao, and would mean that the next generation wouldn’t have to move to the big cities in search of jobs.

It all sounded a bit strange — a little too much like putting an Indian reservation inside of Epcot Center — but Tssui said he and his Chinese partners have been working in close collaboration with the Yao people.

“I’m hoping that this will be a new world model for development that respects the culture that’s being shown,” he said. “That way, ancient wisdom can be passed on for the general public.”

In an email, Chen Yun-Gang, who heads the Chinese team working on the project, said that when he first met Tssui, it was as though Superman had descended from Mars — someone from an alien planet come to save the people. Chen believes Tssui is one of just a small number of architects who really care about helping the Yao people — who wouldn’t just treat the project as a business opportunity.

And unlike so many of Tssui’s American projects, this one might really be on track to happen: Chen says construction on the first part of the project is slated to begin in May 2018. The estimated total budget, to be provided by some combination of Chinese government funding and investment from socially-conscious entrepreneurs, is roughly $14 million — a significant sum, but a lot less than, say, $150 billion.

In the meantime, Tssui has to content himself with designing smaller, slightly less ambitious projects, and seeing them come to fruition. He’s well-enough known at this point that kindred spirits tend to find out about his work and gravitate toward him. Tssui cited as one example a motivational speaker in Florida who has contacted him about trying to raise enough money to build that floating city.

There’s also Eileen McDilda and her husband, Wayne, who were trying to figure out what kind of house they wanted to have built on farmland outside of Austin, Texas. She saw a documentary about Tssui on TV late one night. She had an idea that she wanted a round house, or even more intriguingly, a house shaped like a Mobius strip — inspired, she said, by the land surrounding the dam on her property, which slopes downward on one side and upward on the other. She hasn’t officially hired Tssui yet, but it seemed to her that he might be the perfect person for the job.

“I think he’s a fine human being,” McDilda told the Express. And while she hasn’t asked Tssui to do any drawings yet, “I’m sure that it’s simmering along somewhere in the back of his brilliant brain.”

‘Aggressive Courage’

What, then, would it mean for Tssui’s legacy if none of his most ambitious projects ever get built?During one of our first email exchanges, Tssui sent me a Word document of an essay about him, which one of his admirers had tried to submit to The New York Times. The title alone — “Eugene Tsui: Hero and Visionary of Our Times” — left little question as to the tenor of the piece, which casts Tssui as a Randian hero-architect in the mold of Fountainhead protagonist Howard Roark, so famous/notorious for the way he valued individualism above all else, in the face of a society hell-bent on forcing him to conform.

It’s clear this is more or less how Tssui views himself, too — that despite his philosophical musings and his mild demeanor, he’s driven by a competitive fire.

Conversations would often span several hours, and when my questions were exhausted, Tssui would jump in as the interviewer — “What are your dreams, Luke? … What’s your Ultima Tower?” Sometimes, he’d even interview himself: “If you had asked me, ‘Eugene, what is the trait that is most in you that’s unlike other people?’ And I would say, ‘aggressive courage.’”

Charles King of Oakland’s legendary King’s Gym, who trained Tssui for eight consecutive amateur boxing championships, said his fighting style “had a way of making people looking bad.”

“All of a sudden they got hit, and they wondered where it came from.”

Along those lines, of the architecture professors who criticized his work early in his career, Tssui said his prevailing thought at the time was, “Someday I’m going to crush you.”

And, in many ways, he believes he has already won — his ideas about ecology, biomimicry, and “green” architecture have already become much more widely accepted than they were when he started out in the Seventies.

Is it really important, then, that Tssui witnesses the completion of the Ultima Tower before he’s dead?

In a word, hell yes.

“I want to prove to people that it isn’t just a pretty idea — that these are very meaningful and helpful structures to help evolve the state of humanity,” he said. And he wants to be around to defend those buildings — to educate the public on their importance — even after they’ve been built.

At the age of 62, he has entered what most would consider the autumn of their careers. But Tssui said that he plans to, in all seriousness, live to be 150 years old.

“Architecture is one of the slowest professions. You have to live a long time to see it happen.”