Francisco Perez has lived in his apartment near International Boulevard in the Fruitvale district of Oakland for 20 years. “It was good for a long time,” he said. Then four years ago, the rent started going up steeply every year.

Perez explained that’s when the owner learned the building was not covered by rent control because it was built one year after Oakland’s rent control law was passed. By now, Perez said, his rent has more than doubled. He retired six years ago and feared he wouldn’t be able to keep up.

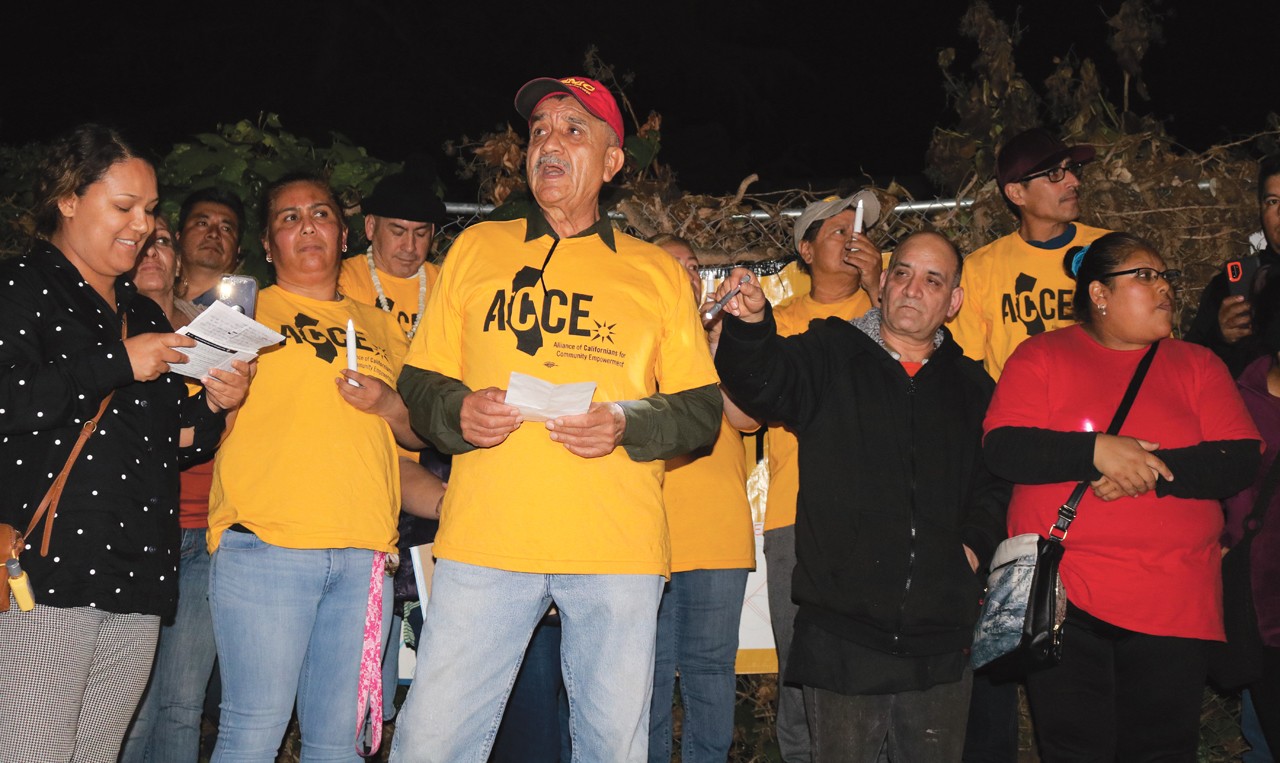

“ACCE showed us how to fight for tenant rights and how to raise our voice,” Maria Montes de Oca said. Credits: Photo courtesy of ACCE

Emilio Hernandez, Lillian Phaeton, and Christine Hernandez of 1432 12th Ave. Credits: Photo by Lance Yamamoto

Alexes Link has lived on 10th Street in Berkeley since she was three years old. Credits: Photo by Lance Yamamoto

But on February 27, he and other residents and their supporters gathered in the driveway of their 14-unit building for a victory celebration. After a five-month rent strike by half the residents, the building’s owner, Calvin Wong, had agreed the previous evening to start negotiating the sale of their building to the Oakland Community Land Trust.

Several tenants, including Perez, spoke in Spanish with English interpretation. They described the anxiety they had felt about the rising rents and their relief that a solution was in sight. “I feel so happy to know that we are in purchase negotiations and our lives can change,” said fellow tenant Jesus Alvares. “I believe that in the end my family, my neighbors, and I will be free from this stress and frustration.”

Many of the tenants said support from the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment (ACCE), a grassroots tenants’ rights organization, had been key to their success. “ACCE showed us how to fight for tenant rights and how to raise our voice,” said Maria Montes de Oca. “Thanks to our fight, we have been heard by the owner of this building.”

Residents said that at first they hope to pay rent to the land trust, whose mission is to keep rents affordable and prevent displacement. But over time they want to become owners of the building themselves. The Oakland Community Land Trust shares the goal of “creating opportunity for tenants to become owners,” said Executive Director Steve King. “We want to create structural transformation for low-income people to fundamentally change their relationship to the land.”

If the negotiations are successful, this building will join a growing number in the East Bay whose tenants have partnered with community land trusts, nonprofits that buy their buildings to keep them permanently affordable. And city governments are stepping up to support this strategy. Last summer Oakland allocated $12 million to support land trust projects in multi-unit buildings with five to 25 units. Berkeley also has a policy of supporting such projects and has created several funding streams that could help. “With public investment in Oakland, Berkeley, and San Francisco, community land trusts have been able to grow in the last two years,” said Miranda Strominger of the Bay Area Community Land Trust.

Now both Oakland and Berkeley are also considering ordinances that would incentivize or require sellers of multi-unit buildings to offer them first to tenants and/or the land trusts that are buying buildings to keep tenants from displacement.

Success Story

The home of twenty-six-year-old Alexes Link is one of the recent success stories: an eight-unit building on 10th Street in Berkeley, which the Northern California Land Trust is in the process of buying. Link has lived in the building since she was three, when she moved there with her grandmother, who raised her. Most of the building’s other residents are also African Americans who have lived in the building for decades. “We watch out for each other,” Link said.

Fellow resident Stanley Glenn agreed: “We’re a family.” Glenn, who recently retired from a job at Safeway in Berkeley, has lived in the building 27 years. “If you need something, there’s always someone who doesn’t mind doing it,” he said. And rent control has kept the apartments affordable.

One day last fall, Link said, a neighbor came and said, “Do you guys know your building is up for sale?” Link said that after she found the listing online, “most of the tenants were on edge. I was trying to find another place to stay, but it’s not easy. We were willing to fight to stay here.”

“We all got together and discussed it with the owner,” Glenn said. “We said, ‘we don’t want to be priced out, we don’t want to be displaced.'” When potential buyers came “we told them. ‘we’re not going to let this place go.'” Then in December the residents held a meeting with the Northern California Land Trust. “We all brought chairs and met in the driveway,” Link said. “We were ecstatic. We felt like we finally had someone on our team.”

Land trust Executive Director Ian Winters said the building was in danger of gentrification. “This was one outrageous displacement too many,” Winters said. Sales blurbs pitched it as a good building to “reposition,” a code word for corporate investors. The asking price “could only be supported if the current residents weren’t there.”

The land trust eventually negotiated a lower price and secured a “seller carry-back loan,” essentially a second mortgage from the seller. “We were able to negotiate fairly assertively with the seller,” Winters said. “We pointed out serious deferred maintenance issues.” And tenants’ opposition to a commercial sale was key.

The sale worked out well for both sides, said real estate agent Max Ratner, who represented the seller, Steve Bautista. The land trust was “a great buyer for the property,” he said, with the ability to take on the deferred maintenance problems. The seller was “willing to be flexible in a way some sellers would not be,” agreeing to wait for the land trust to assemble the necessary financing. And, Ratner said, Bautista “came to realize” that the carry-back loan benefitted him as well, providing regular monthly payments with interest over a period of years.

In addition, tenants helped convince the city to kick in $1 million for major rehabilitation. “I spoke at city council meetings,” Link said. “And we went to every meeting of the Measure O Commission,” which eventually allocated the funds.

A Growing Trend

As more people become aware of this strategy, more groups of tenants have been turning to land trusts to help them fight displacement. After the 2008 real estate crash, many of the Bay Area’s single-family homes were bought up by investors. Two years ago, members of the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment who lived in single-family homes owned by investor Steve Kalmbach got notice of a $1,300 rent increase. They began a campaign to persuade him to sell their homes to a land trust. After negotiations, petitions, and protests, including one at Kalmbach’s home on Halloween, the campaign succeeded. Oakland Community Land Trust bought the homes, and now the residents own them. ACCE communications director Anya Svanoe said another single-family-home “bulk purchase” is now in the works.

But most of the recent increase in tenant-initiated land-trust projects has come from groups of tenants in multi-unit buildings getting together and contacting one of the East Bay’s three land trusts. “We’re bombarded with folks wanting to bring their land into the land trust,” said King of the Oakland Community Land Trust. The Northern California Land Trust reported that the number of units they own has recently increased by about 50 percent.

“The goal is to make housing permanently affordable,” Winters said. “We have an anti-displacement focus.” King said land trusts do that by “removing land from further speculation.” Residents in Oakland Community Land Trust buildings are 90 percent people of color, he said, and all are low-income according to federal guidelines (currently that means an income under about $69,000 a year in the East Bay.)

In the classic model, the land trust owns the land and the resident owns the home with a restricted deed: When the owner sells, the price must remain affordable to low-income people. In practice there’s a wide range of arrangements in buildings owned by land trusts: some residents are renters, some own their individual units, some are organized as cooperatives. In all cases, though, the land trust tries to work out ways to share responsibility and decision-making with residents.

The two big challenges tenants face are persuading the owner to sell and finding a land trust that can put together the financing, which often includes substantial repair costs in addition to the purchase price.

Sometimes the owner is sympathetic and works with residents and the land trust. Because skyrocketing real estate prices have meant huge windfall profits for owners of Bay Area rental property, some sellers are willing to knock a little off the price when selling to a land trust, Winters said. “We also point out the tax advantages” of reducing the price, he added. “We say, ‘Would you rather give the money to the IRS and the Franchise Tax Board or to the people who made you rich?'” In rare cases the owner donates the building. The Bay Area Community Land Trust recently acquired a 10-unit building on Fairmount Avenue in Oakland from a woman who had inherited it, owned other property, and was concerned about possible displacement of the low-income residents.

A Rough Road

But in another building, which the Bay Area Community Land Trust is now in the process of buying, resident Christine Hernandez said “it’s been a rough road for us.” The seven-unit building on 12th Avenue in Oakland has followed an all-too-common pattern: a long period of disinvestment followed by foreclosure and threat of displacement.

“The guy who owned the building until recently was so neglectful,” said resident Lillian Phaeton. “All the systems in the building are bad,” agreed Hernandez. “When she turns something on in her unit, my electricity goes out.” Residents told stories of water leaks, gas leaks, exposed wires, clogged plumbing, mold, generations of pigeons living in the attic, and other hazardous conditions. During one incident, they said, it took the owner four days to respond to repeated calls reporting sewage backing up into the bathtubs. City inspectors said the house needed a new foundation.

The tenants described living under a state of siege during the last several years. The house was in and out of foreclosure at least twice. The owner, Robert Bennet, repeatedly told them to leave so he could make repairs, but went through no legal process and offered no relocation assistance, which the city requires owners to provide, tenants said. He also failed to pay utility bills, they said, for which he was responsible because the gas and electricity systems are not metered separately. Phaeton said she was able to keep the electricity on by switching the account to her name, but the residents — including three families with young children — went without heat or hot water for months.

Meanwhile Bennet borrowed money from a private lender, Michael Roy. “He said would invest in the property, but he never invested a penny” said Roy, who added that he is planning to “calculate my losses and take legal action.” Finally, Roy foreclosed and tried to sell the house at auction in spring 2019. The residents showed up with flyers informing potential buyers that the building “is occupied by tenants who know their rights and intend to defend them.” In addition, said Hernandez, “Everybody knew it was a dump.” The house didn’t sell, and Roy was stuck with the property, residents said. “We felt for him,” said Phaeton. Bennet did not respond to requests for comment.

Over the summer, Roy said, he put a lot of money into the house, including a massive cleanup of pigeon detritus in the attic, as well as a new paint job on the exterior and some repairs to a vacant apartment. Roy said he never intended to do the needed major rehab, just enough to enable the building to sell.

But residents feared that any if commercial buyer did the necessary repairs “it would jack the rent up so much we couldn’t afford to live here,” Hernandez said. A buyer, “who wanted to remain in the shadows” according to Roy, did sign a contract to purchase the building. But when his representative visited the house, residents said, they told him they would oppose the sale and “gave him a tour of all the things wrong with the building.”

Finally that buyer backed out and a sale to the Bay Area Community Land Trust is now in the works. “That’s better,” said Roy, “because the tenants wanted this and were going to be more cooperative. In Oakland tenants have a lot of power.”

The Bottom Line

Persuading an owner to sell to a land trust should get easier in Oakland and Berkeley if their city councils pass the “tenant opportunity to purchase acts” now before them. But the other major challenge is funding. To make this model work, Winters said, the land trust “has to get enough subsidy so paying off the mortgage plus ongoing maintenance can be done with affordable payments from residents.”

It’s the job of the land trust to stitch together that financing. “You don’t need money,” said Noni Session, director of the East Bay Permanent Real Estate Cooperative.” You just need credit worthiness,” which land trusts have. So some of the funding can come from a regular commercial lender. Some public funds are available for “green” improvement projects, and people who buy condos can get first-time homeowner assistance, Winter said.

A small percentage of the funding sometimes comes from residents and the community, he added. After Session’s organization recently partnered with a land trust to buy a building, they used crowdfunding to raise money for rehabilitation. Her organization is also working with federal programs and “mission-driven lenders” like credit unions and Community Bank of the Bay to create lower-interest loan funds for community projects. “You can get money from mission-driven lenders and leverage that to get more money,” she said.

A new philanthropic organization, the Partnership for the Bay’s Future, has a $500 million loan fund designed to “preserve, protect, and produce” affordable housing for the Bay Area. The partnership, initiated by the San Francisco Foundation, the Zuckerberg Foundation, and some private banks, also has recently given a round of grants to local governments, including Oakland, Berkeley, and Alameda County, to develop policies to promote affordable housing.

A growing network of support for land trusts and housing cooperatives operates in the background. The Sustainable Economies Law Center has long provided legal help and policy advocacy for collective economic activities and will soon launch a Radical Real Estate Law School to train lawyers to work with these projects. The California Community Land Trust Network shares resources and promotes favorable state policies.

At the grassroots level, the People of Color Sustainable Housing Network connects community activists working in many of these projects. It also partners with the Sustainable Economies Law Center to deliver a training program to equip low-income residents to launch their own projects. One such project is Richmond LAND, bringing together staff from several community organizations to plan new collectively owned low-income housing programs in that city. The Bay Area Community Land Trust gets funding from Berkeley to provide training for housing co-ops in everything from managing a capital fund to home maintenance to collective decision-making.

But eventually, Winters believes, “The amount of money needed, in large part, will have to come from the public sector. We need billions per county.” Traditional affordable-housing projects are large buildings with many units, supported by federal and state tax credits. But these programs are not geared to acquiring and preserving affordable housing in five-to-25-unit buildings, although King of the Oakland Community Land Trust said, “in our experience that’s where most displacement is happening.” That’s why Winters believes local support is key.

Berkeley passed its Small Sites Program to preserve affordability in such buildings in 2017, and recently gave a $1 million loan through this program to a project on Stuart St. There the Bay Area Community Land Trust is partnering with the McGee Ave. Baptist Church to rehabilitate a church-owned vacant building to provide low-cost housing to help stem the displacement of Black residents from Berkeley. Although Berkeley has recently created several funding streams to support affordable housing, Lewis of the Bay Area Community Land Trust said, “We still need a clear process by which we can access this funding.”

In Oakland, the city council allocated $12 million to support land trusts last July, after a campaign by tenant activists and land trusts. King, of the Oakland Community Land Trust, said this program is unique in the nation, enabling land trusts to leverage more money in the private market. With such local support, land trusts can grow to a significant size, said King. He pointed to the Champlain Land Trust in Burlington, VT, which now owns 10 percent of the housing there. “It’s a matter of political will,” he said.

Now the Oakland and Berkeley city councils are considering measures to make it easier for tenants and land trusts to acquire housing. These “tenant opportunity to purchase acts” would require sellers to give “first right of refusal” to tenants living in the building and/or nonprofits working with the tenants. Oakland city council member Nikki Fortunato Bas, who introduced the measure, said she was inspired by the Moms4Housing group, which took over a West Oakland house being kept vacant by an investor. After two months, the investor agreed to sell the house to the Oakland Community Land Trust.

Svanoe of ACCE said her organization was active in supporting Moms4Housing. It also has been talking with state Senator Nancy Skinner, who recently introduced a bill that tackles the large number of housing units being kept vacant by investors, like the one Moms4Housing occupied. The Skinner bill would allow cities to fine corporations for leaving homes vacant for more than three months — or to simply take over the property and rent it to low-income people, or sell it to a land trust. Her bill would also give tenants “first right of refusal” on foreclosed properties — addressing situations like the one faced by tenants in the 12th Avenue Oakland house.

Getting to Scale

Ultimately, land-trust advocates hope the state and federal government will provide support on a larger scale, pointing to a bill recently introduced in Congress by Rep. Ilhan Omar, which calls for a $1 trillion investment over ten years in “new public and private permanently affordable housing.” In introducing the bill, Omar commented “The private market will never be able to provide enough adequate housing.” And Bernie Sanders’ housing program explicitly calls for financial support for land trusts.

“As we continue to demonstrate the strength and stability of this model, I believe it can have a real impact on how we treat housing in our society,” said Strominger of the Bay Area Community Land Trust. “The foundation of this work is to demonstrate and actualize a different relationship to housing — that it’s not for profit. There’s a growing movement for housing as a human right.”

At a time of soaring housing prices and displacement, “This message needs to get out there,” said 10th Street Berkeley resident Glenn. “Up and down California, every city is going through it. The people are going to have to stand up.”‘