You enter the Transbay Terminal at 9 a.m. There is no baggage check, no metal detector, and no need to remove your shoes. The train departs on time, the seats are cushy, the leg room ample. It leaves San Francisco and heads south through the Central Valley, sweeping past gridlock at speeds up to 220 miles per hour. And before noon you’re in downtown Los Angeles, having never left the ground. At least that’s how it looks in the flashy YouTube video.

The proposed California high-speed rail system could be a reality within twenty years, despite being one of the world’s biggest infrastructure projects. But that depends on what happens in 2008, a year of reckoning for the $40 billion rail line. After more than a decade of planning that already has cost taxpayers $40 million, the proposal is still stuck in the conceptual phase. Most Californians haven’t even heard of it, due largely to state funding decisions that have kept the dream alive but not provided it the means to move forward.

However, the rail network could get its big break this year, with a $10 billion bond measure currently scheduled for November’s ballot. Project supporters say federal matching funds could be obtained, construction could begin by 2010, and a San Francisco-to-Los Angeles route could be completed within ten years. Momentum is building, and the project is gaining supporters.

“It’s the perfect storm right now,” said San Francisco Assemblywoman Fiona Ma, citing concern about global warming coupled with the rising cost of gasoline-dependent auto and air travel. As chairwoman of the legislative High-Speed Rail Caucus and one of the project’s two chief legislative advocates, Ma is actively recruiting support. “As I’m going around the state, people are sick and tired of sitting in gridlock and going to the airport two hours ahead of time,” Ma said. “I think voters will pass this overwhelmingly.”

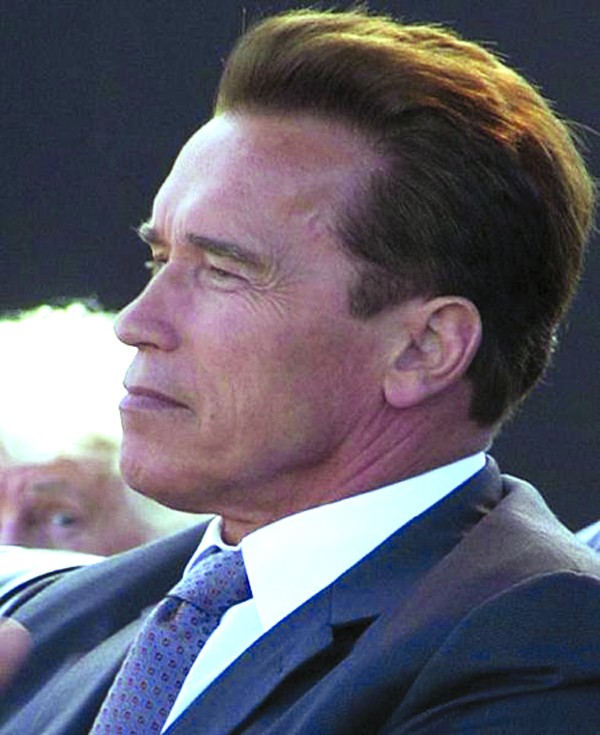

Yet reaching that point will be a challenge at best, and a series of obstacles could derail the train. In addition to the predictable disagreement over who should foot the bill, rail proponents have repeatedly criticized Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger for professing support while actually doing his best to keep Californians from voting on the project. This year could be Schwarzenegger’s last chance to demonstrate that his support is genuine.

Meanwhile, now that organizers have favored a Bay Area route through the Pacheco Pass east of Gilroy instead of through Altamont Pass and the Tri-Valley, the project faces another potential snag. A coalition of state environmental groups, some of which have been vocal supporters of the rail project in the past, claims that the Pacheco route would destroy protected wetlands, and is now threatening a lawsuit that could kill the bond measure altogether. To at least one project backer, these opponents can’t see the forest for the trees.

Who ever said building a railroad was easy?

“It’s a very difficult undertaking, but at the same time, this is a great project,” said Dan Leavitt, deputy director of the California High Speed Rail Authority, the agency charged with designing, constructing, and operating the system. “It could make California a much better place to live. Hopefully we’re in a situation when stars may be aligning. … But if we lose the opportunity that’s there now, it won’t be easy to do it again.” For every year of delay, he added, land prices and material costs rise significantly, adding billions to the final tab.

The project’s statewide environmental impact report was certified in 2005, giving the green light to proceed with engineering studies. The report encountered no opposition from any major state environmental group — a rarity for such a massive study — largely because the proposed routes are mainly planned along existing transit corridors and generally avoid environmentally sensitive areas. Virtually all of the system’s thirty stations are slated for downtown areas, a proposal meant to reduce sprawl and encourage sustainable transit-oriented development in California’s many languishing city centers.

But the Sierra Club and a number of other powerful environmental groups including Audubon California, the Nature Conservancy, and the National Resources Defense Council are less supportive about the authority’s most recent environmental impact report, which focuses specifically on entry into the Bay Area and favors the Pacheco Pass alignment, which would make for a speedier route from San Francisco to Los Angeles and also would be cheaper to build. That route would go from Los Banos in Merced County to Gilroy before heading north to San Jose and up the Peninsula to San Francisco along the CalTrain right-of-way.

“We think this report is fatally flawed,” said Bill Allayaud, the Sierra Club’s state legislative director. “There’s a bias toward the Pacheco Pass in the way they account for ridership and … environmental impacts.”

Allayaud alleges that politics, rather than sound science, influenced the decision; Silicon Valley, which would be directly serviced, lobbied hard for the southern route while communities in the Tri-Valley fended off the Altamont Pass, not wanting the railroad in their backyards. He believes it makes far more sense for the train to go through the Altamont Pass’ already urban corridor. Although little-known, he said, the other route goes through some “of the most pristine and important wetlands left in California.” Specifically, it bissects the Grasslands Ecological Area, which, at more than 90,000 acres, is the largest contiguous block of wetlands in California and a wintering area for more than 1 million birds in the Pacific Flyway. Located about fifteen miles north of Los Banos, the area boasts uncommon types of freshwater wetlands and native grasslands, supporting more than 500 species of plants and animals, some of which are endangered or threatened. While the Altamont route also would interact with protected wetlands — the South Bay’s Don Edwards National Wildlife Refuge — the coalition believes the environmental impact would be far less harmful.

In the strong likelihood that the rail authority’s board votes to certify the environmental impact report in March, Allayaud’s coalition has thirty days to file a lawsuit, something it is seriously considering. “Pick the wrong route and we’re going to have a train wreck,” he said.

For Mehdi Morshed, the rail authority’s executive director, a lawsuit is just par for the course for a project of this magnitude. “It’s highly unlikely there won’t be some kind of lawsuit,” Morshed said, noting that there has been serious consideration of eventually building a slower commuter rail through the Altamont into the East Bay. “No matter what decision we make, someone’s likely to be unhappy.”

The authority has been working closely with its legal counsel and the Federal Railroad Administration, both of which say the decision is defensible. The authority notes that the Altamont Pass route would be far more costly because it would involve the construction of a new Transbay Tube or bridge and potentially limit capacity while possibly also resulting in highly controversial eminent domain actions in the Tri-Valley communities in order to make way for as many as six tracks. The authority says this many tracks would be needed there to enable connections to regional rail services including BART and ACE.

Morshed said the Pacheco Pass decision just made more sense, even if it’s not perfect. “If environmental groups intentionally try to harm the rail … that’s their prerogative,” he said, suggesting the alternative would be more sprawl and roads. “If one route caused them to torpedo the whole project, would that be better for the environment?”

Cost and route aside, even the most ardent small government advocate would be hard-pressed to come up with a compelling argument against the benefits of high-speed rail in the state. California is the world’s twelfth largest producer of greenhouse gases. By 2030 its population is expected to increase 30 percent to 50 million people, far exceeding the capacity of the state’s already congested highway and airport networks.

Under the proposed 700-mile rail network, bullet trains would cruise from Sacramento to San Diego, hitting key metropolitan areas in the Central Valley, Orange County, and Inland Empire. A ride from San Francisco’s TransBay Terminal to Los Angeles’ Union Station would cost roughly $55 and take about two and a half hours. LA to San Diego would take one hour and fifteen minutes, and it would be under an hour from Sacramento to San Jose. The system also would service most of the state’s major airports and link to already existing regional rail networks. Following completion of the San Francisco to Anaheim route, the project’s extension to Sacramento and San Diego would take an additional four to five years with adequate funding, according to the authority.

Once built, the authority estimates that the system would require no operating subsidies, even generating surpluses to the tune of $300 million per year. This assertion is based partly upon the track records of high-speed rail systems in Europe and Japan, most of which have been completely self-sufficient after initial construction costs. And, despite the shock value of its price tag, more than thirty years’ construction of the system would actually cost less than half as much to build as would expanded highways or airports needed to accommodate the same traffic levels, according to the authority. In fact, the agency’s implementation plan notes that one Japanese high-speed rail from Tokyo to Osaka generated enough of an operating surplus in its first decade to completely cover the costs of construction.

The authority projects that the system would have more than triple the energy efficiency in transporting passengers as air and auto travel, significantly reducing the state’s dependence on foreign oil. A ridership forecasting study estimates that, by 2030, the train would carry more then 100 million riders a year, save 22 million barrels of oil, and reduce carbon dioxide emissions by up to 17 billion pounds. It would run entirely off electricity and actually regenerate some of its own energy. There even has been consideration of installing windmills alongside certain routes, directly powering the system with renewable energy in a move toward zero-emissions.

In short, it would seem that the whole thing would be right up Governor Schwarzenegger’s alley. An environmental leader, he was lavished with global acclaim last year for championing and signing into law AB 32, a landmark piece of legislation mandating a 25 percent cut in statewide greenhouse gas emissions over the next fourteen years. More recently, he has faced off with the federal Environmental Protection Agency over California’s right to impose emission standards for cars and light trucks. Early this month, the state filed a lawsuit.

In recent public statements and editorials, Schwarzenegger has said he strongly supports high-speed rail. But he also successfully urged lawmakers to postpone the $10 billion bond measure when it was slated for the ballot in 2004, citing more pressing budget needs. In 2006, he again proposed shelving the rail measure to avoid competition with bonds that could fund his proposed Strategic Growth Plan for the state, which included zero funding for the project.

“I feel like a yo-yo, because every year we go through this cycle,” said Morshed, who by now is accustomed to his lack of job security. “One year we are up, one year we are down. When we are up, I expect a downside, but when we are down, I don’t always know if there’ll be an upside.”

David Crane is one of Schwarzenegger’s top economic advisers and his most recent appointee to the authority’s nine-member board. An outspoken free-market advocate, Crane has served as Schwarzenegger’s mouthpiece on the project, underlining the need to secure private-public partnerships and federal support. He argues that state, federal, and private sectors should all commit to contributing equally to the project before the taxpayers are asked to fork over any more dough.

“There is no question that California would benefit greatly from a network of high-speed rail lines connecting communities throughout the state,” Crane wrote in an e-mail interview. “The question is how to succeed in getting there. In our view, the chances of success are greatly reduced if voters are asked to approve or fund a bond without assurances that participation by private sector and federal partners is highly likely.”

The Schwarzenegger camp, which has repeatedly insisted on seeing a more comprehensive financing plan from the authority before committing any more of the state’s budget, initially proposed postponing the measure once more in 2008, according to Assemblywoman Ma. Recently, though, Schwarzenegger’s stance has been markedly more nebulous. According to spokeswoman Sabrina Lockhart, he “has not taken a position on this particular issue.” Ma says the recent shift in rhetoric is a clear result of pressure Schwarzenegger feels from mounting statewide support. One instance occurred last July, when the Fresno Bee accused him of “photo-op environmentalism,” lambasting him for failing to adequately fund the project. The editorial came out just two months after Schwarzenegger wrote a letter for the same publication extolling the virtues of high-speed rail in California, pending private partnerships.

In short, it’s the classic example of a public infrastructure project that everyone likes, but no one may be willing to support.

Things looked particularly bleak for the project in the heat of last summer, as legislators engaged in what seemed to be an infinite battle over the state budget. The authority optimistically requested $103 million toward further engineering and design. Schwarzenegger, however, offered just more than $1 million. For a massive public infrastructure project, that’s tantamount to contributing about four bucks to your kid’s Ivy League college fund.

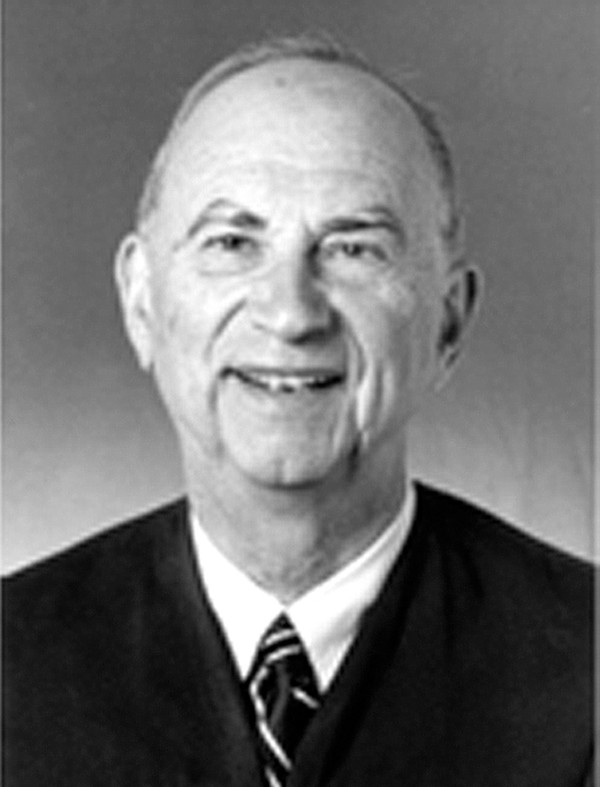

“If that had occurred, I would have resigned and recommended to the legislature that it shut down the authority,” said Quentin Kopp, a retired judge and former state senator whose legislation established the authority and who now serves as board chairman. In the end, the legislature allotted $20.5 million, enough to at least keep the torch burning.

“We realized he was trying to kill the project, that he had other priorities like jails, water, and healthcare,” adds Assemblywoman Ma. “If he’s the ‘green governor,’ what better way to meet AB 32?”

Part of the uphill battle in gaining political support in Sacramento is the project’s long time span. In 2006, Schwarzenegger even referred to the project as “visionary … but far in the future.”

Kopp notes: “Politicians, you will find, have very short outlooks on life. If a politician figures he won’t be there to break ground, interest declines.”

While eager to ride the train in his own lifetime, Kopp said he isn’t daunted by the lengthiness of the process, noting the enormity of the task at hand. After all, BART, a model train set compared to a statewide system, took nearly twenty years to get from initial study to implementation. Kopp, who recently sent the governor a letter inviting him to co-chair the bond measure campaign, is optimistic it will make the ballot, noting that Assembly Speaker Fabian Núñez has committed to ensuring it remains as is, which would mean that only a two-thirds vote from both houses could remove it.

If voters approve the bond measure, Kopp adds, the floodgates could swing open, ushering in private investment and federal matching funds. The authority already has begun interviewing a slew of financial funds that invest in transit projects.

Like most high-speed rail advocates, Kopp agrees with Schwarzenegger that public-private partnerships are essential to funding the project. In particular, he believes the system should be privately operated, to help relieve California of economic responsibility for the rail after initial construction. He believes a logical candidate for such operation would be Southwest Airlines. Kopp points to several regular rail lines in Europe that have been successfully operated by private airlines, including the UK’s Virgin Rail.

Southwest Airlines certainly would have incentive to care about high-speed rail in California. The airline currently runs almost hourly flights from Los Angeles and San Diego to the Bay Area, and some project advocates worry that it will try to destroy any potential competition. That was the case in 1991, when Southwest waged legal war against a proposed high-speed rail connecting San Antonio, Houston, and Dallas, effectively killing that project. But Kopp notes that many airlines are now shying away from such often-unprofitable short-distance flights in favor of more lucrative longer routes. Still, the California authority has yet to hear a peep from Southwest, which did not respond to repeated interview requests for this article.

In spite of Kopp’s support for private operation in the long run, he argues that state government has to be willing to make the first move. If it doesn’t, he believes, nothing will happen, and private investors will be unlikely to commit support to a project of this scale that hasn’t first won public support. A perfect example is the financing plan that Schwarzenegger wants to see before supporting more funding. Morshed says such a comprehensive plan is only possible after more engineering and environmental work has been done, and that is only possible with more funding.

“The governor has stated many times that he favors the development of high-speed rail in California,” said Congressman Jim Costa, a Fresno Democrat who has sought federal funding for the project. “However, it is extremely counter-productive to cut funding to the agency which has laid the groundwork. Since this is a state project, the governor needs to … take the initial lead on funding high-speed rail. The federal government will then assist with this project, as they have with many other major infrastructure projects.”

Elected officials feel little pressure from the public to make this thing happen because most Americans have no concept of what high-speed rail is, said Stuart Cohen, executive director of Transportation and Land Use Coalition, an Oakland nonprofit agency that has worked with the project. Many think of long-distance rail transportation as waiting for hours for Amtrak, the nation’s antiquated and economically bereft train system. “It seems like a fantasy,” he argues, “but in other countries, like France and Japan, it’s just the way people get around.”

Indeed, the United States is one of the world’s few industrialized nations with no real high-speed rail system. (The Amtrak Acela, which runs along the Eastern seaboard, is sometimes called high-speed rail, but its top speed of 150 miles per hour is significantly slower than that of true high-speed rail systems.) Japan led the way, and began operating its first of many trains in 1964. In much of Western Europe, high-speed rail has become a simple fact of life, and Assemblywoman Ma called attention to its ubiquity last year when she was on a test ride of a French train that set a new speed record of 357 miles per hour. China recently built a magnetic levitation train from downtown Shanghai to the airport, and now a number of other developing countries are planning their own systems, including Turkey and Mexico, which is designing a route from Guadalajara to Mexico City. It’s proven not only to be the safest transportation system, but by far the most efficient, rarely requiring government subsidies after initial construction and, in many instances, gaining net revenues.

Of course, most of these countries are more mass-transit-oriented and have higher population densities, two major precursors for strong government support of rail projects. But some argue that California will soon be just as crowded.

While few question that Schwarzenegger is justified in demanding a sound financial plan for the project, some rail proponents point to major inconsistencies in the governor’s transportation-funding decisions. “We’re subsidizing mobility all the time,” Cohen said. “It’s quite a double standard to say this project needs to find other money.”

He points to the 2006 election, in which Schwarzenegger successfully campaigned for Proposition 1B, a $20 billion transportation infrastructure bond, the largest ever considered in California. Intended to reduce congestion in the state, 50 percent of the pot goes to highway construction or expansion. Money will be repaid over thirty years by drawing from the state’s General Fund.

While the high-speed rail system’s projected $40 billion price tag is the biggest point of resistance, Cohen argues that highway and airport expansion projects often end up costing much more in the long term since they remain infinitely dependent on continued subsidies. For instance, he notes that just expanding Highway 99 from four to six lanes, a project earmarked in last year’s bond, will cost $6 billion. And that does not include the hidden environmental costs of higher emissions and more sprawl.

“High-speed rail is seen as expensive, but it’s cheaper than building roads to move the same number of people,” Cohen said. “It’s a larger failure of the people of California and legislators to have a vision of what we want twenty to thirty years from now. We’re going to pay for mobility one way or another.”

Cohen asserts that without high-speed rail, mobility in the state will soon be severely impaired. He remains cautiously optimistic that this year the project will get the boost it needs, especially if the public is adequately educated about the issue. But there are still strong opposing forces.

“The deficit will give some cold feet about infrastructure investment,” he said. “On the other hand, the global warming issue is rising in importance by the day, and this achieves dramatic greenhouse gas reduction. We have to see which of those forces is stronger.”