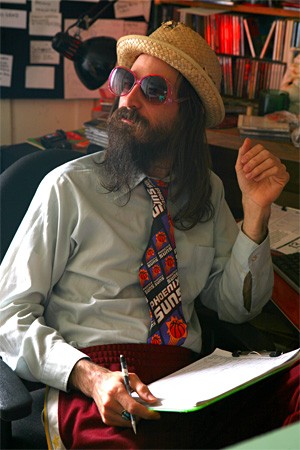

The gallery at 111 Minna teems with hipsters and yuppies slurping beer, laughing aloud, and making small talk over the blare of punk rock. In walks Oakland artist Brian Brooks, with long, stringy brown hair and a kinky six-inch beard. He is looking for a place to hide.

“The art thing is for a very small group of people,” says the rail-thin 35-year-old. “It’s for the artists and the hipsters. It’s a lot of schmoozing and looking over your shoulders and watching what other people are wearing. I stopped caring what other people were wearing a long time ago.”

Ten of Brooks’ most recent drawings of the cartoon character Emily the Strange — a sullen thirteen-year-old girl who has become an international icon of rebellion for girls and women — hang on the wall of this SOMA gallery. From 1999 until 2006, Brooks was one of the primary artists behind Emily, and an accessory to her current fame. Emily T-shirts, handbags, camisole sets, and other merchandise now sell in 35 countries. European high fashion designers have based clothing lines on her, and stars, including Courtney Love and Julia Roberts, have been known to wear her.

At least fifteen artists have collaborated to create the Emily brand, either as employees or freelancers of Cosmic Debris, the Emeryville-based design house that owns Emily. But as the first artist assigned to work on Emily full-time, Brooks shaped her more than most. The show at 111 Minna features renditions of Emily by Brooks and twenty other artists. But his drawings are the most bizarre, colorful, and eye-catching images exhibited. In one, Emily wears a Jerry Garcia wig and beard and leads three of her signature kitties — costumed as aliens — through a barren landscape. She strides high and long as in the famous Robert Crumb drawing Keep on Trucking. Brooks calls the 15 x 13-inch piece Friend of the Devil, after the Grateful Dead song.

Viewers give Brooks’ piece an approving nod. But only part of him wants to be at this art opening. That’s the part of Brooks that craves recognition and takes pride in the hundreds of designs he created when he was an artist and art director for Emily. The other part is a recluse who abandoned his catbird’s seat after 20th Century Fox began developing a movie about Emily.

Fox optioned the rights to a movie for an undisclosed sum in 2004 and is scheduled to either develop the movie or return the rights to Cosmic Debris by the end of the year. If Fox makes the movie, Cosmic will get another undisclosed sum, but Brooks won’t be owed another dime.

“I don’t want to be known as the Emily guy,” he says. “I’m very proud of what I did with Emily. But I don’t want that to be on my epitaph.”

Brooks slaved over Emily for fifty to sixty hours a week for six years. To fulfill his duties as an artist and art director at Cosmic, he felt like he had to forego his personal creative vision. He reaped a large enough fortune during those years from Emily and another character he created for Cosmic to avoid working for the past year and a half. But just as Emily was about to make Cosmic really rich, Brooks let go of her coattails. He wanted the world to know that he is an artist who deserves recognition independent of Emily the Strange.

So there’s more than a little irony to Brooks’ first art show in ten years being all about Emily. He agreed to the exhibit because it would give him a chance to show that he’s grown as an artist since leaving Cosmic in February 2006 and retreating to his dingy Shattuck Avenue flat. To cope with his uneasiness, he plays the jester, an appropriate role considering his mélange of clothing. A maroon wool scarf hides beneath his hair and under the two jackets he wears. A red fanny pack girds his waist. Silver earrings dangle from his ears and a set of beaded bangles covered with brass charms dangle from his left arm.

The DJ, Noel Tolentino, a New York-based former Cosmic artist who helped Brooks land the gig drawing Emily nearly eight years ago, comes over to say hello. He tells Brooks that he’s moved in with his girlfriend.

“Are you getting some sex?” Brooks asks.

“Yeah, online,” Tolentino says.

“www. what?”

“www.meandmygirlfriendhump.”

“Well is it .com or is it .org?” Brooks asks.

Brooks never wanted to work as a nine-to-five artist, or a nine-to-five anything. As a twelve-year-old growing up in Phoenix, Arizona, he idolized George Harrison of the Beatles and punk bands such as the Toy Dolls, who urged rebellion against bourgeois ethics.

Under Harrison’s influence, Brooks got his hands on a copy of the sacred Hindu text the Bhagavad Gita and, after reading a few pages, concluded that Krishna requires his followers to renounce their worldly possessions. Brooks loved his budding collection of Beatles and punk rock albums too much to become an ascetic. But as early as seventh grade, he knew he never wanted a job. “The adults would say you’re going to be an architect,” Brooks said. “It just didn’t sound right. At twelve I thought I was going to make a career of [art] and make a living out of it.”

At the end of ninth grade, he dashed his parents’ hopes that he would ever become a doctor, like his father, or a teacher, like his mother. That’s the year Brophy College Preparatory, his rigorous Phoenix Catholic school, expelled him for flunking every subject but P.E. and Algebra, which he mysteriously passed with a C+. At his new public high school, he dropped all his advanced placement classes so he could hang out with the hip kids.

Brooks’ transition from smart rich kid to social misfit coincided with his transition from casual to serious artist. While his grade school classmates played with their friends, Brooks spent most of his evening holed up in his bedroom, drawing. When he was twelve, he created a fictitious company called Brooks Publishing Limited to handle his fictitious affairs. “There were no requests coming in,” Brooks said. “I’d take the art around to my two brothers and my mom. I had an audience of three.”

He didn’t have much to say when he was twelve. But even then, he began a cartoon series called The Family that foreshadowed his future as a satirist. The Family was a more-disciplined and rigid Chinese-American version of his parents and two brothers. The kids went to bed at 7 p.m. in the summer and the dad followed suit within an hour. The dad resembled Brooks’ own hardworking father, whom Brooks felt never knew how to relax. “I’ve always seen him as Chevy Chase from Vacation,” Brooks said. “Very nice, but not very real-worldish. Every time we went somewhere, we were embarrassed.”

Though Brooks didn’t want to ever get a job and barely acknowledged that he was in high school, he wasn’t a slacker. In his sophomore year, he started staying up until 2 or 3 a.m. practicing his drawing techniques. He soon stopped sleeping on a normal schedule. Some of his pieces were so intricate that he would spend one week on them. His art teacher created an award to recognize his talent and work ethic at his senior year awards ceremony. By the end of high school, he had a file cabinet containing more than 2,000 chronologically organized drawings.

When Brooks graduated from high school, his parents pressured him to attend community college. So he began taking art classes and general education classes. “It was just a place where I could fend off the future,” Brooks said. “I was just going with the flow.” Then his father suggested he apply to art schools. His dad had to escort him on a campus tour. At first, Brooks didn’t understand the value. “I was already an artist in my head,” he said. “I knew that real art got done at home.”

But when he enrolled in the San Francisco Art Institute, he got wings. There, he focused on printmaking. More importantly, he became aware of conceptual art. That’s when he began focusing on bugs, sadness, and atheism — three subjects that persist in his work today. His pieces became more intimate and emotional. The characters seemed to talk to each other and each of his drawings began to tell a story. He also became a master at evocative detail. One drawing he did in college is a color-by-numbers scene of Jesus being carried off the cross. Under his loincloth, Jesus has a boner.

Brooks’ father paid for art school, while Brooks worked on campus to make some extra cash. But during college he never thought about how he would make a living. “I knew once you got to a certain point, you wouldn’t have to worry about money,” he said. “I just knew it was gonna work. I didn’t question it.”

After school he got a temp job stuffing envelopes at the Names Project Foundation, the San Francisco nonprofit that oversees the AIDS Memorial Quilt, and another temp job at an architect’s office. But every other month he asked his dad for money.

Graduating from college was a big letdown for Brooks. He lost his access to the screen printing room, his meager community of friends, and his sense of direction. He disliked his life in San Francisco so much that when he went to his younger brother’s graduation from Boston University in 1997, he decided to move there. Six months later, he was sleeping on the couch in the house his brother shared with five friends and recycling beer cans to get $7 or $8 a day for cigarettes and food. It was one of the happiest times of his life. “It was wonderful,” he said. “I just had so many friends. I was hanging out in book stores. Going to New York.”

His dad sent him a check every month. And he got a few temp jobs catching bound paper or T-shirts coming off of large offset printing presses. But blue-collar labor ill-suited him. One screen printing company fired him for ruining six of their industrial screens. He failed to wash the emulsion off their screens because the washroom was occupied when he needed to use it. Another reprimand came from a book store where Brooks worked. His boss wrote him up for jokingly telling a co-worker that he ran the Boston Marathon the previous day. Her write-up said Brooks was untrustworthy.

A year into this drudgery of petty jobs and temp work, in 1999 Brooks got a call from Rob Reger, one of the owners of Cosmic Debris. Brooks and Reger knew each other from the San Francisco Art Institute, where Reger was a teaching assistant for one of Brooks’ classes. Brooks’ work ethic and weird sense of humor had impressed Reger. “We communicated,” he said. “We liked all the same stuff.”

One of Cosmic’s employees, Noel Tolentino, suggested that Reger consider hiring Brooks to work on a new brand that Cosmic wanted to refine, Emily.

The character — a thirteen-year-old loner with black hair and pale skin — was in the developmental stage, with only eleven drawings. All of them were red, black, and white, and in all of them, she appeared inside a frame. Each image was accompanied by a clunky phrase like “Emily did not search to belong. She searched to be lost.” And her bangs had a shine that made her look like a bird had pooped on her hair, Reger said.

Though rudimentary in concept, the brand had potential. Between 1992 and 1998, some boutiques in Santa Cruz and San Francisco bought and sold Emily T-shirts. Then in 1998, Reger and his business partner, Matt Reed, secured a distribution deal with Hot Topic, an up-and-coming mall chain that specialized in music-inspired accessories for teens. That same year, the Los Angeles Times did a story about Cosmic, and Hollywood producers began calling Reger to ask about Emily’s backstory and find out if the company was interested in a movie.

Hot Topic carried the Emily brand in its first eight stores and continued to add her as its empire grew to almost 600 stores in 2004. The Hot Topic deal flushed Cosmic with cash, and Reger and Reed decided to hire an artist to flesh out the brand and churn out designs. Reger picked Brooks. Initially the job was part-time and paid $11 an hour.

Brooks took the job, thinking he would only work for Reger for three months, then head back to Boston with a stash of cash. While shopping with his mother, he had seen an Emily notepad at a Hot Topic store in Phoenix. “I knew she was becoming a cult thing,” Brooks said. “It was a proud moment. I told my mom that I knew that guy.”

Brooks moved to Oakland, into a flat in a cold, dilapidated Victorian on lower Shattuck Avenue with two of his best friends from high school in Phoenix. Almost immediately, he went to the Temescal Library, which was operating out of a dreary temporary storefront at the time, to practice drawing Emily.

One of the first changes he made was to blacken the white background in which Emily always appeared. Next, Brooks changed Emily’s clunky catchphrases into clever remarks. Where earlier designs used multiple sentences to describe Emily, Brooks sometimes used a single word: “Strange.”

Brooks also gave Emily a feisty attitude and rock ‘n’ roll credibility. His first blockbuster design was Emily drawn with her arms folded like Uncle Sam saying, “I Want You to Leave Me Alone.” That one sold 5,000 T-shirts. “That was one of his early designs that struck a chord and gave us this attitude that empowered the wearer to not just be saying something about the character, but something about themselves,” Reger said.

Brooks’ other drawings used as slogans song titles like “Too Much to Dream,” “Mommy’s Little Monster,” and “See Emily Play.”

He quickly lost sight of his plan to leave Cosmic in three months. “I was so excited because it was growing so fast,” he said. He began working fifty to sixty hours per week, releasing drawings four times per year, during each clothing season. At first, Emily only appeared on totes, stickers, shirts, and socks. But as Cosmic secured licensing, manufacturing, and distribution deals with other companies, the line expanded.

In 2000, Cosmic signed a deal with Chronicle Books to do one Emily book and four stationery products that led to three more books and eight more stationery products. The Chronicle Books deal introduced Emily to mainstream book stores and international readers. Cosmic began taking Emily to international trade shows. The same year, the company opened an Emily store in Tokyo. Emily became so popular that in 2005, the Damned, a British punk band, asked Cosmic to do a cover for their single “Little Miss Disaster.” Brooks drew a windswept Emily, in her characteristic black, white, and red.

Brooks was Emily’s primary artist until the company hired someone to help him in 2002. The same year, Reger promoted Brooks to art director, the post he held until his departure. In that role, other artists typically drew for Brooks. He came up with ideas and snappy lines and oversaw their designs and the merchandise to make sure it was consistent with the Emily brand.

“Brian’s contribution was not just art,” Reger said. “It was also spirit and character. He was a genuine weirdo in a company of everybody being individuals. He embodied a spirit that kept things alive and kept things interesting. There was no limit to his ideas and imagination. He would go home and work for hours and hours.”

For his first five years at Cosmic, Brooks was thrilled. “I was doing what my idols were doing,” he said. “It was like I had several hit records.”

Until about 2001, Cosmic gave Brooks bonuses when Emily’s sales jumped. And even after 2001, he received many raises. But the more Brooks gained Reger’s confidence and rose in seniority, the unhappier he became. The more he worked, the less time he had to explore his own creative interests. The one character that he created outside work became part of Cosmic’s brand portfolio when Brooks offered her to the company. Oopsy Daisy is an innocent preteen girl with a constant deer-in-the-headlights gaze who stays in trouble despite her best efforts to be good. Oopsy, not Emily, graced the front of Cosmic’s best-selling T-shirt. The shirt — “Oops, I said the F-word” — sold 50,000, many more than the best selling Emily shirt.

Other than Oopsy, from 2001 until 2005, Brooks didn’t produce any art unrelated to his job.

He had relied so much on the computer that he’d even lost his ability to draw by hand.

Brooks knew that Reger was working on a film and from time to time he even reviewed his scripts. But he had no interest in participating in the movie. What he wanted was to fulfill his own creative vision.

“To come home and read and write and think about Emily was too much,” Brooks said. “I was already working ten hours per day. I needed to come home, get loaded, and make strange drawings.”

In the fall of 2005, Brooks began to take back some of his life. One of his first steps was to turn the foyer of his flat into a private art gallery. On the weekends, he and his girlfriend, 29-year-old Emily Wick of Oakland, would get together to make art. Each Sunday at 6 p.m., they would sit down and talk about what they had done. Those private shows gave Brooks an incentive to produce.

Two of his earliest pieces were photomontages that revealed his angst over how much he worked. In one piece, he crouches on his hands and knees, bearing the weight of five more versions of himself on his back. Each version of himself stands for one year spent at Cosmic. Each year, he stands a little taller and straighter. The final Brooks holds a light bulb just under the socket of a light fixture in his kitchen. The bulb flashes brilliant and Brian’s eyes and mouth widen in Eureka, as he discovers that he must leave Cosmic.

In the other photomontage, there also are multiple versions of Brooks — one for each day of the week. Today’s Brooks is at the head of the pack, being shoved into work in his pajamas by the other four Brooks who are saying, “Go on!” “You can do it.” “Get in there.” And “We’re behind you.” Today’s Brooks looks dazed.

That fall, Brooks told Reger that he wanted to quit. Reger knew he was burned out, but asked him to stay a while longer to give the company time to prepare for his absence. “I became probably a little dependent on him,” Reger said. “His reliability and work ethic really dug into what he wanted to do.” After a five- or six–month delay, Brooks’ last day of work finally came in February 2006. In his first months as a free man, Brooks did not have a clearly articulated plan for how he would use his sabbatical or what he hoped to produce. All he knew was that he needed to work feverishly before his money ran out to turn the thousands of drawings and nearly a hundred books he had made before going to Cosmic into a source of income. And he planned to make that many more. If he failed, he would simply resume work on Oopsy Daisy, which he and Cosmic now co-own.

Brooks uses the living room of his dark three-bedroom flat as his art studio. The room is a dim cell cramped with desks, shelves, and dressers and festooned overhead with a web of wires rigged to pipe music from the studio into the rest of the flat.

Nearly every day, Brooks would start drawing after his 10 a.m. breakfast, skip lunch, avoid friends, eat dinner, chug coffee, and keep working until 5 a.m. Eventually, he became a hermit. He documented and analyzed his productivity in a massive spreadsheet. According to that, he has completed two art projects per week and created hundreds of 8-1/2 x 11-inch drawings in the past year and a half.

Twenty of them have been graphic novels. And he’s spent hundreds of hours developing thirteen separate web sites to showcase or archive his work, much of which can be seen at PillowGoat.com. But most of what he has produced in the past year and a half are sketches that he knows will never become a finished product. He also has a lot of finished products that are not commercially viable. For example, last year, he made a coloring book that shows how Paul McCartney would have intruded upon John Lennon and Yoko Ono if he had happened upon them during their infamous bed-in. The title of the book is One & One & One/is three. This summer, he made a coloring book called Jeff Lynne in Space, in which the 1970s rock singer’s gigantic Afro disrupts his fantasy space voyages.

Those books are part of a series Brooks calls Rock n’ Droll that he’s been working on for twelve years. But he doesn’t want to sell any of them because they use trademarked names and images and would be a lightning rod for litigation. He knows this because Paul McCartney’s attorney sent him a cease and desist letter in 1995, asking him to stop publishing the books Paul McCartney’s Hair, Paul McCartney’s Right Eye, and Paul McCartney’s Songs, and to pay them any money he had received. Brooks never sold any of those, so there was nothing to repay. “I lost money on the printing costs and I didn’t think it would be appropriate to bill them for that so I just dropped it,” Brooks said.

Brooks’ drawings of Emily also drew a few cease and desist letters — one from the rock ‘n’ roll poster artist Peter Max and one from the rock band Van Halen, who heavily influenced some of Brooks’ drawings. Cosmic pulled the offending merchandise from the shelves and paid whatever they owed in both cases. “You don’t want to fool around with that,” Brooks says.

Many of Brooks’ graphic novels are original and could become big sellers. But some don’t meet the standard of excellence that he set in his earlier, pre-Cosmic work. The narrative may begin with promise but falter quickly, or fails to ever stir interest. For example, the book My God tries to parody religious conviction by illustrating the blind adherence of believers to the requests and commands of a cry-baby deity named My God. But only one of the drawings in the narrative actually succeeds in depicting the folly of faith. In that one, a woman who is boiling her cat in a pot on the stove tells her husband that My God told her to do it. In most of the rest of the drawings, no one is following My God’s commands.

But several of his recent projects have been commercially successful, or just plain brilliant. Last year, he and Reger created a short pilot for an animated cartoon series called Boyz on da Run, which is about the fugitive life of a Backstreet Boys-like group that got caught lip-synching. Reger and Brooks created three episodes, all of which aired on the Disney Channel. Disney paid them a total of about $10,000 for the pilot, but did not turn the episodes into a series.

“I’m proud of it,” Brooks said of the pilot. “But I don’t want to make new ideas that Disney can own.”

The pilot retained some of Brooks’ quirky sense of humor, but lacked the intelligence and biting social commentary that are the trademarks of his best work. More representative of that is the line of holiday greeting cards he’s been working on. A card he made for Easter depicted the crucifixion with a twist. Rather than an adult Jesus, he drew a baby Jesus with a beard and pile of poop at the bottom of the cross. Behind the Christ stand two Roman guards. One leans toward the other and asks, “Did they say if we were supposed to change his diaper, while he’s still alive?”

So far, none of these good ideas has become a steady stream of income, but as ever, Brooks believes they will. So does Matt Reed, the man who was Reger’s business partner when Cosmic hired Brooks nearly eight years ago.

“I think Brian will continue to evolve,” said Reed. “As long as Brian continues to entertain himself, his results will be amazing.”

If Brooks hadn’t gone to the art show, he would have been in his dingy studio, standing up at one of his desks, drawing.

“I don’t want to take a day off to go drink beers at a gallery,” he said. “I could be working. I’m totally disconnected from the art scene and I like that. I don’t have to answer to what I’m doing or change what I’m doing for a lot of people.”

Until Reger invited him to participate in the show, Brooks hadn’t drawn a single Emily from the date that he left the company. “I needed to distance myself,” he said. “I needed to be Emily-cismed. That’s Emily plus exorcism.” But Reger’s invitation spurred Brooks to draw, color, print, and frame twenty to thirty copies of ten prints in the three weeks leading up to the show and make an appearance on opening night. His reasoning is contradictory: “I needed to get out of the house.”

Most of the collection in the show was black, white, and red, the colors of the Emily brand. Brooks’ drawings stand out because they also use blues, purples, and yellows, and put Emily in bizarre situations that make you cringe.

In one of Brooks’ drawings, Emily wears a Chewbacca headdress over a short purple dress and kneels next to R2D2, costumed as one of her signature kitties. Her knees are exposed, resembling beavage and a long phallic tail curves toward them. In the foreground, a miniature Princess Leia kneels with a headphone in her right hand. Brooks calls the 8-1/2 x 11-inch drawing The Message.

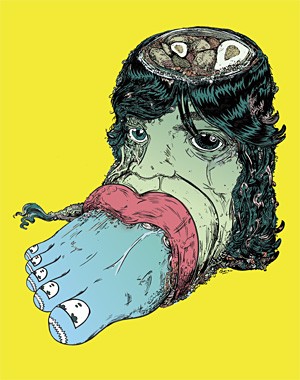

In Brooks’ most psychedelic drawing, a severed leg jams into Mick Jagger’s head and a wide foot protrudes from his mouth. On each toenail of the foot is Emily’s image. Brooks calls the 8-1/2 x 11-inch drawing Beast of Burden.

A 36-year-old software engineer who says she came to the gallery for the bar, not the show, says the Mick Jagger drawing is her favorite.

Her friend, a 38-year-old marketing manager, hates it. “It’s too disturbing for me,” says the frowning woman, who wears comfy sneakers and a hooded Yankees jacket. “I’m not into pop culture. Monet even bothers me. I want photographs of nature. I want peace.”

“But it’s funny!” the engineer argues, long dark hair draping her shoulders. “Look at it. Look at Chewbacca.”

For an hour, Brooks hugs the perimeter of the room, successfully avoiding hoopla. But when he moves to the main room to browse the work of some of the other artists, two female fans approach him and Reger.

The twentysomething goths have driven four and a half hours from San Luis Obispo to see the show. They toss their shiny, shoulder-length black hair seductively and press their lips together while Reger autographs a calendar for one of them. Then Reger passes the calendar to Brooks, flipping through the pages, saying, “There must be something in here you’ve done.”

Brooks says nothing, but finds one of his drawings in the calendar and, on top of it, superimposes two big toes that have been severed from their feet but are still in love. Both toes have googly eyes. The right toe says to the left, “I love you.” The left toe says, “You do?”

Brooks walks away from the grateful fans after signing the calendar, and the women confess they’ve never heard of him. They don’t even realize that he designed the images on the black Emily the Strange halter dresses and halter tops they’re each wearing.