Bitch bitch I ♥–%$#@ — hot bitch” is scrawled in white spray paint on the jungle gym at Richmond’s Elm Playlot. Used condoms and empty gin bottles lie beneath a slide, and two swings are frayed from canine tooth marks. The jungle gym is a sad focal point of the playground’s current role: as a gathering spot for pit bulls, drug dealers, and junkies.

Piles of broken glass and kitchen trash blight the adjacent neighborhood. Many nearby houses sport sturdy iron fences and grates or plywood on the windows and doors. People walking by contort their faces into guarded masks, and small children soon become authorities on needles and guns. More than 1,500 children under the age of six live within ten blocks of this corner at Elm Avenue and 8th Street, but they and their parents typically avoid this tiny park in Richmond’s notorious Iron Triangle.

Toody Maher had long dreamed of adopting a local park. Two years ago, she decided the time had come. Credits: Chris Duffey

In this aerial photo of the neighborhood surrounding Elm Playlot, abandoned homes are colored yellow. Credits: Toody Maher

The play structure at the Elm Playlot is tagged with graffiti on a weekly basis. Credits: Photovoice

Trash litters the yards of homes neighboring the park. Credits: Chris Duffey

Maher eventually convinced the Richmond Housing and Community Department to commit to purchase and rehab several abandoned homes in the neighborhood. Credits: Chris Duffey

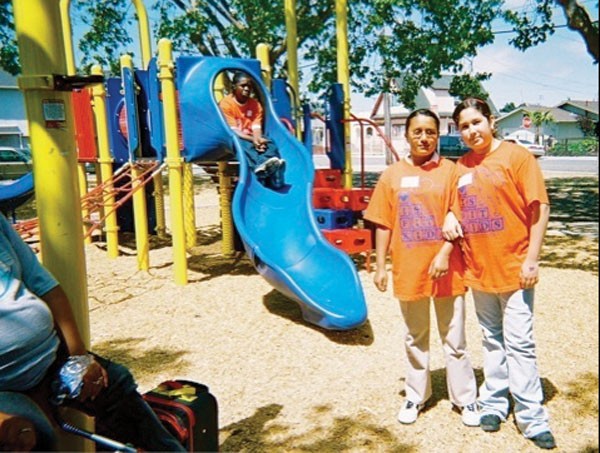

Area residents documented what they liked and disliked about their neighborhood in Joe Griffin’s Photovoice project. Credits: Photovoice

Area residents documented what they liked and disliked about their neighborhood in Joe Griffin’s Photovoice project. Credits: Photovoice

Area residents documented what they liked and disliked about their neighborhood in Joe Griffin’s Photovoice project. Credits: Photovoice

Area residents documented what they liked and disliked about their neighborhood in Joe Griffin’s Photovoice project. Credits: Photovoice

Area residents documented what they liked and disliked about their neighborhood in Joe Griffin’s Photovoice project. Credits: Photovoice

Area residents documented what they liked and disliked about their neighborhood in Joe Griffin’s Photovoice project. Credits: Photovoice

Maher reached out to community residents to discover why they weren’t visiting the park. Credits: Chris Duffey

It’s a rare person who can look at such desolation and see a patch of light. But Toody Maher is such a person. The tall, square-shouldered Richmond resident has assigned herself the seemingly hopeless task of rehabilitating the playground and resurrecting the community. Armed with an unwavering belief that every child deserves have a safe place to play, Maher hopes to revive Elm Playlot and renew the surrounding neighborhood in the process.

Maher’s own Canadian childhood was marked by long days at the neighborhood park, a safe, thriving centerpiece of her Montreal community. “Even in the middle of winter, my mom would give me and my three brothers and sisters breakfast, dress us in our snow clothes, walk us two blocks to the park,” she recalled. “Everyone who had children went there. It’s where friendships were formed, where parents met their closest friends. So much of our growing up was play, and we were never bored. I think that’s why I’ve always been magnetized to parks. Parks are power spots to me, and when I see them not reaching their potential, I can’t stand it.”

Today, at Elm Playlot, Maher is trying to create a similar space for thousands of deserving kids to play meaningfully. Her vision revolves around a radical idea she calls a “park host” or “play leader.” In thousands of European parks, a park host is a full-time job for trained professionals who create play opportunities for children while watching over their park. Studies indicate that play increases any time someone staffs a park, she says.

Maher vowed long ago that if she became wealthy she’d build a community playground and serve as its park host. “One day my partner said, ‘Why are you waiting to get rich?'” Maher recalled in an interview. “And I didn’t have an answer. My consulting contracts had ended, I had the time, and I thought, ‘Why am I waiting? I’m going to start building this playground, right now.’ It was the light-bulb moment.”

So in January 2007, she took action. For four months, she immersed herself in the city’s parks. She did some research and discovered that 22 percent of Richmond’s land area lies in 54 separate parks and eight playlots. The parks were there — but, by and large, the people weren’t. Maher learned where the new play structures were, and discovered how infrequently kids used them. She also went to parks that worked, and watched children play among groups of seniors gathering for tai chi classes. She began to imagine the mix of fixed and varied elements that she would build into her park: a bubble machine, an herb and butterfly garden, running water for streams.

“Everything in my work life has been about one thing: take an idea and make it happen,” she said. “So that’s what I’m doing: taking a run-down, seldom used, little neighborhood park and attempting to transform it into an outdoor play space where kids want to come to play every day.”

But can a well-intentioned white lady who lives across town from a tough inner-city park really make a difference? After all, Richmond’s own park improvement efforts had failed to make any real progress in many troubled neighborhoods. And ideas as radical and costly as a full-time park host or kid-sized teepees and streams were received with understandable cynicism when Maher first shared them. The money alone was daunting. She would need at least $400,000 just to think about her project.

But as Maher’s persistence slowly proved her mettle, the community’s initial skepticism began to melt. Little did neighbors know that making things happen is Toody Maher’s specialty.

Maher describes herself as an action-oriented, connect-the-dots kind of person. She is brimming with ideas and inspiration; words tend to spill out from her with a breathless quality made more endearing by her mild stutter. She’s the kind of person who instantly responds to e-mails at 10:30 p.m., and squeezes long thoughts into her text messages.

Yet straight out of UC Berkeley, she spent four paralyzing months climbing the walls in the backroom of a soulless Los Angeles office that sold bonds. Terrified of spending her life squeezing her size-twelve feet into stiff leather pumps and breathing recirculated air, she reached for an idea that would help her escape.

One year before, while playing pro volleyball in Switzerland, Maher had met the originator of Swatch. She saw potential in the plastic watches with bright wristbands, and believed they would take off in the United States. She began spending nights at the library reading up on how to craft a business plan, and eventually convinced the president of Swatch to meet her in Los Angeles to hear her pitch. In a bungalow at the Beverly Hills Hotel, Maher pitched her plan. Her earnest passion didn’t entirely sway the blunt Swiss president. “Your plan is bullshit,” he told her when she was done. “But I like your chutzpah.”

And so, at age 23, Maher had won the right to distribute Swatch in eleven Western states. Within three years, her sales had topped $30 million. Maher later moved on to start Fun Products, a Berkeley company that created the world’s first clear telephone. That emblem of the early 1990s, with its colored innards and flashing lights, was named Fortune magazine’s 1990 Product of the Year, and Maher was honored by Inc. magazine as its Entrepreneur of the Year. “I realized I was good at product sensing,” she said. “I knew what people wanted.”

Around the same time, she also began striving to give something back to her community. She worked with SF nonprofit JUMA Ventures to employ at-risk youth at ballpark concessions. And while working as a consultant for a UCLA research institute, she helped translate studies about children’s wellbeing into information easily usable by parents.

To Maher, it is only common sense that thriving communities and neighborhoods revolve around a nucleus of activity. But driving through the Iron Triangle, entire blocks suggest that people have lost hope. Elm Playlot is one such place. A semi-circle of empty benches faces the plastic play structure, and a concrete path cuts between untended grass and a groundcover of woodchips. Five massive and beautiful sycamore trees curve over the land, but beneath them lie dog feces and hypodermic needles. The colorful but unused play structure stands in stark contrast to its surroundings, a testament to failed good intentions.

Even if Elm Playlot were clean, Maher believes kids need a place that facilitates growth and the development of life skills. She calls this notion “meaningful play.” The concept is based on research that suggests how a child’s brain is hard-wired early in life. Research suggests that a child’s linguistic, social, cognitive, physical, and creative development — or lack thereof — is based on their early experiences. Through play, kids practice skills they will need throughout life. Waiting in line for the slide teaches social cooperation; building a fort develops cognitive skills; climbing up ropes strengthens physical acuity. When children lack a safe, stimulating place to play, they fall behind developmentally.

Middle- and upper-class families can inspire their kids with Gymboree, art classes, and lessons in the sport or activity of their choice. But in low-income communities, children are generally limited to playing at school and in their neighborhoods. And when those neighborhoods are dangerous, they’re more likely to fall behind or get into trouble. In her research, Maher encountered a study that suggests living in a blighted area is the equivalent to taking away a year of school.

In the emerging world of meaningful play, play leaders supervise and guide children in inspiring and ever-changing types of play. Research suggests that guiding children in free play by giving them the elements to built forts, create sandcastles, or just play hide-and-seek increases their development. Maher believes the most essential play element for young children is a simple sandbox stocked with buckets, shovels, and water. Yet cities have largely stopped installing them because of the hassle of cleaning and maintenance.

“The play leader concept is unheard of in this country because we don’t deeply value the environments we put our children in,” Maher said. “So we’re stuck in inertia. We bolt the same prefab jungle gym to the ground, over and over. We put costly play equipment in parks that people stop using over time because there’s no challenge involved. You go up, you walk across, you slide down. This isn’t unique to Richmond; every city in the country is putting up equipment that is sterile, static, and doesn’t fit in with the environment. For children to be able to grow and thrive, we must carve out safe, stimulating, and soulful places for them to play. We know this, but changing the way we do business is hard to do.”

Because Richmond’s eight playlots are located in the city’s densest urban areas, Maher concluded that they were in the direst need of help. She was immediately drawn to Elm Playlot, a corner lot easily accessible to children.

“When I started meeting with Toody, I told her that of all the parks, the one that needs her the most is Elm,” said Cheryl Maier, the executive director of the nonprofit group Opportunity West, which is involved with a four-year-old initiative called Building Blocks for Kids. “Toody is a dreamer and a pit bull rolled into one. She doesn’t take no for an answer, and she has made this park her full-time job. She has the time to be tenacious enough to see the right people. Can she do it? Yes, she is doing it.”

During the day, Maher would visit the park and sit there. But on visit after visit she never saw kids playing. She did see people running the stop sign on 8th Street, trash building up in driveways and yards, and abandoned houses falling into further disrepair. The park’s most frequent visitors were men drinking and shooting guns into the sky at night, and the bright play structure was tagged weekly.

Because the surrounding neighborhood was a microcosm of Richmond’s worst neighborhoods, Maher wanted Elm Playlot to be the first park she transformed. If her idea succeeded there, in the worst of places, she knew it would succeed elsewhere. So she started talking to neighbors.

Mother of four Carmen Lee was one of them. Lee, whose house on Elm Avenue is about ten steps from the park, is fed up with the neighborhood’s crime. “Too many people I know get killed here,” she said in an interview. “My friend got killed in the spring; a week before that happened it was someone else. Everyone’s dyin’ around here. It’s too easy for people here to get guns; they get ’em like you can get a candy bar. That’s the thing I hate. I hate that my five-year-old baby has to grow up like this, knowing about guns and death. She knows more about guns than I ever did. It’s just senseless.”

A safe gathering place is what many of Lee’s neighbors desire. “Hopefully the park will change things at least a little bit,” Lee said of Maher’s efforts. “There are a lot of people in the neighborhood I don’t know, and I have neighbors I should know. There’s a lot of separation around here, too much negativity. Maybe this park will be a place where we can get together.”

Despite the self-enforced racial segregation visible throughout the neighborhood, Lee’s comments highlight the tangible longing of the neighborhood’s largely black and Hispanic residents to connect. “The boot of circumstance is around people’s necks,” Maher said. But below the surface, she believes, people yearn for something better.

“One thing that surprised me about Richmond is that there’s a perception that it’s this blank slate of awfulness, when, in fact, there’s a world full of dedicated community activists working here,” Maher said.

People want to help Richmond, and people are helping Richmond. Community leaders, city leaders, and a few people with inexhaustible passion fight the good fight against a tide of crime and despondency. By infusing funds into schools and community centers, more and more good has been etched out against the city’s patchwork landscape. But as Maher would learn, there’s a long way to go.

When Maher first presented her concept of park hosts and play elements, she was met with cynicism. Her vision seemed like a big pipe dream for a place often so devoid of hope. At a community meeting on January 24, she got some skeptical looks and snickers at the mention of butterflies and bubble machines.

But in spite of all the snickers, it didn’t take Maher long to begin mobilizing people. She has gotten nothing but support from city officials, who already wanted to rethink their playlots but didn’t know where to start. They immediately agreed to her pilot plan, and she dived head first into meetings with city council members, budget analysts, the city manager, and anyone else who would talk to her.

“I started to see how the city was working and how things connected,” Maher recalled. “And when I went outside that circle of leaders and talked to people in the neighborhood, I really realized that so many people were in their own little bubbles. But I saw how we could work together if we all collaborated.”

In March of last year, Maher presented a 31-page park prospectus to the city and won approval to begin work to improve the park. After the city endorsed the reinvention of Elm Playlot as Pogo Park, Maher turned to the monumental task of fund-raising.

The city’s Redevelopment Agency took care of one major hurdle when it pledged 100 percent of the capital costs necessary to renovate the playlot, estimated at $400,000. Meanwhile, City Manager Bill Lindsey is committed to having the city’s Public Works Department coordinate street improvements around renovations of the playlot.

To redesign the park, Maher raised $37,750 from individual donors — an amount that was matched by the city and awarded to Urban Ecology, an organization dedicated to building ecologically and socially healthy cities. Many talented playground experts are lending their eye to the design of the park; including Ron Hothuysen and his Scientific Art Studio, which is responsible for the play elements at the Bay Area Discovery Museum and the huge baseball glove towering over left field at AT&T Park. As luck would have it, Hothuysen’s business is located in the Iron Triangle. With the help of Richmond residents in his employ, he is creating unique play elements for the new Pogo Park.

In fact, the city is seeking out local businesses to contract and build each and every park element, from the fence to the office. “We are right at the crest of doing something so different, in such a better way,” Maher said. “Everything will be local; people who live in the neighborhood will get the building contracts, bringing the money back to them. It is an instant economic stimulus plan.”

Urban Ecology has involved the community in the design of play elements and park layouts. Community members also will be hired for the park’s construction. Maher believes that the more threads that are weaved back into the neighborhood, the more chance the park has to succeed. If the park is designed by the mothers living down the street, built by teenagers whose little brothers will play there, and watched over by the grandmother who lives next door, the collective assumption is that people will be less likely to mess it up.

Playground designer Jay Beckwith, who is based in Sebastopol and is one of his industry’s most respected figures, is acting as Pogo Park’s advisor and planner. The California Endowment awarded $25,000 to the urban design and land planning experts at MIG, who are considering how to make the biggest possible impact on public health in the park’s design. To support educational programs at nearby Peres Elementary School that will mirror the programs at the park, the Irene S. Scully Family Foundation granted the project $20,000. And she convinced Kaiser Permanente to award $20,000 to support development of the play leader program.

But even if she managed to create a utopia among parks, Maher soon realized that Pogo Park alone couldn’t solve all the community’s problems.

During Maher’s many visits to 8th Street and Elm Avenue, she began to realize that the desolation of the surrounding neighborhood fed the problems afflicting the Elm Playlot. After all, the neighborhood surrounding Elm Playlot was a far cry from the one where Maher spent her own childhood.

Eight out of ten houses immediately surrounding the park sit unoccupied, serving as magnets for vandals and drug users. No one bothers to clean up the waste piled behind low front-yard fences. Keep-out signs and bright yellow auction notices are tacked over the plywood on windows and doors. The park’s shiny jungle gym is just a tempting beacon in a dangerous landscape.

So when UC Berkeley doctorate student Joe Griffin approached Maher with an idea for a project to document the decay and danger of park’s immediate neighborhood, she leapt at the chance to participate. Griffin, a native of Richmond, initiated his Photovoice project as a way to reach out to the community he grew up in. The project put cameras in the hands of Triangle residents and asked them to photograph what they liked and didn’t like about their neighborhood. The photographs were paired with their recorded observations to create a valuable illustration of life in the Triangle.

Many photographed the houses: “It’s not a good look for our daughters and sons to walk through and see where they live at. And when their teacher asks them, ‘Can you just draw us a picture of your neighborhood?’ they’re just going to draw old, rusty, broken-down, or undone houses that, you know, we cannot explain why this is happening.”

Others depicted the trash: “You look at a model of another neighborhood, and then you see your neighborhood. You see it as being hopeless. I mean, it’s not spoken, it’s just implied. Every day. But, we should just refuse to live like, you know, with something like this.”

Still others captured the Nevin Community Center: “I like this picture because these are all of my family members and … everybody’s in here doing something constructive. Just showing that people actually come here and do something, you know, it’s people that try to better themselves.”

Another celebrated a local community garden: “This is a beautiful community garden that the Iron Triangle has. I’d really like to see more gardens, more flora, in the city of Richmond.”

Maher used the project as a tool to bring more city officials over to her side. After Photovoice, she had a new bottom line: the park could only be safe if the immediate neighborhood was safe, too. The Redevelopment Agency agreed, and city Housing Director Patrick Lynch responded by pledging a portion of the city’s $3.6 million federal grant under the Urban Development Neighborhood Stabilization Program (NSP) to buy the abandoned houses that surround the park and remodel them into affordable housing.

“The NSP components will purchase and rehab blighted, foreclosed and abandoned properties and demolish blighted structures all in order to stabilize our most economically challenged neighborhoods,” Lynch explained. “Pogo Park is an excellent example of a neighborhood reestablishing families’ lives by merging supportive services with real property rehabilitation.”

There’s no magic wand to turn a vacant park in the middle of a low-income neighborhood into a safe haven for children and their families. The Pogo Park plan acknowledges what’s happening in Richmond and answers each challenge with a solution. For safety, install an attractive fence that will be open during the day and locked at night. For organization, build an office that will stock play supplies and healthy snacks. For meaningful play, provide children with a park host. To bring people together, schedule activities for children and exercise classes for parents.

“What started from a critical need to provide children with a place to play has turned into the catalyst for transforming the neighborhood,” Maher said. “My job is to create a safe place for kids to play and to become a link in this long chain of efforts by folks devoted to Richmond to make this a better place for everyone.”

Maher envisions the park as a gathering center for parents, and plans to offer outdoor exercise classes and monthly health clinics. She imagines it as a community hub, with visits from Richmond’s public bookmobile. She plans to work with teachers at Peres School to create activities that mirror and support what kids are doing at school.

“We want to have readings of books at the park that kids are reading in school, bridge some of the education through music that starts in school,” she said. “By tapping into the existing network at Peres, activities at the park will help get kids ready for school.”

With funding secured for the design and construction of the park, Maher is still seeking funds to develop, and operate Pogo Park. Chief among her needs are funds to support the play leader program and newly formed Elm Playlot Action Committee. The committee will consist of six neighborhood parents who will approve goings-on at the park, from the selection of the play leader to the choice of park activities.

Once Pogo Park is finished, Maher hopes to apply the same model to the city’s seven other playlots. She wants Richmond to prove that parks can be a catalyst for change and thus serve as an example to other cities with the same problems. To possibly justify the rehabilitation of more parks after this one, UC Berkeley’s School of Public Health will use a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to conduct a study that measures the impact of the revitalized playlot on overall community health. Maher hopes that the result of the study will eventually influence government policy surrounding funding for public parks around the country.

Nothing is fixed overnight, but if you obliterate the trash, drugs, and blight that stains a neighborhood, perhaps at least one corner of this troubled city will be on its way up. Groundbreaking for Pogo Park is on track for August, and with Maher’s heavyweight army of supporters to fall back on, all signs point to success.