I met Eli Horowitz in a charming cafe in San Francisco’s Mission district, where he’s lived for nearly eleven years. Out of guilt, I immediately admitted that I had used the cheat embedded in his and Russell Quinn’s newly released serialized story app, The Pickle Index, to consume the entire ten-day reading experience in one day. He chuckled and said, “I actually know that.”

Apparently, I was the first person to use the semi-secret feature, and the app had sent Horowitz an email notifying him not only that someone had figured it out, but that I, specifically, had figured it out. At first, I was alarmed — in an automatic, anti-surveillance kind of way. But Horowitz didn’t look like a malicious data voyeur (whatever those look like). Rather, behind his silver MacBook, he looked like a harmless artist, earnest in his overgrown beard and paint-covered hoodie.

Horowitz is accustomed to being met with technophobia. But the skepticism toward the tech industry and all of its consequences, which pervades contemporary Bay Area culture, is something to which he relates. After all, he served ten years as an editor and publisher at McSweeney’s — a San Francisco-based press known nationally for its indulgently nostalgic products of the paper form.

But while there, Horowitz also cultivated an interest in experimenting with presentation platforms, thinking about how to push the boundaries of storytelling by riffing on medium. His fascination with digital platforms is just an extension of that. “None of this stuff appeals to me because of the technology,” said Horowitz. “It’s not like I’m excited about phones. It’s just this thing that has certain possibilities that just open it up.”

Horowitz’ first serious foray into digital storytelling was The Silent History, a serialized novel released in daily segments via an app over the course of six months beginning in 2012. The award-winning novel also featured GPS-triggered portions that could only be unlocked at certain locations in San Francisco, where the story was set.

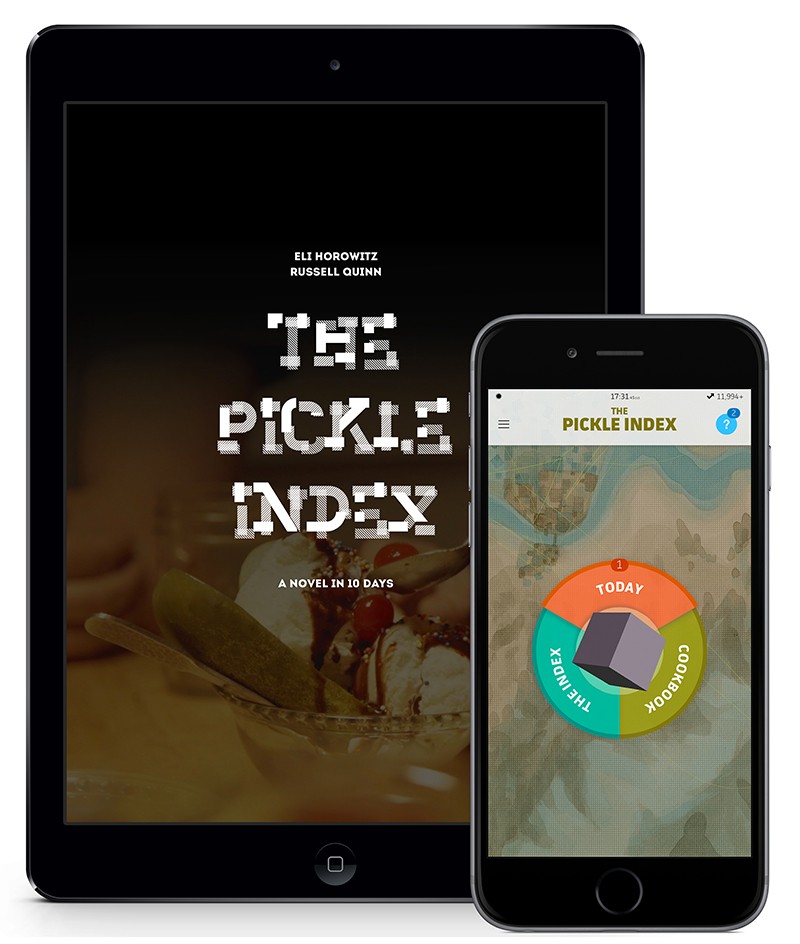

The Pickle Index is Horowitz’ shorter, more digitally interactive follow-up made in collaboration with programmer Russell Quinn. It’s set in a dystopian world where most of the population is forced to subsist off of pickles because fresh food is too scarce. To keep up morale, the government mandates that citizens consistently contribute inventive pickle recipes to “The Pickle Index,” a national, crowd-sourced database accessed through handheld devices called “scrollers.” The story follows a comically incapable circus troupe as its members attempt to rescue their ringmaster, who’s been imprisoned by the government. The $5 app has two primary narrative sources: daily, government-sponsored news updates, and diary entries from a circus member covertly written into recipes that the reader must retrieve from other citizens through the Index, which is visualized as a map — not unlike the Uber interface. Every day, for ten days, the reader receives one news report and is able to retrieve one new diary entry.

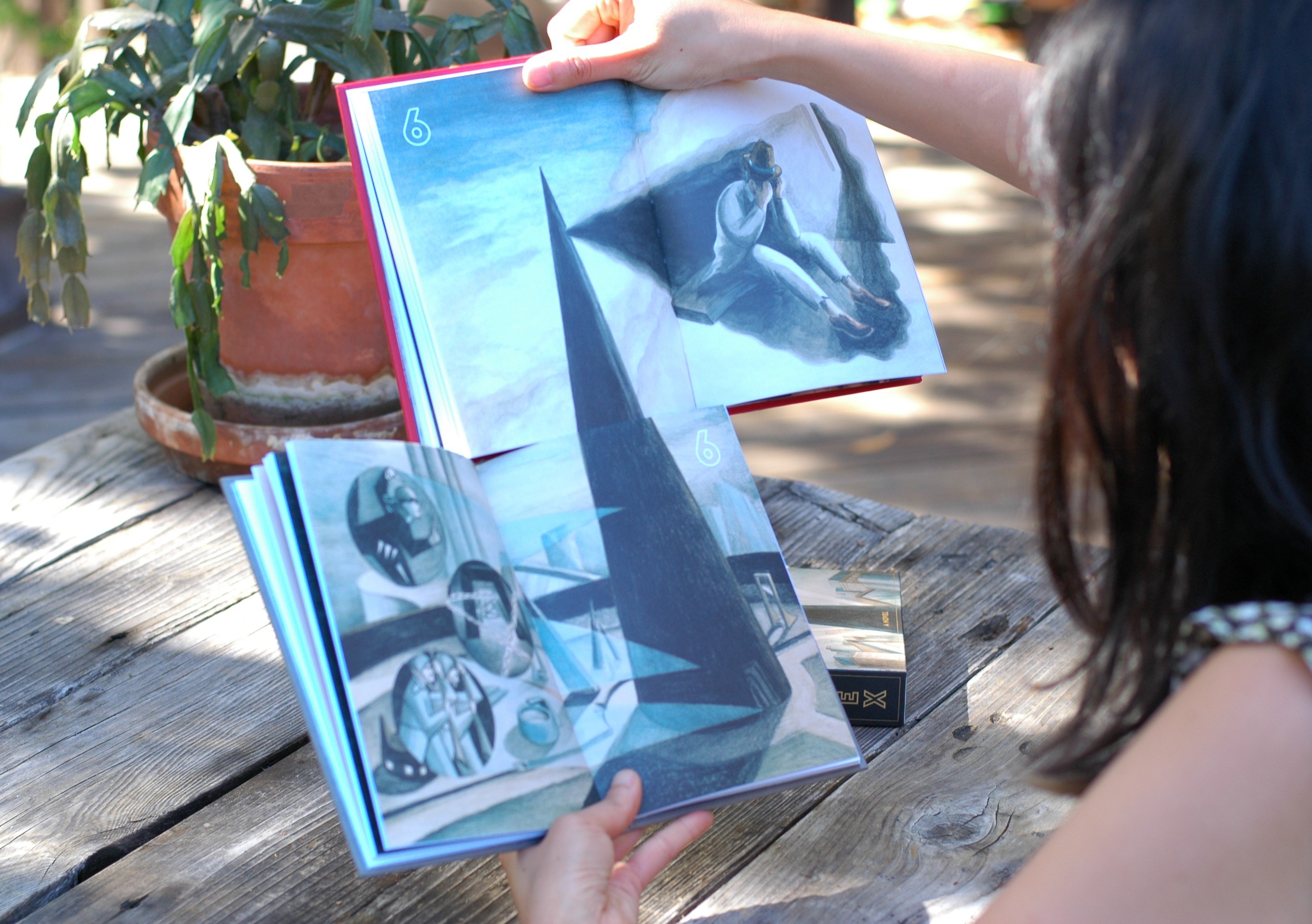

The Pickle Index also comes in analog form. Specifically, it can be read by alternating between two hard cover books (one with news updates, one with “recipes”). In both books, each daily segment opens with a retro-futurist illustration by Ian Huebert, which fits together with the illustration for its correlating chapter in the other book, like a puzzle piece.

Horowitz planned for the project to be published in both mediums from the beginning, and that’s crucial because it means that neither form was an afterthought. Rather than adapting digital content for print or vice versa, Horowitz and Quinn developed the two versions alongside each other, letting each learn from its counterpart. With both, they explore the relationship between interactivity and immersion, attempting to locate the sweet spot between narrative and game. While both versions evoke a similar sense of engagement as a game might, Horowitz was careful not to shift the focus away from the story. Rather, by delaying the reading process through serialization and required retrieval, he hopes to heighten the reader’s investment in the narrative.

In the mid-Nineties, when hyper-text fiction came on the scene, there was a bubble of excitement surrounding interactive, digital storytelling. It appeared as if modes of reading and writing were poised for radical transformation. But it pretty quickly became clear that the medium couldn’t capture attention the way many hoped it would, possibly because the kind of reading engagement it required was still too foreign. Now, reading novels digitally primarily means reading an e-book. With the technology we carry in our hands today, however, there’s almost overwhelming potential for new modes of storytelling that is barely being explored (outside the realm of indie video games), partly because a lot of the literary world would rather not play with fire at a time when the extinction of books appears to be an actual threat.

While Horowitz is aware of all that, it doesn’t dampen his eagerness for experimentation.

And he seems unfazed by the scarcity of successful precedents for this type of work. He likened designing the app with Quinn to building a cabin as a non-carpenter — putting pieces together and seeing if they fit. (That’s a real hobby of his). But that puzzle mentality is also likely the source of the book’s biggest downfall: The characters and storyline — while consistently amusing — are ultimately formulaic and lacking depth. It’s exciting to see the plot perfectly unfold as the blueprint behind the narrative is slowly revealed, but it’s a familiar blueprint from the start.

What’s most interesting about The Pickle Index is the sly critiques of tech culture that Horowitz appears to have planted in the story only half-consciously. In the novel’s fictional world, citizens get social media-like “citizen quotient” scores for using their “scrollers” on a regular basis — devices that are clearly fascist tools for keeping the population fooled and obedient. And when people are executed, the spectacular slaughtering methods are determined by crowdsourcing citizens’ suggestions — which all immediately become the intellectual property of the government once submitted.

But ultimately, Horowitz’ story maintains an underlying optimism about the democratic — even revolutionary — potential provided by technology. He began laying it out during the Arab Spring and was inspired by the use of Twitter as a tool for disseminating firsthand accounts of the uprising. Embedded in the platform of two storytelling sources, there’s an obvious critique of the omniscient government-sponsored media source, whose reporting gradually decreases in objectivity, yet, the recipe network offers an opportunity for citizens to communicate directly.

Throughout our conversation, Horowitz grilled me on my experience with the app. He asked why I was drawn to interact with it in certain ways, and how certain aspects made me feel. He’s interested, most of all, in the affective qualities of the experience. And although the prose isn’t stunning, the experience as a whole feels exciting. It’s even captivating enough to binge read in one day. Although you’ll have to be okay with Horowitz knowing.