There’s a timeline on the wall at Betti Ono gallery: On one end is 1991, the year that George Holliday famously filmed police officers beating Rodney King on the streets of Los Angeles. Next is 1992, the year that those same officers were acquitted and L.A. residents responded with riots. The morbid black line pushes through time, consistently branching off to blocks of text that memorialize lost Black Americans as it traces the perimeter of the gallery.

Names on the wall include unfortunate celebrities Oscar Grant, Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, Michael Brown — with many, many less recognizable ones between them. LaTasha Harlins, for example: the little-known Black fifteen-year-old girl who, two weeks after the King beating, was shot by a Los Angeles store owner, who suspected her of stealing. Although the shooting was caught on surveillance cameras, and the clerk faced up to sixteen years in prison, he walked away with just probation, community service, and a $500 fine.

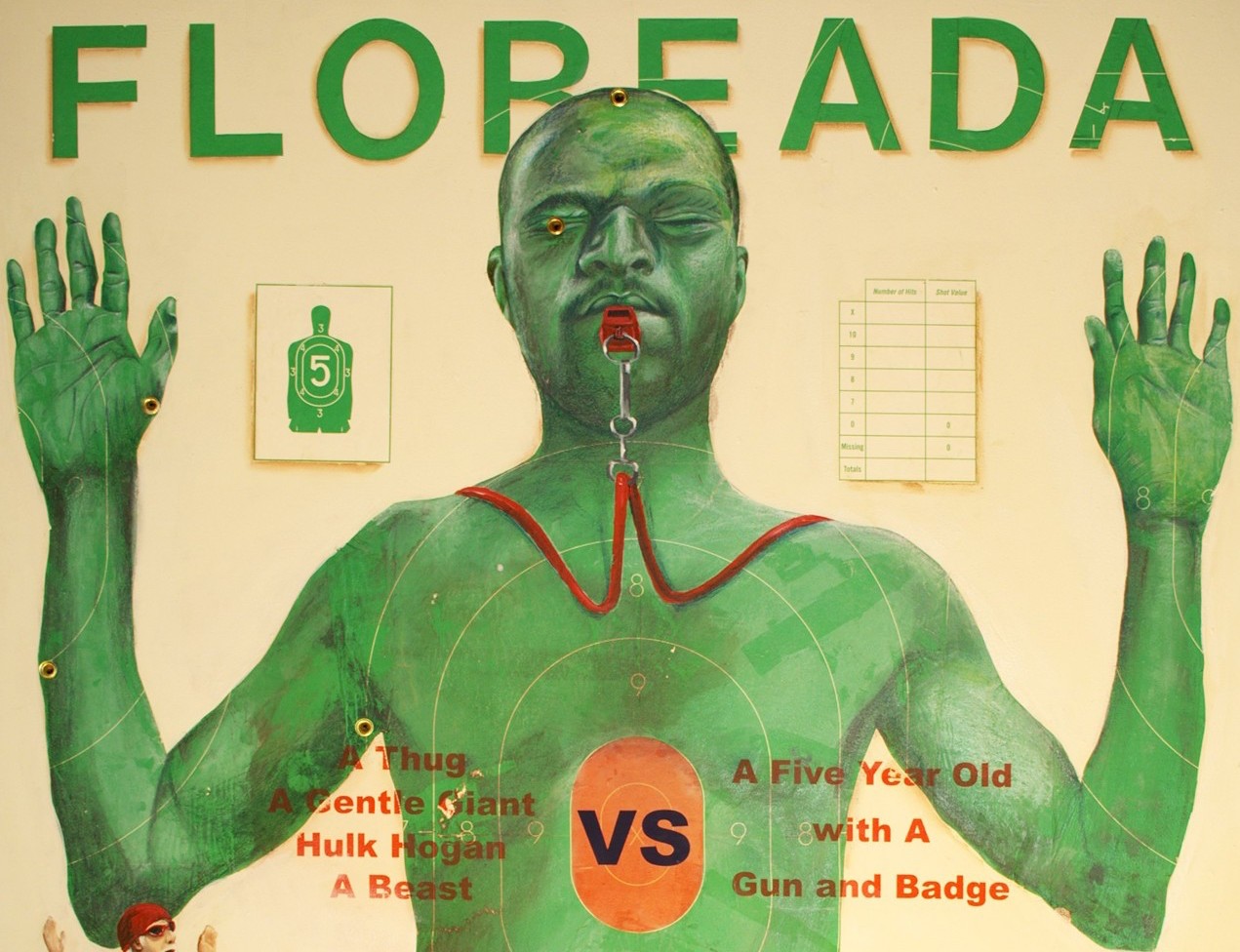

The timeline is the spine of Viral: 25 Years Since Rodney King, currently on view at Betti Ono through October 22. But the flesh is what surrounds it: portraits of victims, photographs of the sites where they were killed, collages depicting the number of bullets shot at them, renderings of their mothers’ faces, and every sort of response to the epidemic of police violence against Black people in America. Altogether, fifty artists — from emerging to nationally acclaimed — contributed to the show.

“I really wanted to drive home the reality that this has never gone away,” said curator Daryl Elaine Stenvoll-Wells of the exhibit’s format. “No matter these waves of public attention that happen, the issue has never gone away and is consistently getting worse.”

Stenvoll-Wells is originally from Los Angeles, but began working in the Bay Area as an arts educator six years ago. In 2013, however, the death of her brother drove her to reassess her life. Although it appears that he died of natural causes, Stenvoll-Wells said he was consistently harassed by police, and his death ignited in her a flame for justice. She quit her job and began teaching herself digital-art techniques and making portraits of police-shooting victims.

Not long after, Stenvoll-Wells founded Art Responders, an online platform for sharing artwork made in response to police brutality. And earlier this year, curators at the Social and Public Art Resource Center in Los Angeles asked Stenvoll-Wells to show some of the portraits she had been making in their gallery. Instead, she tapped her Art Responders network to create VIRAL, which opened at SPARC this past March. After its stint at Betti Ono, Stenvoll-Wells intends for the show to continue to travel at least until April of next year, the official anniversary of the L.A. uprisings.

Despite the show’s title, viewers shouldn’t expect a dissection of the role that virality plays in the current movement for Black lives. In fact, the show’s title almost seems to apply more to its depiction of police violence than videos thereof. As Stenvoll-Wells described the issue: “It’s like a cancer on the American future.” In that sense, each piece of art is like a white blood cell, working together to fight away at the deadly disease.

That’s not to say that the show isn’t technologically minded or forward-thinking. At the end of the timeline, past 2016, there’s a section of the gallery dedicated to Perspective: Chapter 2; Misdemeanor, a virtual-reality experience released earlier this year at the Tribeca Film Festival. The piece, created by filmmaker Rose Troche (The L Word) and VR pioneer Morris May, allows the viewer to experience a violent police interaction through four different perspectives: the young Black boy suspected of shoplifting, the boy’s friend, the interacting police officer, and the officer’s colleague. Each view reveals different details, such as the officer muttering under his breath in stress and the horizontal viewpoint of a boy with his head pressed against the ground.

At this point, the quality of inexpensive virtual reality often isn’t exceptional. But the piece could still easily move any empathetic person to tears.

Sitting across the gallery from a painting of King’s black and blue face, Misdemeanor is two things: In form, a testament to how far we’ve come; and in content, a testament to how little progress we’ve made.

Ultimately, for Stenvoll-Wells, it’s the content that matters most. Of possible ways to take action, she said: “I don’t care what you do, just do something.”