The 2006 Youth UpRising Christmas party featured healthy helpings of fried chicken, greens, and mac and cheese. That was certainly part of the appeal for the several hundred young people in attendance, the majority of whom were low-income and could be considered at risk of falling into lives of drugs or violence. But to their delight, the party also boasted a contingent of ghetto celebrities, including the head of a hip-hop record label founded by the late Mac Dre and the popular rappers E-40 and Mistah F.A.B.

Turf-identified rappers seldom interact directly with fans or involve themselves in community affairs — actions seemingly at odds with their hypermasculine public images. But that’s just what happened on December 22. President J. Diggs of Thizz Entertainment donated shoes, warm coats, T-shirts, and PlayStation IIIs to needy youngsters. He even went so far as to disassociate himself from “thizzing,” street slang for using the drug Ecstasy.

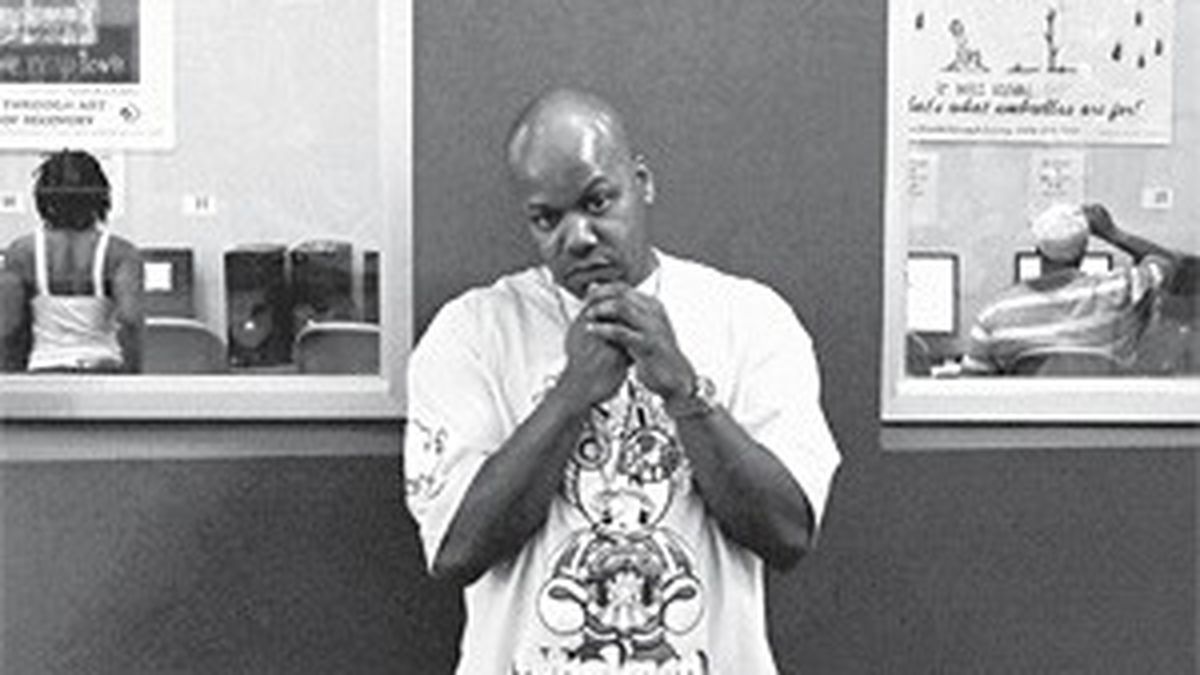

But the afternoon’s biggest surprise came when Todd Shaw — aka Too $hort, the most iconic Oakland rapper of all time — announced that he was moving back to “tha town” and joining the two-year-old East Oakland community center as a career counselor. $hort’s remarks were met with cheers, and attracted favorable notice from San Francisco Chronicle columnist Chip Johnson four days later — yet also drew pointed criticism from one of Youth UpRising’s most outspoken opponents.

On January 20, Charles Pine of the anticrime group Oakland Residents for Peaceful Neighborhoods posted criticism on its Web site, and made his views known to members of the city council. Under the headline “Listen, Oakland Officials, to National Debate Over Rap,” he complained that Youth UpRising was receiving city funds while working with rap artists who irresponsibly “promote sideshow culture” — an allusion to the outlawed ghetto gatherings known as sideshows. Pine called the participation of Youth UpRising dance groups in rap videos, and the nonprofit’s teaching of music- and video-production skills “a modernized form of poverty pimping” unlikely to produce much in the way of long-term employment. Finally, he called Too $hort an unacceptable role model due to his frequent use of the word “bitch” and his promotional relationship with Remy Martin cognac.

It certainly wasn’t the first time Shaw’s persona turned out to be both blessing and curse. Too $hort had brought him fame, fortune, and a loyal, multigenerational fan base. It also has defined him rather narrowly. Despite Shaw’s significant musical accomplishments, many can’t get past his signature phrase — biiiiaaaatch! — and the way he draws out its syllables in a way that seems to boost its offensiveness.

Still, the rapper has few regrets. Like Frank Sinatra, he’s a legend who has done things his way. Now 41 and graying, he has had one of the longest and most prolific careers in the hip-hop game. In the early ’80s, when rap first spread from New York to California, Shaw immediately gravitated toward the new sound, performing at house parties and adopting his now-ubiquitous alter ego.

As $ir Too $hort, he began making personalized tapes for pimps and dope dealers in the hardcore ghettos of East Oakland, later selling homemade cassettes on the 43 bus line or “out the trunk” of his car. As word spread, a local label put out three solo $hort albums, Don’t Stop Rappin’, Players, and Raw, Uncut, and X-Rated, which quickly became de facto soundtracks for the Oakland streets. $hort’s topics ranged from on-the-spot reportage about the then-burgeoning crack epidemic in “Girl (That’s Your Life)” to puerile yet humorous discourses on fellatio in “Blowjob Betty.” A falling-out with the label led him to launch his own Dangerous Music label, which released the now-classic Born to Mack in 1987.

Though now clichéd, Born to Mack‘s fables seemed fresh at the time. While bearing stylistic influence from Run-DMC, LL Cool J, and Eric B. & Rakim, the album took hip-hop in an entirely new direction. Scandalously risqué and unabashedly ghetto, it drew its inspiration not from the usual Bronx tales but California lifestyles. Its best-known song, “Freaky Tales,” established a template for what would become the “West Coast” rap sound: slow and funky, with an emphasis on heavy bass.

But more notoriously, $hort strived to make pimping cool, portraying himself as an inner-city cartoon character whose dirty mouth and clever rhymes made him irresistible to women. This was the Record Your Parents Didn’t Want You to Hear, though by today’s standards, and partly due to its influence, its lyrics no longer shock:

I met this girl, her name was Joan

She loved the way I rocked upon the microphone

When I met Joan, I took her home

She was just like a doggy all up on my bone

I met another girl, her name was Ann

All she wanted was to freak with a man

When I met Ann, I shook her hand

We ended up freaking by a garbage can

The next young freak I met was Red

I took her to the house and she gave me head

She liked to freak is all she said

We jumped in the sheets and we broke my bed…

Even more notorious was “Dope Fiend Beat,” an underground anthem which made biiiiaaaatch! synonymous with Oakland. Born to Mack sold a reported fifty thousand copies in the Bay Area alone, strictly on word of mouth. When New York label Jive released the album nationally, it sold two hundred thousand more without the benefit of video or radio play.

His next album, 1988’s Life Is … Too $hort, established the artist as one of hip-hop’s first regional stars. The album was divided into “clean” and “dirty” sides, corresponding to the Todd Shaw/Too $hort dichotomy. Without promotion, Life Is sold three hundred thousand copies in three months. After MTV picked it up, sales eventually broke two million.

$hort went on to release a string of albums that went gold or platinum, among them 1992’s $horty the Pimp, 1994’s Get In Where You Fit In, and 1995’s Gettin’ It.

In the mid-’90s, Shaw moved to Atlanta, where he flirted with retirement but instead hooked up with a then-unknown rapper named Lil’ Jon for “Couldn’t Be a Better Player,” one of the Southern “crunk” movement’s first anthems. In 2003, the two teamed up on “Burn Rubber,” one of the earliest representations of the Bay Area’s ascendant “hyphy” sound.

Too $hort will go down in history as a pioneer of independent rap, the uncle of crunk, and the grandfather of hyphy. According to Wikipedia, only he and two other rappers, LL Cool J and Ice Cube, have notched six consecutive platinum albums (more than a million sold). But even more remarkable is his continued relevance — there aren’t too many 41-year-old rappers still making hits.

John “Casual” Owens, a Youth UpRising employee and member of the Hieroglyphics rap crew who grew up listening to Too $hort, says that even today the rapper has “the most star power out of any entertainer who comes from Oakland.”

It would be myopic to suggest that the rapper’s long career has been one-dimensional. Hardcore listeners may have been entertained by his salacious tales, yet he has subtly slipped positive messages and life lessons in between the odes to getting head in a Cadillac. Indeed, his positive side is what separates him from now-obscure, similarly ribald peers such as 2 Live Crew and Akinyele. In interviews, $hort frequently points out that his top-selling single was 1990’s “The Ghetto” — a poignant plea for self-esteem in the inner city — and he’s championed the themes of self-determination, entrepreneurship, and independence again and again.

“I never wanted to be a drug dealer; I never wanted to be a pimp,” Shaw says today. “I really wanted to make music and tell the story of Oakland, California, which is a city that just fascinates me to this day.”

Despite this, $hort will always be known as the first “pimp” rapper. But Owens, for one, believes even a pimp should be allowed to evolve. “That’s definitely how he came up and how he made his money,” he acknowledges. “To say that things from the past or bad things he may have said about a girl should prevent him from helping the community, that’s just ignorant.”

Still, there’s more than a little irony in $horty the Pimp becoming a mentor to highly impressionable youth.

Almost four months after the Christmas party, Todd Shaw is discussing Too $hort with some kids at Youth UpRising. He’s talking about their plan to use a line from his hit single “Blow the Whistle” in a video they are producing. The verse has swearing in it (What’s my favorite word?/Bitch!/Why they gotta say it like $hort?), and using cuss words is strictly prohibited at Youth UpRising. “You know you’re gonna have to edit that, right?” he asks. Reluctantly, the kids nod.

Some might find it hypocritical for the author of “The Bitch Sucks Dick” and “Shake That Monkey” to counsel others about their use of swear words. Still, it’s a test of the rapper’s humility to let himself be used as a prop in a production whose budget is so low that the video camera is a cell phone.

In the script, the kids are watching Too $hort videos when the real $hort walks in carrying a plate of chocolate chip cookies. They rehearse the scene several times; each time, the number of cookies gets smaller and smaller. As the kids struggle to get it right, the rapper dutifully and patiently repeats the process until the kids have eaten all but two of the cookies. His behavior suggests Shaw has mellowed considerably with age, although his recent recordings certainly haven’t shied away from the explicit lyrics that made him an inner-city sensation. “I’ll never curse in this building,” he says, seemingly more to himself than for the benefit of a reporter within earshot.

Shaw first visited the center last September after learning that his friend Owens was working there. When another friend got a job there, he kept dropping by. “They said, ‘Hey, the kids really like you,'” Shaw recalls. “‘It seems to be a mutual admiration thing going on — would you like to get involved?'”

As a self-made millionaire, Shaw can afford to do it for the love. “My main thing is that I have no financial benefit from this scenario at all, and I have no intentions of financially benefiting,” he says. To him, what’s going on at Youth UpRising is about lives being saved: “They’re off the streets and they’re learning, you know what I’m saying?”

Rappers are known for big egos, and $hort is no exception. But as a youth adviser, Shaw comes off as surprisingly ego-free. He doesn’t dress extravagantly, showing up most days in a simple T-shirt with a bejeweled “2” pendant, his only concession to bling. Nor does he cop an attitude with the kids, and he goes out of his way to be accessible, visiting different classes, popping his head into production studios, hanging out in the lobby, and letting the kids flock to him.

Which they do. They’re not exactly overwhelmed to be in his company, but are intrigued by his presence. “Why do they call you Too $hort?” one young woman asks flirtatiously. “Because I was five-foot-two when I graduated high school,” he replies (he’s now about five-seven). “What does the two stand for?” another asks of his medallion. “I was born on April second,” he says. Despite being a guy who has made his living using misogynistic epithets, he is the picture of politeness and respect when addressing these adoring girls.

What do the kids have to say about him? “He’s like anyone else,” says thirteen-year-old Cooper “Coop” McGill, one of a handful of white kids at the center. “Except for he’s a legend who’s sold, like, ten million records.” McGill, who has been coming to Youth UpRising for four months, admits he was a bit starstruck at first, but he’s gotten used to the rapper’s presence. Unlike most adults, McGill says, when he first met $hort, “he was really interested in what you said.”

Like many of the kids here, McGill says he wants to get into the music business. He and $hort frequently discuss it whenever Shaw comes through. “He’s real accessible,” he notes, adding, “It’s a big thing for YU to have somebody come in and actually show love. That means we’re doing something right.”

LaJazz Harper, seventeen, who’s been coming to Youth Uprising since it opened, reports that $hort helped her with a school paper by giving her an interview. “Every time he comes up here, he’s a nice guy,” she says. “Beyond all the negativity people try to put on him because of his music, he’s genuine at heart. And he’s all for the kids. He stops and talks to us — he’s not like some rap artists that might come through that don’t have time.”

Sixteen-year-old Clayton Tarvins proudly notes that he and his dance crew the Architeks were featured in $hort’s “Blow the Whistle” video, which opened up a new career path for them. “Being in the video, we got some money and stuff. He does it to help the youth, ’cause when he was a youth they couldn’t do stuff like that,” Tarvins speculates.

Nonetheless, Tarvins adds, “Sometimes my mama don’t be letting me listen to him all the time” due to the lyrics, which she feels degrade women. Even so, he says $hort is a role model simply because he’s an East Oakland success. “When he started rapping, nobody thought he could make it, and he made it,” he says. Most importantly, the young man says, $hort’s presence helps entice young people to Youth UpRising: “If they know that Too $hort be coming here, they probably gonna keep coming back. And they’re gonna quit being on the streets, selling dope, and fighting.”

Although Shaw says he’s still trying to find a routine in his work at Youth UpRising, he seems to be following his alter ego’s advice to get in where you fit in. So far, he doesn’t keep regular hours, and his still-evolving role has been as a counselor and adviser-at-large. Recently, he’s been working with Owens to help the center set up a limited liability corporation to function as an in-house record label staffed and operated by Youth UpRising members. His ideas include developing an Internet presence, in addition to pressing 2,500 to 5,000 CDs for retail. There also are plans for a spoken-word album and a documentary.

Shaw notes that music courses he took in school inspired his own career aspirations. He then points out that Castlemont, the high school next door, currently has no music program. “My man over there,” the rapper says, pointing to a nearby kid, “he can sing, he can play the keyboards, he plays drums, he can make the beats. He’s probably like about fifteen. He’s in the right place. … He can’t come to music classes at school, so if he couldn’t come here … “

He doesn’t have to finish the sentence.

Olis Simmons, Youth UpRising’s executive director, says she’s unimpressed by Too $hort’s rep. “I don’t think I’ve ever met $hort,” she recently told Ozone magazine. “I’ve always talked to Todd.” Still, there is no denying that $hort’s name recognition and street credibility have helped her get Youth UpRising members off the streets and into the studio. What impresses her, she says, is Shaw’s “level of humility … he so doesn’t buy into the hype of Too $hort.”

Neither does she. She’s no groupie, she says, and isn’t looking for free concert tickets or a ride in Shaw’s Mercedes. She just wants her kids to survive and thrive despite the challenges they face. Before someone joins the Youth UpRising team, she says she asks herself, “Is this a person who’s gonna be appropriate around young people? It really is a question of integrity.”

Integrity is a word Simmons’ uses a lot. She stresses the importance of “staying in integrity with youth culture” and relating to young people “where they are.” That’s where Shaw fits in. If you can both relate to young people and “meet their needs for education, safety, and health, you can create a win-win situation,” she says.

A 46-year-old New York transplant who moved to Oakland in 1984, Simmons retains plenty of East Coast no-bullshit attitude. She prides herself on walking the walk. When Hurricane Katrina hit, she volunteered for a ten-day stint on the disaster-relief frontlines, helping the Red Cross dispense relief money to survivors in Biloxi, Mississippi. While that may seem atypical for an executive-level bureaucrat who oversees a $7 million budget, Simmons says she volunteered because “I was willing to show young people we are all connected.”

Youth UpRising is seen by many as one of the few points of light emanating from Deep East Oakland these days, a community that bore the brunt of the city’s 148 murders in 2006. It is designed to be a safe place where youth can interact with peers and get counseling, health services, and job training. Simmons says she was responsible for the bulk of the planning for Youth UpRising, which was first proposed in 1992 and opened in 2005. The teen center’s multifaceted approach includes everything from job training at a member-run cafe to a stay-in-school teen pregnancy program. Simmons helped secure the center’s funding and hired its staff, and in many ways it reflects her personality.

The 25,000-square-foot building, bought for $2 million and renovated with an additional $6 million, looks like a place young people would want to be. Positive messages resonate from almost every corner, and pictures of success stories are posted online and on the walls, along with testimonials from members (“After I came to YU I stopped fighting hella much”). All of it is designed to give its young clients some hope.

Tapping into hip-hop as a way to facilitate youth mentorship and violence prevention is still a fairly new concept, yet there are some indications that doing so can reach young people where more traditional approaches have failed. Chris Wiltsee, executive director of Oakland’s Youth Movement Records — a youth-run record label operated as a community-oriented nonprofit — says his program boasts a graduation rate above 90 percent.

Hip-hop helps Youth UpRising reach kids. “First and foremost, when they’re in here, they’re not out there,” says Geoffrey “Unknown” Murihia, the center’s media arts coordinator. Studio time is free, but members have to be enrolled in production and engineering classes — they can’t just come in, bust a rhyme, and leave: “Now they’re not just looking at a career in rap; now they’re also looking at a career in production.” In addition to pursuing music industry internships, Murihia is setting up accreditation protocols, so that Youth UpRising classes could one day lead to community college degrees.

Simmons defends Youth UpRising’s growing connection to the hip-hop community as a factor in helping steer young people into the center’s other programs. Asked about concerns over $hort’s participation, she replies, “I’m more concerned about homicides than underage drinking.” She also finds great irony in the most prolific pimp rapper of all time helping to build interest in a center that takes a stand against teen prostitution.

She says Shaw is an invaluable resource for both business and talent development and that he, E-40, and Mistah F.A.B. have helped her programs immensely. As an example, she points to the center’s soon-to-be-released spoken-word CD, which addresses “violence and the devastating impact” it has on young people’s lives. Shaw personally recorded an intro for the disc. “There’s no denying the album is made stronger by his contribution,” she says.

On a recent afternoon at the center, a dry-erase board at the reception desk lists a wide range of after-school classes and activities, including “turf dancing,” video production, and music production. But the last event of the day is the soberly titled “Violence Prevention Workshop.” The inference is clear: Youth UpRising’s two thousand members, ranging in age from 13 to 24, may come here to have fun, develop their talent, and find their community, but if they stick around long enough they’ll learn some life-enhancing skills.

For that reason, Simmons believes Charles Pine is way off-base in his attacks. If she’s correct, educators may one day tout the Youth UpRising model. But if she’s wrong, might her center’s association with hip-hop artists actually propagate what Pine calls a “culture of disrespect that has turned Oakland into a living hell for most of its flatland residents”?

Like many Oaklanders, Charles Pine is fed up with crime. His vision of Oakland revolves around one recurring theme: Better living through improved law enforcement. Proclaiming Oakland “the most underpoliced major city in the US,” he has continually expressed his unhappiness with a Measure Y-mandated increase in the amount of officers from 724 to 802 over the next two years, believing that the “citywide solution is at least 1,100 police.”

An attorney by trade who is perhaps better known as a political gadfly, Pine doesn’t hesitate to hurl insults at Oakland city officials from cyberspace. The Oakland Residents for Peaceful Neighborhoods Web site accuses Jane Brunner of existing “in an alternate universe,” calls Jean Quan a “one-eyed councilmember,” and wonders, “Do we have a city hall or an insane asylum?”

But some of Pine’s most fervent attacks are reserved for Measure Y, hyphy rap, and sideshow culture, which to him seem to form an unholy trio whose nexus is Youth UpRising. Pine declined several requests to be interviewed for this story, but he wrote the following on his site: “You might not care for hyphy, but you are paying for it. Next time you are about to scream in pain and helplessness as a series of ‘boom cars’ passes your house, thank the Oakland City Council for selling you Measure Y and giving a chunk of its money to Youth UpRising.”

Pine hasn’t ever visited the center, although he’s easily its biggest detractor. After Simmons extended an invitation to tour the facilities, Pine posted this in response: “Let’s be clear about the problem: A music video celebrity, E-40, makes a video glorifying sideshows.” Noting that center-trained dancers appeared in the video, Pine says, “We raised one question: Since Youth UpRising is financed in part by Measure Y violence prevention money, is this an appropriate activity?”

City officials, by and large, have nothing but praise for Youth UpRising. “If every one of my teen centers and rec centers was like they are, we’d have a lot more kids off the streets,” Councilwoman Quan says. She sees no problem with Youth UpRising’s affiliation with rappers, although she’s aware that sideshows are a concern for many families.

Captain David A. Kozicki of the Oakland Police Department lauds Youth UpRising for providing alternatives to crime while emphasizing the need for social responsibility. He says the center has stepped in to provide a supportive, nurturing environment that’s often missing at kids’ homes. He also notes that it’s one of the few social service programs with a genuine interest in working with the police. The center catered an open house at the OPD’s East Oakland substation, and Youth UpRising kids have also volunteered at a drunk-driving checkpoint. Additionally, Kozicki chaperoned an excursion to a Raiders game for one hundred at-risk kids. “Some of these kids are from East Oakland and have never been to the Coliseum,” he says.

Kozicki says Pine is “pretty much on-point” with his laments that the OPD is understaffed. However, he believes that Pine’s complaints have been largely unfair, and says Pine’s group falls short when it comes to identifying viable solutions to Oakland’s urban ailments. “It’s easy to say we need 1,000 police officers and no new libraries,” but the reality is that “we are not going to arrest our way out of these problems that are happening in our city. There’s not enough prisons, there’s not enough courts. We can’t put ’em all in jails.”

The 26-year OPD veteran is responsible for sideshow enforcement, and admits to some concerns about rappers such as Too $hort glorifying sideshows in their music. Still, he believes their involvement with Youth UpRising is positive. “If Olis can reach out to rappers, that’s a good thing,” he says. “Olis’ program is about teaching kids how to have responsible fun. If that means dancing, or hyphy without Ecstasy, that’s okay.”

Youth UpRising’s latest attempt at brokering peace in Oakland involves unlikely bedfellows: $hort, Mistah F.A.B., and the entire OPD Senior Command staff, who have joined forces to address public safety concerns. That’s a marked change from seventeen years ago when, in “The Ghetto,” $hort complained: Housing Authority and the OPD/all these guns just to handle me. Then, as now, Oakland faced a homicide crisis. Yet instead of complaining about police misconduct, $hort has followed his own advice — “I better help myself” — and gotten proactive about a situation that has only worsened over time. Using the rapper’s ability to reach the youth, the group has produced a series of radio public-service announcements. Upcoming events include a fashion show and block party at DeFremery Park in West Oakland on September 15, where Too $hort will perform — naturally — “The Ghetto.”

Yet even for those who approve of Youth UpRising’s involvement with hip-hop artists, at least one of Pine’s complaints seems valid. Last January, a Remy Martin-sponsored promotional appearance by Too $hort at the Uptown Market in North Oakland was shut down by police after it attracted a large, unruly crowd. Too $hort was autographing branded Remy Martin posters of himself for neighborhood kids, some of whom were under age. The liquor store was cited for promoting underage drinking.

Following this incident, Pine wasted no time taking the offensive. “Apparently, for Too $hort, a call back to the streets of Oakland means disturbing a neighborhood with a huge stereo trucked into a liquor market in order to promote cognac to youth — then recommending that youth pursue the same career,” he wrote on his Web site.

Pine has since questioned the Oakland City Council’s idea to build several more youth centers along the lines of Youth UpRising. He downplayed a Department of Human Services report calling it “one of the best examples of a successful youth center,” and once again criticized it “for promoting sideshow culture and gutter rappers.”

Shaw is obviously keen to recast his legacy along more positive lines. On a recent weekday afternoon, he stands in the middle of Youth UpRising’s media production room, which is teeming with activity. “You can’t tell me it’s a bad thing for me to get involved,” he says.

A two-tiered row of computers in the center of the room has become a beat-making laboratory, and a cascading series of piano notes emanates from one of the recording studios. Down the hall, in a small mirrored studio, dancers practice their routines. The whole thing resembles an inner-city version of the TV show Fame, except the kids are younger and far less privileged.

None of these things were available for young people in East Oakland a quarter-century ago, when Shaw first became $ir Too $hort. But more than just studios and equipment, he emphasizes, the center provides its members things they can’t find on a street corner: guidance and support. “The older kids in the building know for a fact what’s gonna happen if you take the wrong turn,” he says. “I could pull out five guys in the building right now and have them tell some stories about homeboys who did it wrong. We got, like, a list of dead homies. We got a list of homeboys who ain’t coming home no time soon to enjoy their lives. When they come home, it’s like, they coming home as senior citizens.”

Of his own youth, Shaw says that when he first became a successful rapper, he was occasionally approached by drug dealers offering him a cut of their profits if he’d front them a stake. “I feel like I just barely made it around the obstacles,” he says. “Somebody would always pull my coat and say, ‘You idiot, you’re thinking about doing that?’ … I always had homeboys that came to me and was, like, ‘Man, you got a good thing.'” He says his motivation for getting involved is simple: “I feel like I need to be that homeboy.”

Shaw now says his affiliation with Remy Martin, which reportedly paid him $50,000 to appear in a series of promotional events at liquor stores throughout Oakland, ended before he officially joined Youth UpRising’s staff. He admits that the relationship constituted “a very clear and evident” conflict of interest. “To promote alcohol and to work with kids at a youth center; I felt like one had to give,” he says. “So the Remy gave.”

Noting that he doesn’t get many endorsement opportunities, he says the choice wasn’t difficult: “I prefer to be on this end of it.” Remy Martin’s US Web site now features SF-based rapper San Quinn as its “Oakland” representative.

After observing Shaw at Youth UpRising, it’s fair to say he’s learning as much from the kids as they are from him. It’s also apparent that his involvement has had an effect on him. After 25 years and 16 albums as Too $hort, this side gig has allowed Todd Shaw to set aside his alter ego and just be himself. It’s fitting that the spirit of community transformation that lives and breathes at the center has changed him as well. After all, redemption is a two-way street. <p