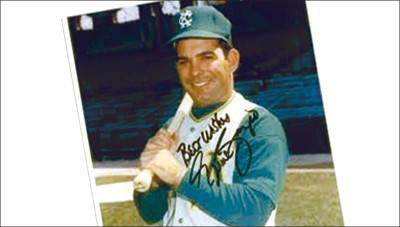

If Ernie Fazio were Major League Baseball’s most promising young prospect today, he’d be set. He would have a multimillion-dollar contract, and if he stayed in the big leagues for a mere 43 game days, he’d be guaranteed an annual pension check after retirement. Unfortunately, the San Leandro native was the game’s top prospect almost fifty years ago, when Hall of Famers like Willie Mays and Mickey Mantle took home about $100,000 a year.

In 1962, while leading the Santa Clara Broncos to the final game of the College World Series, Fazio had more home runs than any other NCAA college baseball player. Three days after that game, Fazio was on a plane to Houston to make his debut in “The Show” as a member of the expansion Houston Colt .45s. But Fazio struggled in the majors and after just three seasons — including a 1966 stint with the Kansas City A’s before the team moved to Oakland — he was out of baseball, one year short of the time required to be vested in the league’s pension program.

Although Fazio, now 69, has earned a decent living since then, working as a manager in the refuse business, he hasn’t made enough money to retire. “I have to keep working, I don’t have an out yet,” the Alamo resident said. “If something happens to me, my wife and daughter won’t get anything.”

In April, it was announced that Fazio and 865 other former ballplayers who never qualified for pension benefits would finally get something — an award of up to $10,000 a year for two years from Major League Baseball and the Major League Baseball Players Association. Fazio and company are known in the baseball world as the “pre-1980, non-vested players.” They’re the grinders who weren’t in the majors long enough to be vested in the league’s pension program and who also played before the vesting requirement was reduced in 1980, from four years to 43 game days. In short, they’re the guys who slipped through the cracks, who came within reach of what is considered the most generous pension program in America, but wound up empty-handed.

Fazio and others hope this award isn’t the end of the road. They’ve been fighting for some sort of pension compensation for more than a decade; many of them have already passed on, while others are struggling in their twilight years with ailing bodies. Ultimately, the dream is to be grandfathered into the league’s pension program and their last chance might hinge on whether the players association is willing to fight for them in December’s collective bargaining negotiations.

While Fazio said he’s happy to finally be getting something from baseball, others feel short-changed. “They’re basically offering us a pittance,” said former Oakland A’s utility man Jimmy Driscoll, who played less than a year in the majors. “Who cares? It’s chump change.”

Driscoll’s time in the big leagues may have been a quick “cup of coffee” as they say, but he argues that he was part of a generation of players who helped build the game into the $7 billion entity it is today. He rode buses, played through injuries, and paid his union dues; when the players went on strike in 1972 (the first players’ strike in the history of professional sports), he gave up his paycheck just like everyone else. “We went on strike with the hopes of making the union stronger,” Driscoll said. “If we didn’t do that, they wouldn’t be making the kind of money they’re making today.”

The modern player has it good, no one can argue with that. Today’s minimum league salary is $414,000; the average salary is $3.3 million. And, of course, only 43 days in a big-league uniform gets you a pension check after retirement. Players who last more than ten years receive annual pension checks averaging roughly $180,000 once they reach the age of 62.

While this award grants the non-vested player up to $10,000 for two years, the actual amount is contingent on time served, so most of the eligible players likely won’t get more than a few thousand bucks. And some of them could really use more. Take Jimmy Hutto. He played nine years of Triple A ball, but only made it up to the big leagues for parts of the 1970 season with the Philadelphia Phillies and another few games with the Baltimore Orioles in 1975. The most he ever made in a season was $17,000.

Since he hung up his cleats, Hutto’s made a living by cleaning carpets and fixing houses. But a stroke in 1996 delivered a knockout blow to his finances. Without health insurance, he said the five-day hospital bill cost $9,000. Two years later, he needed knee replacement surgery that he claims is baseball related, and this time the price tag was $22,000. “This award won’t do much of anything for me,” Hutto said.

Others feel robbed by the cutthroat culture of baseball in those days. Some players weren’t able to accumulate four years in the majors because they got hurt and were forced to play through the pain until they were completely broken. In 1967, Bill Denehy was a promising young flamethrower for the New York Mets, but in May of that year he suffered a small tear in his rotator cuff. “It was frowned upon to go on the disabled list. They would say, ‘If you can’t pitch, why should the organization pay you?'” Denehy said.

He struggled but continued to throw despite the pain. In one 26-month span he received 57 cortisone shots. “I took anything that I needed to take to pitch,” Denehy said. “The alternative was selling shoes.” In general, the Mayo Clinic recommends no more than four cortisone shots in a year.

Nowadays, a young pitcher with Denehy’s talent is treated like a major investment. The first sign of arm trouble and he’d be shut down completely, would undergo surgery, and would be given all the time needed to heal.

But none of these guys — Fazio, Driscoll, or Denehy — ever expected to receive any compensation, until 1997, when baseball decided to remedy a past social injustice by creating a benefits package for a group of former Negro League players who were shut out of the game by racial discrimination. Later that year, the league set up another package for a group of players who retired before the pension plan was established in 1947. Suddenly, these non-vested players were the only class of former big leaguers without a piece of the pie.

That’s when things got messy. In 2003, Fazio was a lead plaintiff in a lawsuit that accused Major League Baseball of racial discrimination against the non-vested players by not extending to them the pension-compensation package awarded to the Negro Leaguers. But the Ninth US Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against them in 2006, saying they had failed to establish a prima facie case of discrimination. The end result was a lot of bad blood between the players and the league. “Looking back on it, it was probably a tactical error because everyone’s ego got bruised,” said David Clyde, a non-vested player who’s lobbied for compensation as a member of a special Major League Baseball Alumni Association pension committee. “It took a long time to overcome that, but I don’t know that there was any other avenue at that point.”

But the league says it’s all water under the bridge now. In December, they’ll sit down with the players association and talk about extending the award beyond two years. “This is a topic that will be discussed in the negotiations,” said Rob Manfred, baseball’s senior vice president of Labor Relations and Human Resources. These former players, however, still hope to be grandfathered in, an outcome that seems unlikely at this point.

Douglas J. Gladstone, whose 2010 book, A Bitter Cup of Coffee: How MLB and the Players Association Threw 874 Retirees a Curve, chronicles the plight of the non-vested player, thinks the players association should unilaterally fund a pension program for these guys. “Why doesn’t the union care?” he said. “Today’s player needs a healthier respect for those who came before him.”

Gladstone estimates that it would cost somewhere between $3 and $7 million to grandfather these former players into the program, a drop in the bucket compared with the cash that gets tossed around every year in free agency. But when asked about the plausibility of funding such a program, Steve Rogers, who handles pension issues for the players association, declined to comment. “That’s not in the purview of what we’re going to talk about,” he said.

By the time things gets sorted out, Fazio may have no more than a few extra thousand dollars to show for his time in the majors. But whatever he gets, the memories of playing in The Show and brushing shoulders with so many legends will prevail. “Baseball has been my life,” he said. “I hit my first major league home run off of [Hall of Famer] Warren Spahn. Nobody can take that from me.”