Mark Baum was born in 1903 in what is now Poland, but was at the time part of the Austro-Hungarian empire. At the age of sixteen, in the midst of World War I, he attempted to immigrate to Denmark. He didn’t have the proper paperwork, but as he stood in line at the border he noticed a door left ajar — an opening to the other side. So, he sprinted through it, and the border patrol never caught up to him.

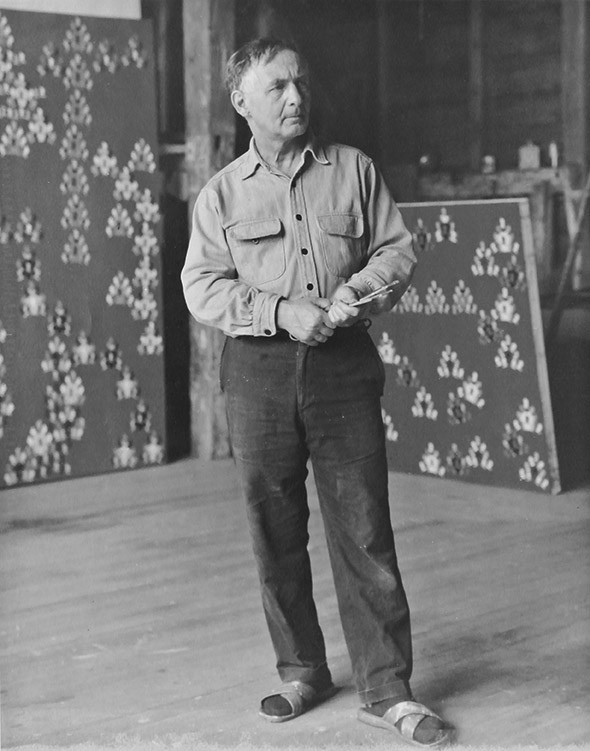

That experience seemed to stick with Baum for the rest of his life, underlying his eventual path to America and ultimately guiding his prolific artistic output later in life. In a solitary barn in Maine, the painter would eventually develop an obsession with ascendancy, producing paintings that appear to allude to spiritual enlightenment and attempting to lead viewers through mental openings into a mystical channel. An in-depth retrospective of Baum’s work that tracks the enthralling evolution of his practice is now on view at Krowswork Gallery (480 23rd St., Oakland) in the show Mark Baum: Elements of the Spirit.

Shortly after Baum made it into Denmark, he immigrated to America. Once in New York City, the alienated Jewish transplant made a name for himself painting urban and pastoral landscapes. He managed to succeed in selling art, but in the mid Forties, as World War II was coming to an end and abstract expressionism was taking over the New York art scene, he grew disenchanted with it all. Not long after his work was featured in Life Magazine, Baum moved to Maine. There, he began developing a nonfigurative visual language by which to artistically probe into philosophical musings, developing a pseudo-religious art practice that he would continue until his death at the age of 94 in 1997.

Throughout the Fifties, Baum’s compositions grew increasingly spare and abstract. Cityscapes turned to floating staircases leading allegorically up to a glowing door or lush meadow. But in the early Sixties, he made the most important pivot of his career. He whittled down his visual vocabulary to a singular “element” — a shape that resembles the silhouette of a sail boat, which for him epitomized the upward movement symbolized by staircases. Assembling the shape into various permutations in a range of remarkably vivid hues, the shape itself became a kind of medium for Baum, and the only one he employed for the rest of his career.

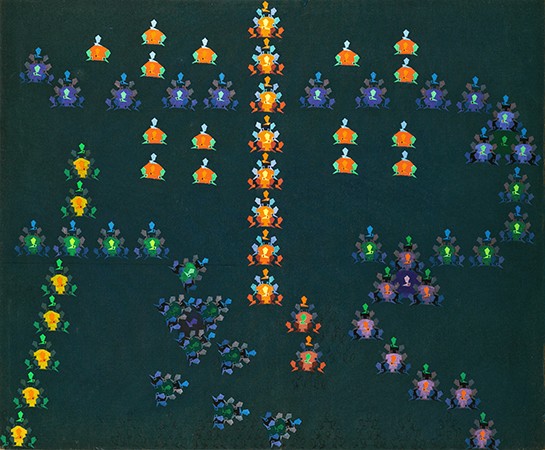

For the 1968 piece “Towards Certainty,” Baum arranged the symbol into triangular formations that crawl their way up the bright green canvas in colors that recall Tibetan mandalas. As Leora Lutz points out in the catalogue for the show, Baum himself likened the symbol to musical notation. The paintings do have a lyrical quality, although the melody they represent remains mysterious.Krowswork curator Jasmine Moorhead sees each of Baum’s paintings as a psychic map — a take colored by her discovery that he was an avid collector of circuit boards. For her, that hobby affirmed his interest in exploring the ways in which energy is channeled, both technologically and spiritually. “What else is his element but a code, and each of his compositions algorithms?” Moorhead writes in the introduction to the catalogue. “Yet for him, the goal was not an app or a game; he was using his element to create spiritual and emotional spaces that would resonate with those who saw them without words, beyond known language, into otherwise invisible realms.”

Moorhead first learned about Baum through his son, Billy, who lives in the Bay Area. Although Baum’s early work was collected by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1983, his late work was rarely shown and his paintings have never been displayed on the West Coast before. Spiritualism was still considered a passé subject to explore through fine art during Baum’s era, Moorhead pointed out. But she feels that now is the perfect time to look back at it, and the Bay Area — with its confluence of conversation around both spirituality and tech — is the ideal place to do that.

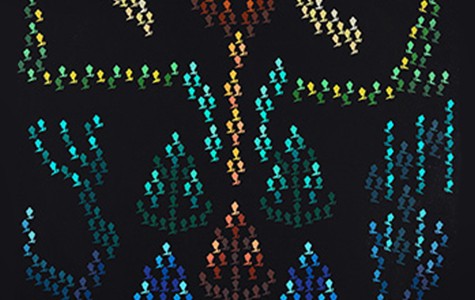

But the most fascinating aspect of the show is how vividly it allows viewers to trace Baum’s psychological evolution without offering any definitive explanation of what, exactly, he was constantly reaching to articulate. By the end, it’s clear that Baum employed his triangular element not merely as a compositional tool, but a visual mantra of sorts.

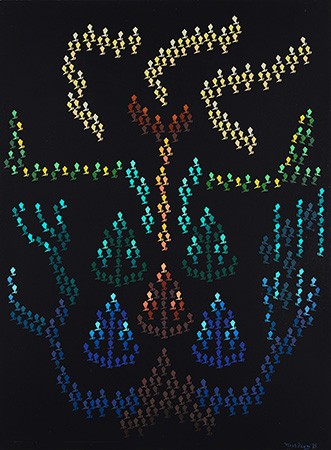

The exhibit includes one of his last paintings. On a black canvas, two rows of his elements interlock each other, repeating to form a zipper-like path that curves around the canvas in a gradient from red to orange. Then, in the upper left corner, it suddenly cuts off. And in an unusually arbitrary arrangement, a cluster of golden shapes float amid the darkness, glowing like little windows into another world.