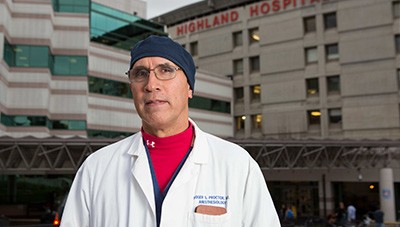

On July 1, Roger Proctor, an anesthesiologist at Highland Hospital in Oakland, saw two very sick patients who he believed were not getting adequate care. Both had severe, life-threatening illnesses and needed surgery, and the hospital had carelessly put them in risky situations. Medical staff had left one patient, who should have been monitored, unattended in a hallway outside the operating room for more than thirty minutes, Proctor said. And doctors had prematurely transferred the other patient out of the intensive care unit for surgery without completing a number of important pre-operative measures, Proctor said.

Proctor, who has been at Highland for more than 25 years, raised concerns about the treatment of these patients to a number of his supervisors. “We have created a system [in which] my patient is a number, not a member of the community,” he wrote in an email that night to hospital officials and his anesthesia colleagues. “This is not good medicine. It is not safe and it is not ethical.”

The following day, William Peruzzi, the hospital’s chief medical officer, told Proctor he would need to take an immediate leave of absence, and a few weeks later, the hospital terminated him, according to official records.

“We all choose to work at Highland, because we’re here to help vulnerable people,” Proctor, a sixty-year-old Piedmont resident, said in a recent interview. “Patient safety cannot be compromised in the interest of anything else.”

Proctor and four other Highland anesthesiologists have since filed a lawsuit against Alameda Health System (AHS) — the county public hospital authority that oversees Highland — alleging that officials retaliated against multiple physicians, including Proctor, for speaking out about unsafe care. The doctors added the retaliation claims to a complaint they had previously filed before Proctor was fired, alleging that the hospital was mistreating the anesthesiologists and ignoring critical patient safety problems. Extensive documents that Proctor provided to the Express show that, for years, these anesthesiologists and other hospital staff members had repeatedly raised concerns about a range of patient safety issues, including broken equipment, rushed procedures, and dangerous staffing problems.

Since July, the hospital has also fired another outspoken anesthesiologist and forced a third to resign, according to the lawsuit filed in Alameda County Superior Court.

The labor dispute between the hospital and its anesthesiologists has shed light on what some current and former doctors and nurses say is the hospital’s increasing tendency to prioritize efficiency and cost-saving efforts over patient safety in a way that is putting some of the most vulnerable trauma patients at risk. “This is a very sick inner-city hospital,” said Francesco Isolani, a former Highland anesthesiologist and one of the petitioners in the lawsuit. “We cannot sacrifice patient safety for expediency.” Isolani alleged in the lawsuit that the hospital forced him to resign over the summer after he defended Proctor and raised his own concerns about unsafe practices.

Highland Hospital is a major regional trauma center that serves more than 2,000 critically injured patients a year and has the county’s busiest emergency department with roughly 80,000 annual visits. The public hospital, located in East Oakland, is the largest campus within the Alameda Health System, which is a major provider for low-income people in the region. The vast majority of AHS patients have government-sponsored health insurance — through Medi-Cal, Medicare, and the county HealthPAC program — or are uninsured.

Highland’s anesthesiology department plays a critical role in hospital surgeries, working with physicians to prepare patients for operations, assessing risks, putting them to sleep, and monitoring them throughout the procedures. Although the hospital’s anesthesiologists generally work exclusively for Highland with full-time schedules, AHS classifies them as independent contractors, which means they have many of the same requirements and responsibilities as AHS employees without certain benefits and protections, the complaint alleges.

The Union of American Physicians and Dentists (UAPD) — which represents some AHS physicians and anesthesiologists at other hospitals — has advocated for the Highland anesthesiologists, but AHS has blocked the union from representing them since they aren’t employees, according to the complaint and union officials.

As independent contractors — which the doctors argue is a misclassification that deprives them of retirement benefits — Proctor and others were vulnerable to mistreatment, said the anesthesiologists’ lawyer, Leiann Laiks. Even though as contractors the anesthesiologists lacked certain protections against unfair terminations, Laiks said it was clear that Proctor and another anesthesiologist, Starla Sills, wrongfully lost their jobs in retaliation for complaining about hospital safety. “They were successful physicians for so long for the hospital, and then all of the sudden at the culmination of many complaints, their employment is terminated,” she said. “The timing is certainly suspect.”

According to the lawsuit, along with extensive records of emails and letters that Proctor provided to me, one of Proctor’s supervisors reported feeling threatened by him after he complained to her in person about patient safety on July 1. The next day, documents show that Peruzzi ordered Proctor to go an administrative leave, and officials subsequently required that he undergo drug testing and a psychiatric test to determine if he was fit for duty.

Proctor passed the drug test, records show. But before the psych test results came back, Peruzzi wrote Proctor a letter, dated July 24, stating that AHS was terminating his contract. The letter did not provide a reason. A week later, the psychiatrist that AHS had hired to evaluate Proctor determined that he was fit for duty.

AHS’ termination also came after more than sixty doctors and nurses signed a letter of support for Proctor urging Peruzzi not to terminate him. “He is an advocate for our patients and their safety is his highest priority,” they wrote. “He refuses to be quiet when our patients are put at risk.”

Three staff members who were nearby when Proctor allegedly made threatening comments to a supervisor on July 1 also wrote letters saying the interaction appeared ordinary and not confrontational. (When I met Proctor and Isolani outside of Highland recently, several nurses and doctors and even a patient embraced them and said the hospital greatly missed them).

Sills, a Highland anesthesiologist since 2000, also repeatedly raised concerns about patient safety to Peruzzi and others. And according to the lawsuit, Peruzzi told Sills in September that AHS would be terminating her employment at the end of 2014, because “he is aware of her complaints about Highland and that she does not ‘share the same vision of the hospital as he does.'” (Sills did not respond to requests for comment.)

Several Highland staff members who are not part of the legal complaint — some who requested anonymity for fear of retaliation — told me that the anesthesiologists’ allegations of unsafe practices are warranted. And the emails Proctor provided also show that other doctors, nurses, and staffers have raised similar concerns. A central complaint relates to alleged failures in the hospital’s pre-operative care procedures, mainly skipping certain important steps before surgery that optimize the patient’s chance of having the best possible outcome.

Increasingly, anesthesiologists at Highland have not been getting opportunities to review patients’ conditions and medical histories before surgery, according to Proctor. “Anesthesiologists need to know about the patients before they are on the operating table,” he said, adding that doctors regularly performed surgeries without conducting certain important tests. And patients, he added, were frequently rushed into the operating room before he had a chance to talk with them.

John Taylor, a longtime trauma nurse at Highland, said he has on occasion seen examples of patients who have arrived at the operating room without getting relevant tests — such as electrocardiogram (EKG), pregnancy, and blood sugar tests. “We get sick, sick people,” he said. “If we do not take the time to look at these people as thoroughly as we can, then we do them a disservice.”

Patients at times are also showing up in the operating room before doctors and anesthesiologists are ready for them, which means vulnerable patients can end up waiting in hallways unmonitored, Taylor added. “It has become commonplace to rush patients down into the room, and as a nurse and a community member, I don’t appreciate that.”

Sills raised similar concerns in July, writing in an email to her superiors that because the operating room director was regularly bringing patients down before surgery and anesthesia staff members were ready, there have been cases in which the room hasn’t been cleaned yet or the previous patient hasn’t even left. Other doctors and nurses have expressed similar concerns, emails show.

Since 2013, Proctor and others have also raised concerns about equipment shortages and malfunctions, including broken anesthesia machines and bronchoscopes, the latter of which are the tubes that doctors use to look inside the lung airways and windpipes of patients. Sometimes the digital screens on the anesthesia machines have malfunctioned, essentially going blank, Proctor said. “It’s like flying an airplane and you can’t see out the window,” he said in an interview. The doctors have also repeatedly complained about medication shortages, the lawsuit states.

The suit further notes that the anesthesiologists had also raised concerns about unsafe working hours that had the potential to negatively impact care, with some of them working eighty to ninety hours a week — a situation that was difficult to remedy given their classification as independent contractors.

The doctors filed the lawsuit after their internal complaints — about their employment status and about patient safety matters — went nowhere, according to the suit. The anesthesiologists are seeking damages for lost retirement benefits (since they were excluded from the county’s retirement program as independent contractors) and other economic damages tied to the alleged misclassification and other accusations in the suit.

A spokesperson for Highland Hospital declined to comment on the pending litigation and declined to answer broader questions about patient safety and staffing.

The loss of three of the hospital’s long-time anesthesiologists is also a blow for patient care, given their extensive experience in treating trauma patients, said Taylor, the nurse. “I would trust them with my life. … I have never worked with a better group of anesthesiologists.”