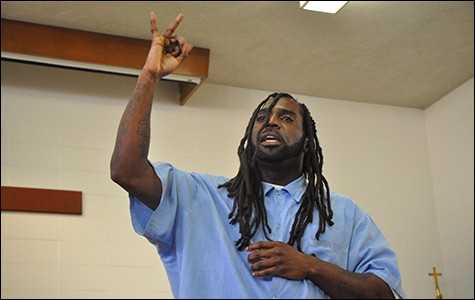

Until recently, Andress Yancy hadn’t given much thought to the works of Shakespeare, and he certainly never thought their themes related to his life. “I thought this was a nerd thing,” said Yancy. But now, after studying works like Hamlet and The Merchant of Venice, Yancy said he has realized just how relatable Shakespeare’s words are. And he learned this as an inmate within the walls of San Quentin State Prison. “Who’s the biggest nerd now?” he said.

Yancy is a participant in San Quentin’s Shakespeare program, which is run by the Marin Shakespeare Company. In addition to staging full-length Shakespeare plays for inmates inside the prison, as well as for select members of the public (typically San Quentin volunteers or friends of the organizers), the program also puts on parallel plays of original work inspired by the Shakespeare productions. Last Friday, the group showcased its latest effort, Parallel Play: Stories from San Quentin Inspired by The Merchant of Venice. The event represented more than just the culmination of long hours spent writing and perfecting the pieces with volunteers from the Marin Shakespeare Company. Each of the thirteen stories performed also relayed intimate aspects of the author’s life and experiences. Some spoke about the pain of losing loved ones to gun violence, while others addressed the effect of having no positive role models growing up.

Once the thick layer of fog that had settled over the prison lifted Friday morning, prisoners were permitted to leave their cellblocks and the ninety civilian guests who had received clearance to enter the complex made their way to the Protestant Chapel with other inmates to watch the performance. Afterward, many of the civilians in the audience described the show as an eye-opening experience, while several of the inmates who attended said they were inspired to try out for roles in next year’s play.

San Quentin — once known as one of the toughest prisons in the nation — has more than sixty volunteer, leisure, and self-help programs for inmates, including education and art classes and the only inmate-produced newspaper in the state. “San Quentin is unique among state prisons,” said Lesley Currier, co-founder of the Marin Shakespeare Company, who produced and co-directed Friday’s performance. “It’s really a testament to being here in Bay Area, where so many people care and want to make a positive difference.”

Currier and her husband, Robert Currier, started the Marin Shakespeare Company 25 years ago, with the mission of using Shakespeare as a way to educate and heal residents in Marin County and the surrounding Bay Area. With that in mind, they eventually turned their attention to the rocky outcrop jutting off of Marin’s eastern shore into the San Francisco Bay.

“We looked at San Quentin as a place where Shakespeare could be a transformational tool, where people would not otherwise have that opportunity,” Currier said.

Inspired by the success of similar prison theater programs in other parts of the country, Shakespeare at San Quentin began as a weekly meeting with a group of prisoners in 2003. At first, the men would perform short scenes and sonnets. Actors from the Marin Shakespeare Company would come in to perform and work with the inmates. Licensed drama therapist and actress Suraya Keating took over as lead teacher and director in 2007. The next year, the men performed their first full-length Shakespeare play, the comedy Much Ado About Nothing. Last May, the group performed its sixth play, The Merchant of Venice.

Keating added the parallel plays to the program’s curriculum as a way for the men to use themes from Shakespeare as a lens through which to examine their own lives. Keating said pushing them to be creative encourages them to connect with themselves and the rest of the group in a way they never thought possible.

“In the telling, and even more in the witnessing, of these stories, there’s a way things can move and shift that were holding us back before,” Keating said. “When we’re not heard, we either tend to act out and get really angry or act in and get really anxious.”

Friday’s performance dealt with four themes: hate, different perspectives, love, and forgiveness. Using spoken word and original songs, the men examined past relationships and choices they had made. John Neblett, who is serving his 28th year of a life sentence for second-degree murder, performed a piece based on his relationship with his father and inspired by the poems of John Donne. A piece written by Ron “Yana” C. Self and Julian Glenn Padgett presented a dramatic examination of post-traumatic stress disorder and veteran suicide through the perspective of Yana’s experiences as a Marine during and after combat.

With only ninety days left in his nine-year sentence, Tristan Jones shared what the Shakespeare program has meant to him, and how it felt to leave behind the group that had become his family. “Their love and loyalty belongs to me when I go, and mine belongs to them,” Jones said during a question-and-answer session after the performance. He added that he hopes to continue sharing what he learned from the program after his release by continuing to practice acting and improvisation.

Funding Shakespeare at San Quentin is no easy task, Currier said. Although prison administration is supportive of the program, the state provides no monetary backing. Previously, the California Department of Corrections’ Arts-in-Corrections office provided staffing for arts programs in state facilities, but contracts were terminated in 2003 during a state budget crisis. Over the years, Keating and Currier have managed to secure small grants and individual donations to finance their work. This year’s performance was funded by Cal Humanities, the Rosenberger Family Fund, and the William James Association. Despite its state of financial uncertainty, the program was expanded this year in response to the high level of interest, effectively doubling expenses, according to Currier.

Still, Keating and Currier insist that the benefits far outweigh the costs. USF Professor Larry Brewster has been studying the effects of arts instruction on inmates’ attitudes, behavior, and identity since the 1980s. His research has shown that the longer inmates are enrolled in arts programs, the more likely they are to show improvement in areas such as self-confidence, social interaction, and discipline. In a 1983 cost-benefit analysis of arts-in-corrections programs at San Quentin and three other prison facilities, Brewster found a 75 percent reduction in disciplinary action among inmates involved.

Efforts to promote art programs based around the rehabilitative powers of Shakespeare are not limited to California. This week, Currier will attend the first-ever Shakespeare in Prisons Conference at the University of Notre Dame, where artists and educators from around the world will discuss successful methods for promoting self-awareness and healing using theater and creative writing.

So far, Shakespeare at San Quentin has seen three of its participants released back into society. John Wilson, who was released in March after serving fifteen years, said his roles in Hamlet and Twelfth Night and his experience writing a parallel play forced him to evaluate himself and change the way he interacted with the world. “People say they can’t act, but when you look back at your life you wear many different faces,” he said. “For me, Shakespeare allowed me to be a little bit versatile and see the humor in life.”

Wilson said he hopes to eventually go back to prison — this time as a volunteer. “Those of us who have been through something, we owe it to the ones we left behind to show people what a convict is not.”