It’s also an exceptionally well-produced portrait of the American experiment, warts and all. Peck, a native of Haiti raised in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, is a dedicated leftist who once served as Haiti’s Minister of Culture, and is now the president of La Fémis, the French national film school. His movies, including Lumumba (2000) and Profit and Nothing But! Or Impolite Thoughts on the Class Struggle (2001), are certified political fire-starters, not exactly the type of entertainments that would be expected to sell tickets in American art houses. But to truth-seekers and skeptics they’re pure catnip. When it comes to exposing social injustice, Peck’s films tend to get right to the point.

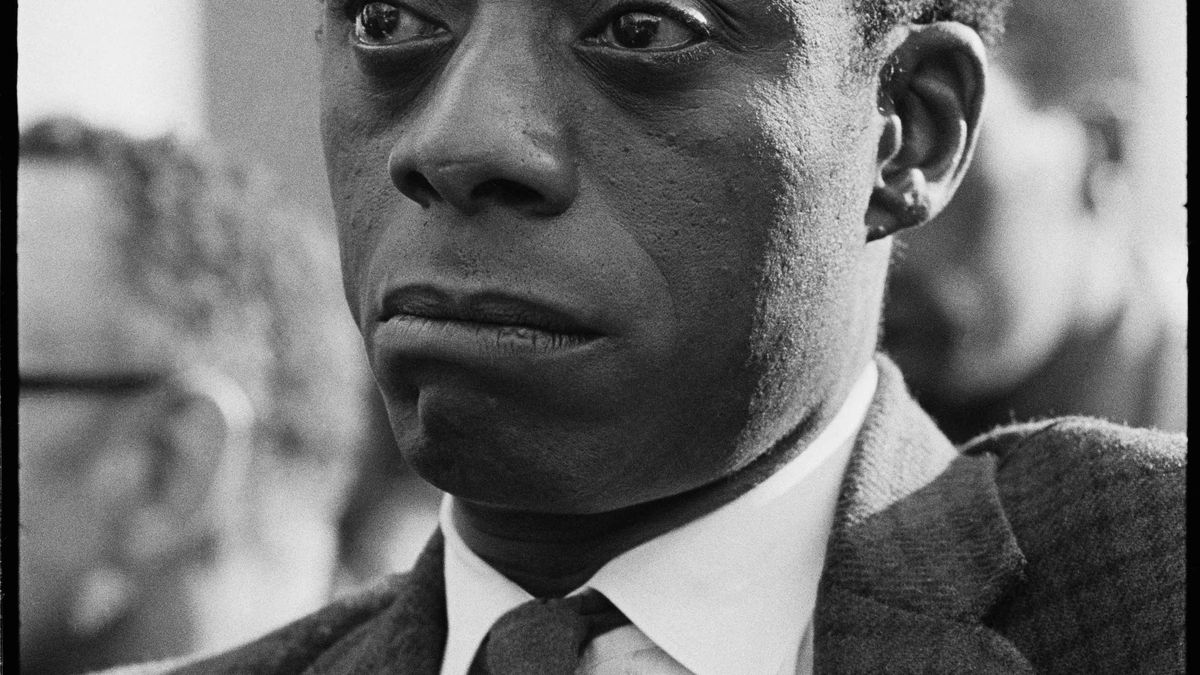

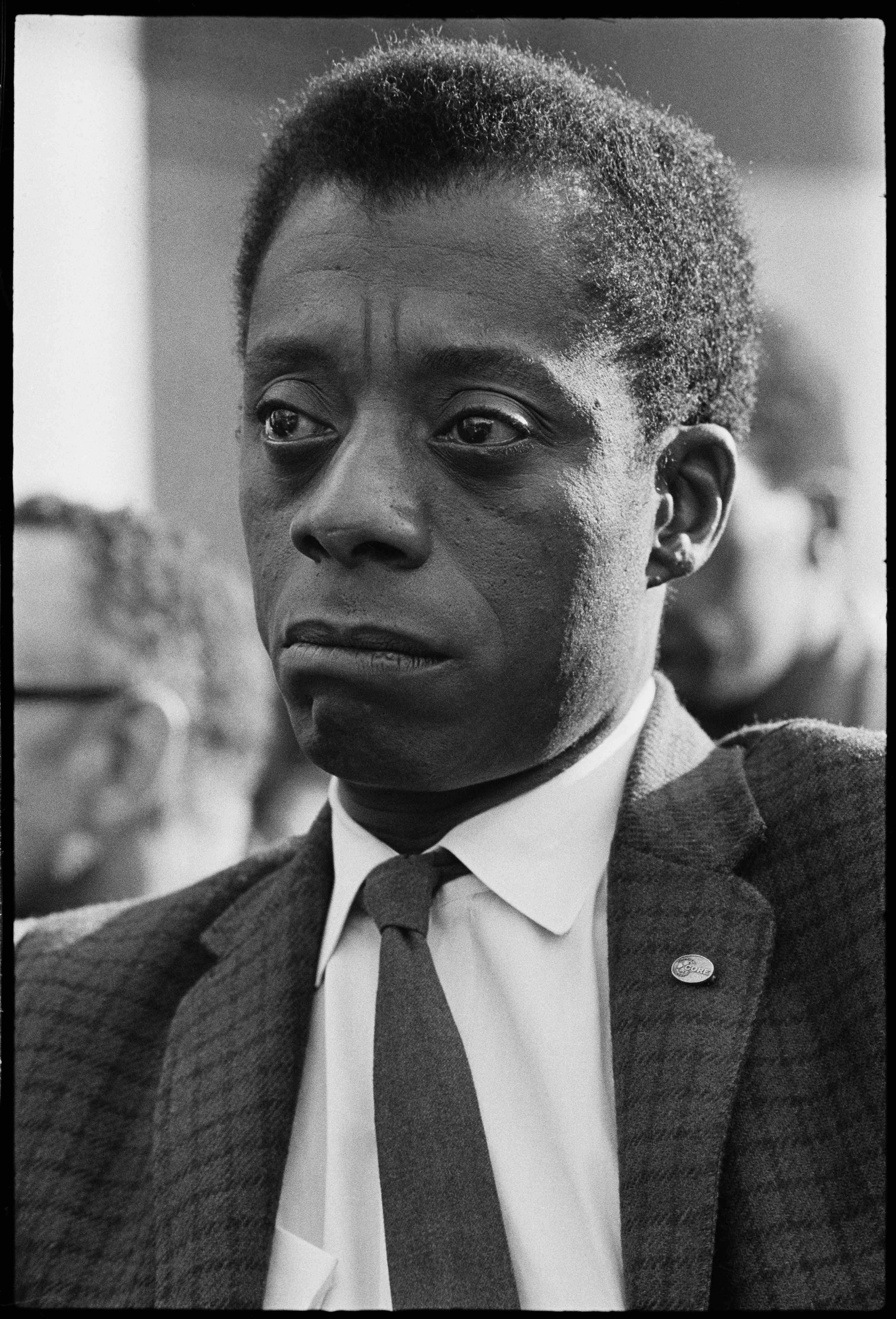

That investigative zeal also describes the life and career of James Baldwin (1924-1987). The gadfly author of The Fire Next Time and Notes of a Native Son was the outcast’s outcast on the New York-Paris literary scene, a gay Black intellectual whose lifelong subject was the struggle of the human spirit against oppression. Peck’s doc is based on Baldwin’s unfinished book Remember This House — at his death he had completed only thirty pages, but they reflect Baldwin’s characteristically dry, acerbic wit as he comments on his times.

The film is a remarkably well knit panorama of the “other side” of Sixties and Seventies America, in the context of this country’s ongoing agony over race, as seen in the interrupted lives of the three most influential Black leaders of their day: Medgar Evers, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and Malcolm X. All were murdered before their time. A document of bewilderment and hurt, this project is bathed in flames.

Baldwin and Peck argue persuasively that Black people in this country have been kept down for 400 years, buried beneath a mound of hatred and neglect. The montage of violence and humiliation in the film is relentless. Vintage newsreels take us to the Little Rock, Arkansas, school desegregation confrontation in 1957, where armed federal marshals escort Black kids to classes. We witness police dogs sicced on civil rights marchers; a parade of demeaning advertising images; children staring straight into the camera; the infamous video of the Rodney King beating which magically segues into a fruity scene from Love in the Afternoon, a romantic Hollywood fantasy of love between white people; urban riots (and heavily armed response) in Los Angeles and Ferguson; and ugliest of all, the bodies of lynching victims swinging from trees, surrounded by crowds of white men with a strange look on their faces. These images are shocking, but Baldwin informs us that Black people have been living with this for centuries. “White people are astounded by Birmingham,” he writes. “Black people aren’t.”

Baldwin indicts the dominant culture in no uncertain terms: “I know very well that my ancestors had no desire to come to this place. But neither did the ancestors of the people who became white, and who required of my captivity a song. They require a song of me, less to celebrate my captivity, than to justify their own.” The notion that America’s white culture is guilty of enslaving not only Blacks but everyone else in it, is illustrated again and again in the doc — most unforgettably in a fantasy scene from the 1957 movie The Pajama Game, in which a crowd of impossibly joyous white men and women come running and tumbling across a sunny summer landscape, giddy with happiness.

Over that scene float Baldwin’s words: “For a very long time America prospered. This prosperity cost millions of people their lives. Now, not even the people who are the most spectacular recipients of the benefits of this prosperity are able to endure these benefits. They can neither understand them, nor do without them. Above all, they cannot imagine the price paid by their victims or subjects for that way of life. And so they cannot afford to know why the victims are revolting.”

These words, along with all the spoken language in I Am Not Your Negro, are intoned in an eerie, controlled whisper by actor Samuel L. Jackson. Baldwin’s outraged candor is meant to sting, and even thirty years later it does. Peck’s mise-en-scene makes sure of that, aided by Alexandra Strauss’ film editing and Alexei Aigui’s music score. Movies generally thrive on make-believe. Everything in Peck’s film, however, is utterly real.

One sequence is particularly haunting. It shows King being taunted and spat upon by a snarling mob of white youths in the Chicago neighborhood of Marquette Park in 1966. King was protesting housing segregation, and many of his tormenters sported swastikas. King was hit by a thrown rock, and if the police weren’t there they might have killed him. As a white native of Chicago revisiting this TV news footage after many years, I can only ask myself: “Who are these haters? Where did they come from?” And the only answer that fits is that they are ordinary scared Americans like everybody else. That’s a dismal thought to deal with, especially in the winter of 2017. See I Am Not Your Negro and let’s try to pick up some knowledge.