Jerry Brown considers the Oakland School for the Arts and the Oakland Military Institute to be among his signature achievements as mayor of Oakland. But one decade after he founded the schools, their test scores remain less than stellar despite the fact that the two schools spend far more money educating students than other Oakland public schools.

Brown’s prowess as a fund-raiser has allowed the schools to spend $10,000 to $12,000 a year per student over the past several years, according to tax returns filed by the arts and military schools. By contrast, Oakland’s public schools and most of its other charter schools receive about $6,000 to $8,000 per student in local, state, and federal funding, along with parent donations, according to data from the Oakland Unified School District.

Yet considering the resources at their disposal, the Oakland School for the Arts and the Oakland Military Institute have been uninspiring in terms of test scores. Last year, for example, the Oakland School for the Arts scored a 723 on the state’s Academic Performance Index and the Oakland Military Institute posted a 708. Although the results were respectable, they’re by no means excellent. The state considers a good score to be 800 or higher. “You’d think their test scores would be through the roof,” said Oakland teachers’ union president Betty Olson-Jones. “It begs the question — where is all the money going to?”

Neither Brown nor spokespersons from his office returned phone calls seeking comment. But Donn Harris, executive director of the Oakland School for the Arts, and Mark Ryan, superintendent of the Oakland Military Institute, maintained that their programs, which both include sixth through twelfth grades, should be judged by more than just test scores.

They each make valid points. But even if one agrees that the schools have value beyond academics, the millions that Brown has raised for them undercuts one of the main arguments the former mayor made for opening them in the first place. Back in 2000, and in the years since, Brown has maintained that the two charter schools would serve as examples of how public schools should operate. In fact, his experiment does not appear to be replicable in any significant way. What other schools, after all, have a former ex-governor, and possible future one, hitting up wealthy donors on their behalf?

The amount of money Brown raises for these two schools makes it impossible to compare his schools to regular public schools, while at the same time raising questions of equity. A hallmark of public education in California is that all schools spend about the same money per student. But the arts and military schools spend up to twice as much on each of their kids than other Oakland public schools.

Since being sworn in as California attorney general in January 2007, Brown has solicited more than 400 separate donations for his two schools, totaling $11.8 million, according to reports filed with state Fair Political Practices Commission. The contributions came from big corporations, well-funded foundations, and wealthy individual donors, including many donations from his stable of political campaign contributors. The Oakland School for the Arts received $7,739,612 in donations that he solicited, while the Oakland Military Institute got $4,092,200. The huge donations are unusual in the world of charter schools, where many campuses struggle just to make payroll and rent.

So does Brown’s educational experiment prove that throwing money at California public schools isn’t the way to raise students’ academic performance? Or does it say more about the former mayor’s failings as a manager? After all, public schools in other states that receive about the same amount of money as his school — such as in New York — tend to perform better academically. And Brown’s hands-on approach to his schools is not constricted by collective bargaining agreements, because both the arts and military schools are non-union.

One thing is for sure: Brown’s arts school is not spending huge sums trying to educate children from difficult backgrounds — at least not compared to most Oakland public schools. Just one-third of the arts school students last year qualified for free or reduced-price lunches, a standard measurement of poverty level. By contrast, about 68 percent of students in the Oakland public school district qualify for such lunches, and at the Oakland Military Institute, the percentage was 77 last year.

The arts school’s primary goal is nurturing young artists. To gain entrance to the school, kids must audition in their artistic field of choice, and the administration asks nothing about academic ability, Harris said. “They come in with all different levels,” he explained.

Before Brown recruited him to the school, Harris ran an arts magnet in San Francisco. Harris also says that Brown keeps close tabs on the school and calls him often. Harris also candidly acknowledged that the school has needed all the money raised by its influential benefactor. “It’s really necessary to run a world-class arts school,” he said.

The school spends significant sums on arts instructors — an expense that most California public schools now view as a luxury. And by most accounts, Brown’s school excels as an arts magnet. “It’s a robust program,” Harris added.

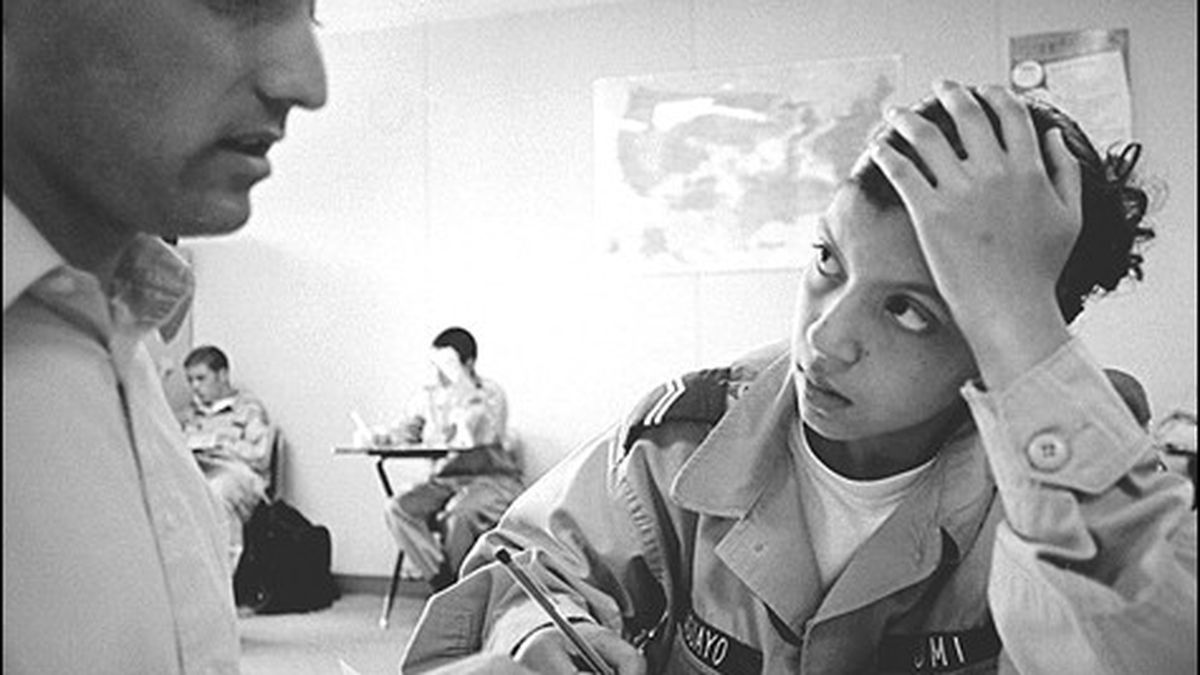

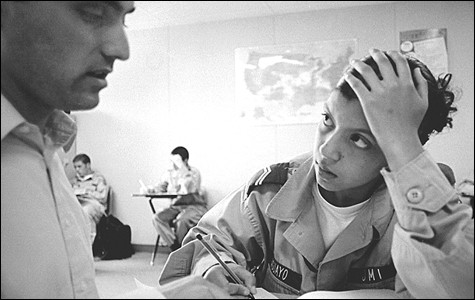

As for the military institute, Ryan said its main goals are to teach kids discipline, keep them out of trouble, and put them on track for college. And he noted that his school has a better graduation rate than other Oakland public high schools, and that 95 percent of the school’s graduates go on to college, including 70 percent to four-year schools. Still, he acknowledged that the school’s test scores are not what he wants them to be. “We need to be doing much better,” said Ryan, who also is a lieutenant colonel in the California State Military Reserve.

Like Harris, Ryan said the military school needs all the money it receives from its rainmaker, although both said they hope to be more self-sufficient in the future.

In addition to the $1 million in annual donations that Brown raises for the military school, it receives $130,000 a year from the California National Guard to pay for military personnel on campus, along with student uniforms, Ryan said. The school also qualifies for federal funding earmarked for students in poverty.

The military school also enjoys what amounts to almost free rent from the Oakland public school district at the former Longfellow Elementary School in North Oakland. The deal, which was signed by former state Administrator Kim Statham, only requires that the school perform up to $250,000 a year in property improvements, which is no problem because of the donations Brown solicits.

“It’s a sweetheart deal,” said school board member David Kakishiba, who opposed the military school’s rental agreement when it was inked three years ago. “We don’t have a deal like that with any other charter school.”

Meanwhile, the arts school benefits from billboard deals that Brown brokered with the city, the Port of Oakland, and CBS Outdoor. One of the billboards helped provide the seed money for the city-financed restoration of the Fox Theater by Oakland developer Phil Tagami. The billboard’s revenues also allow the arts school to occupy more than 60,000 square feet inside the Fox — or about 46 percent of the building — rent free. As for the second billboard, it generates a minimum of $157,000 annually for the school, according to public records.

Harris said the school spent about $5 million of what Brown raised on “tenant improvements” inside the Fox to turn it into classroom and art studio space. The school also received a $2.3 million loan from the city for those improvements. The rest of the money Brown raised went to the school’s arts and education program.

All that additional money also has made the schools popular with parents, who clamor to get their kids enrolled. The military school, for example, uses a lottery system to deal with all the applications.

“I feel great for these kids and their families; I don’t begrudge it,” said former longtime Oakland school board member Greg Hodge. “When I talked to Jerry about it, he said, ‘We’re doing this great work. We’re getting these great outcomes. We’re showing how the system should be operating.’ But what he’s really showing is the amount of money you need to educate kids. If Jerry really wants to do something revolutionary as governor, he should be a proponent of reforming school financing.”

Of course, as a politician whose distaste for traditional public schools is well-known, Brown likely will not advocate to fund public schools like his charter schools are funded — especially not in a year when the backlash against government spending appears to be growing. It also seems clear that Brown is unlikely to trumpet the real lessons learned from his arts and military schools — that is, management ability counts and money isn’t always the answer.

Nonetheless, if the former mayor wins the governor’s race, the arts and military schools will probably continue to receive millions in extra funds not available to Oakland’s other 100-plus public campuses.