On a rainy December day in Emeryville, organizers distributed umbrellas to a small crowd chanting and yelling at cars in front of the Woodfin Suites Hotel. Half the picketers were church people, community activists, or union folks — the sort who turn out for many demonstrations, rain or shine. The other half had just gotten off work. Some held animated discussions as they walked up and down the wet sidewalk in their gray uniforms. But most just looked tired at the end of another long day.

Under one umbrella, Luz Dominguez, a Mexican woman in her forties, huddled against another housekeeper from the towering hotel looming above them. Dominguez and her colleagues were already dreading the next day, when they’d once again put on their uniforms and make the trek to Emeryville to clean hotel rooms. “I feel really exhausted at the end of my shift,” she said with a sigh. “When I get home, I have no energy for my family. All I do is worry about what the next day’s work will be like — if the rooms will be the same, or even more dirty.”

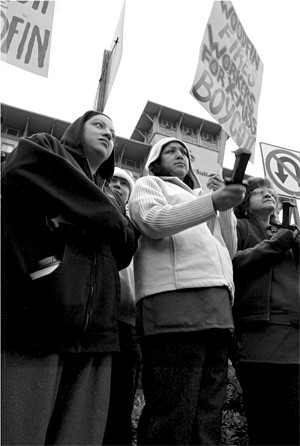

Woodfin Suites housekeepers protest their pre-Christmas firing. Credits: David Bacon

Housekeeping work is exhausting. (Note: This photo was not taken at Woodfin Suites.) Credits: David Bacon

“A Social Security number cant wash toilets or vacuum floors or make beds,” Dominguez says. “Only human beings can do that.” Credits: David Bacon

A judge ordered Woodfin to reinstate the workers temporarily, but their jobs are hardly secure. Credits: David Bacon

You wouldn’t think anyone would want to keep a job that leaves her feeling that drained, but Dominguez and twenty co-workers have been fighting for exactly that all fall and winter. Their pre-Christmas picket line was just their latest effort to keep the hotel from firing them. Their jobs are worth keeping partly because of a new ordinance intended to lighten the workload that leaves them exhausted each day. But just as the law seemed to promise the workers more time and money for themselves and their families, the women have found themselves at the center of a national firestorm over immigration.

On December 15, a few days after the picket line, hotel managers sent Dominguez and her friends home for good. The workers were just 21 of the thousands of people fired, and in some cases deported, in the Bush administration’s fall offensive to root undocumented workers out of workplaces. A November action targeted workers at the largest industrial laundry in the United States. In December raids at six Swift meatpacking plants, more than 1,300 laborers were detained and deported.

The firings and deportations did not directly affect most of the twelve million people now living in the United States without immigration papers. But they did make a political point. In a Washington press conference, Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff told reporters that such enforcement efforts highlight the need for “stronger border security, effective interior enforcement, and a temporary-worker program.” He took the opportunity to promote the president’s proposed guest-worker program, which stalled in Congress last year.

But labor and immigrant-rights activists see another motive. They say the firings targeted workplaces where people were organizing unions, trying to enforce labor-protection laws, fighting to improve wages or benefits, or otherwise standing up for their rights.

Emeryville’s Woodfin Suites has become a poster child for these accusations.

In November 2005, Emeryville voters passed a worker-protection ordinance known as Measure C. The measure was the brainchild of the East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy, a worker advocacy group that represents a new kind of thinking in labor. EBASE, as it is known, brings together union and community activists in a permanent coalition. Its young organizers are labor’s shock troops, turning out for demonstrations, exposing worker abuse, and campaigning for living wages throughout the East Bay.

It was no accident that the group set its sights on Emeryville, a small town originally carved out as a tax-free haven for big factory owners. Those plants are long gone, and in their wake, the city at the foot of the Bay Bridge toll plaza has reinvented itself as a home for hotels, malls, and loft apartments — businesses that all rely upon immigrant labor.

“The old guard was very business-friendly and gave the developers whatever they wanted,” said city council member and lawyer John Fricke, who sees himself as part of the new Emeryville. “But the people who came to live in the new lofts and apartments are young people priced out of San Francisco. They have a pretty supportive attitude toward workers and immigrants.”

EBASE organizers looked at these new demographics and predicted that Emeryville would take to heart the plight of its primarily immigrant hotel workers. They collected signatures for a living-wage ordinance that would mandate a $9 hourly minimum, and an $11 average, in each of Emeryville’s four hotels. Any housekeeper required to clean more than five thousand square feet in an eight-hour shift would earn time and a half.

The city’s hotels — Holiday Inn, Marriott Courtyard, Sheraton Four Points, and Woodfin Suites — all opposed the ordinance. Under the name of the Committee to Keep Tax Dollars in Emeryville, they spent $115,610 for an election in which only 2,296 people voted. The committee spent $110 for each “no” vote cast, but the ordinance prevailed 1,245 to 1,051. Afterward, the hotels tried but failed to prevent the measure’s implementation with a court challenge.

Over the following spring and summer, EBASE organizers met with workers at the four hotels and explained the law’s new requirements. Marcela Melquiades, who had been cleaning rooms at Woodfin Suites for two years, recalled what life was like before Measure C. “The workload was very heavy,” she said. “I’d be really tired at the end of the shift. I’d go to the bathroom right away and pour hot water on my hands. I still had to go home, make dinner for the kids, clean the house, get my uniform ready for the next day, get up early in the morning. It was exhausting.”

But Melquiades and her friend Dominguez believed Measure C would make things better for them and their co-workers. “Before it was approved, we cleaned sixteen suites a day, sometimes seventeen.” Dominguez said. “A suite is made up of a bedroom, a hall, and a kitchen. We’d clean the whole thing in thirty minutes. When people would party and leave it dirty, we’d still have to clean it in that time.”

Following the passage of Measure C, Woodfin Suites general manager Hugh MacIntosh said the hotel changed its cleaning regimen to comply with the ordinance. “We reduced the rooms cleaned per day from seventeen to 10.5, which is within the five-thousand-square-foot limit,” he said. EBASE organizers say the correct number of rooms should be eight or nine. Still, there was no question that Measure C had transformed the housekeepers’ jobs.

Then, in September, the hotel began accusing longtime workers like Dominguez and Melquiades of not having valid Social Security cards.

To get a job, everyone living in the United States must complete an I-9 form, which must be accompanied by two pieces of identification, including a Social Security number. The form asks applicants to state whether they are citizens or legal residents. All the hotel’s workers had long ago completed such paperwork and gone to work without objection or complaint. But on September 27, Dominguez, Melquiades, and nineteen others were given a letter by Mary Beth Smith, the hotel’s director of human relations, saying they had 24 hours to provide valid Social Security numbers or they’d be fired. Smith isn’t at the hotel anymore, but the chain of events her letter set in motion is far from being settled.

The Social Security Administration writes to thousands of businesses every year, listing the names of hundreds of thousands of people whose numbers don’t jibe with those on file. In 2001, the agency sent out 110,000 such letters. After September 11, the number of such notices mailed increased severalfold.

There are many reasons a worker’s Social Security number might not match government records. Some are undoubtedly the victims of clerical errors, since the government’s database is notoriously full of errors. But other workers, including many of the millions who are in the United States without proper documentation, make the list because they used a nonexistent number, or one that belongs to another person.

In the recent raids at the Swift meatpacking plants, the Bureau of Immigration and Customs Enforcement called such use identity fraud. But using someone else’s Social Security number to get a job is hardly the same as using his or her credit cards to purchase expensive stereo equipment. There is no evidence to suggest that the genuine holder of a Social Security number is harmed when someone else uses that number on the job. After all, an employer will be depositing extra money into that person’s account, and the worker using the incorrect number will never be able to collect the benefits those earnings will accrue.

The Bush administration has been using these letters to pressure employers to fire workers they suspect of lacking visas, and hopes to make such terminations mandatory. Today, however, there is no such requirement. In the late 1990s, protests by labor and immigrant-rights activists forced the Social Security Administration to include a crucial paragraph in the no-match letters, cautioning employers not to construe a discrepancy in numbers as evidence of lack of immigration status. Employers are asked only to advise workers they’ve received such a notice.

After all, the Social Security card is not a national identification card. In the United States, unlike other countries, there is no national ID card, nor any obligation requiring residents to possess one. In fact, every time a bill to create a national ID has been proposed in Congress, it has failed.

“The law requires that, for an individual to work, they have to complete the I-9,” Woodfin’s MacIntosh said. “That requires the workers to provide a valid Social Security number. We’ve simply asked them to get a document from SSA saying they’ve completed the I-9 requirements.”

But once an employer accepts an I-9 form and an employee goes to work, the employer can’t later ask the worker to reverify that information. Such reverification has been viewed by the Department of Justice as discrimination, which is prohibited by the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986. EBASE has not challenged the firings on this basis. But Marielena Hincapie, staff attorney for the National Immigration Law Project, said reverification as a result of a no-match check also is a violation of section 274-B of the Immigration and Nationality Act. Congress expressly included this prohibition out of concern that reverification would lead to discriminatory worker dismissals.

Labor advocates see another motivation at work. In the legal proceedings surrounding the firings, Woodfin Suites revealed that it had received a letter about its workers’ Social Security numbers in May 2006. But managers took no action until September, after employees had complained to the city council that the hotel wasn’t abiding by Measure C. Woodfin gave a series of deadlines to the workers, which it extended under community pressure. Finally, it lowered the boom on December 15.

Dominguez believes she knows why she and her co-workers were dismissed: “The reason the hotel was saying this was because we were demanding our rights.”

Emeryville’s housekeepers don’t actually live in Emeryville. Many live in Oakland’s Fruitvale district, the largest Latino barrio in the East Bay. For Dominguez and Melquiades, home is a gray, two-story apartment complex. Outside, along International Boulevard, signs in market windows list groceries in Spanish — chiles, tortillas, mangoes, and the other comfort foods of Mexico and Central America.

Dominguez’ small two-bedroom unit isn’t stuffed with furniture. A couch and fold-out futon in the living room face a console with a TV and boom box. A huge stuffed floppy dog lies on the futon; atop the television, a big white stuffed bear with red satin hearts instead of paws holds two more red hearts stitched with the word amor — Spanish for love. Christmas lights around the front window give the room its illumination.

The Fruitvale isn’t really like Mexico, but there are enough Mexicans living there for it to feel like home. “You feel good here, but there’s no work,” Dominguez said. “You have to leave to find a job. That’s why we go to Emeryville.”

When Luz Dominguez first came to Oakland in 1995, she didn’t know anything about any of the cities of the East Bay — not even the one where she was living. “It was very hard to find work,” she remembered. “I would just walk up one street and down another, asking anyone I met, people I’d never met before. If I didn’t have any luck on one street, I’d just go on to the next. It hurt, and I was ashamed. But you always have to think, ‘I’m going to find a way.’ If you get negative, it paralyzes you.”

Eventually, she learned enough about her new home to begin finding cleaning jobs, which eventually led her to the Woodfin. That’s where she met Marcela Melquiades, who grew up in a neighboring town on the fringe of Mexico City. Neither knew many people in Oakland, or had an extended family in the United States. Melquiades came here at age nineteen with her husband. They later separated, leaving her a single mother of three children aged eleven, eight, and seven. Now she lives next door to Dominguez.

“We share memories of the food and the places we both remember, and forget our problems for a little while,” Dominguez explained. “We’ve become good friends.” The two women are fifteen years apart in age, but they laugh and put their heads together and their arms around each other as though they were classmates in high school.

When she arrived in Oakland eleven years ago, Melquiades didn’t intend to stay long. “For a while, we came and went,” she recalled. “Like every immigrant, you always think at first that you’re going to make life better at home — build a house or start a business. But time passes. You realize you can live better here, and you forget about your old goals. And you stay.”

But she also had difficulty finding a good job, and having young children didn’t make it easier. “Everything was new and strange,” she recalled. “You don’t know how things work. You don’t know anyone. You have to ask about everything: doctors, school, whatever.” She worked one Christmas in a factory, making tree ornaments. Other years she was a domestic. Eventually, she, too, got work in hotels. “I don’t like kitchens or restaurants,” she said with a laugh. “I like cleaning.”

Eventually, Dominguez and Melquiades came to feel comfortable working at Woodfin Suites. For years Smith and other managers had been watching the housekeepers make beds, wash toilets, vacuum carpets, and clean up after messy guests. “I thought I had a place where people knew my work and respected me,” Dominguez said. “When I first started working they didn’t give me gloves, and I still cleaned the sinks and the toilets. I pulled garbage from the trashcans with my bare hands. I never said, ‘If you don’t give me gloves, I won’t do it.’ I needed a job, and I wanted to work.

“I felt appreciated,” she continued. “Guests would say, ‘Doña Luz, you’re doing a great job.’ I didn’t care if they left me tips. In 2005 the hotel even gave me their Employee of the Year Award. So when they began demanding the card, I felt destroyed inside. I cried. I said to myself, ‘How can you ignore all the good things I’ve done?'”

The two housekeepers declined to specify their immigration status for this story. But when Dominguez describes what happened at the hotel, she is still so angry that her voice trembles. “She told us we’d have to show her our Social Security cards so they could check the numbers,” she recalled bitterly. “Before, they’d tell us sometimes they’d received a notice about our numbers not matching, but they never required us to take any action, or told us we couldn’t continue working.

“A Social Security number can’t wash toilets or vacuum floors or make beds. Only human beings can do that. Legal documents are very important, but real, physical work is what counts.”

The Woodfin firings highlight the vulnerability of undocumented workers under current US immigration law. That increased in 1986, when Congress passed the Immigration Reform and Control Act, making it a federal crime for an employer to hire workers without valid immigration documents. But by making it illegal for the employer to hire, the law also made it a crime for those workers to hold a job.

Twenty years later, the no-match letter has become a way for the administration to enforce that prohibition with the help of the Social Security Administration.

As workers were battling with hotel managers at Woodfin Suites, others found themselves in the same predicament. In November, nearly four hundred workers in laundry plants across the country were pulled off their jobs after they’d received letters from their employer, Cintas Corporation, advising them of a no-match check. Cintas is the largest industrial laundry in the United States, with four Bay Area locations. Elena, an immigrant working in its San Jose facility, told the San Jose Mercury News that “I feel that this is discrimination because we were helping with union organizing.”

For the last two years, UNITE HERE, the union for hotel and laundry workers, has mounted a national campaign to organize Cintas, marked by firings and charges of unfair labor practices. The company claimed that the no-match terminations were done to comply with a new requirement by the Bush administration. “All employers have a legal obligation to make sure that all employees are legally authorized to work in the US,” Cintas spokesman Wade Gates told the Mercury News.

Other companies firing workers for the same reason this fall include Smithfield Foods, which has battled an organizing drive by the United Food and Commercial Workers for a decade, and Aramark, which has a national union contract with UNITE HERE. All used the same justification — that they were simply abiding by a proposed rule change by President Bush that would require employers to fire anyone named in a Social Security no-match letter.

There’s only one problem with that argument: That rule change was never issued. Because its implementation would undoubtedly cause a huge outcry, the president has waited for enactment of a larger immigration-reform program.

According to an estimate by the Pew Hispanic Trust, a Washington, DC, foundation, about twelve million people living in the United States lack immigration papers. The vast majority are of working age, and since no one without documents can get public assistance, it’s safe to assume that most are employed. To get their jobs, almost all have provided Social Security numbers that don’t belong to them.

If these millions of people were identified and terminated, as Bush’s rule would require, it would have an enormous economic impact on the nation. Crops would rot in the fields. Restaurants and hotels would be forced to close. The production lines in meatpacking plants would cease from lack of workers. Housing construction would grind to a halt.

Immediate and widespread enforcement of the rule would deprive employers of a massive, undocumented workforce they’ve grown to depend upon. But the administration’s program for immigration reform doesn’t simply propose to drive people with papers out of the workplace. It also aims to replace them with a new flow of labor, recruited and brought into the country on temporary visas to fill contract jobs.

The president’s proposed regulation has its roots in a political deal advanced by the Essential Worker Immigration Coalition, an association of forty of the largest manufacturing and trade groups in the United States, which represents companies such as Marriott, Tyson Foods, and Wal-Mart. Two years ago, Senators Edward Kennedy and John McCain introduced a bill that would have permitted many undocumented immigrants to seek legal status, while giving large employers the power to bring four hundred thousand additional workers a year into the United States on temporary work permits. It would have required undocumented people already here to declare their presence and spend eleven years as contract workers before they could apply for citizenship.

The bill would have increased enforcement of employer sanctions, proposing the same raid and no-match strategy the government is using today. When the Senate and House couldn’t reconcile their conflicting bills, the president then proposed but did not implement his own regulation increasing workplace enforcement.

Observers expect the Kennedy-McCain bill to be reintroduced into Congress this year. Most unions opposed it last time because they do not favor guest-worker programs and also because it strengthened employer sanctions, making the raids and no-match checks possible. The AFL-CIO also wants to give undocumented immigrants legal status.

Bruce Raynor, president of UNITE HERE, said the no-match letters are an indication of what’s wrong with the law. “There are twelve million undocumented people living here who are important to the economy,” he said. “They have a right to seek employment, and employers have a right to hire them. The only way to deal with this is to give workers rights and a path to citizenship.”

Nevertheless, both Raynor’s union and the Service Employees International Union, another union with many immigrant members, supported the Kennedy-McCain bill, while the rest of labor opposed it. “We thought it was what was possible under those circumstances,” Raynor said. Increased employer sanctions and guest-worker programs were a price they were willing to pay for legalization of the undocumented.

Since then, however, the raids have caused many onetime supporters to question that decision. Just last week, for instance, the SEIU reversed its position and now opposes worker sanctions and most forms of guest-worker programs. EBASE organizer Sarah Norr notes that sanctions don’t stop employers from hiring undocumented workers: “They just create sort of a revolving door, where they can be hired and then gotten rid of if they stand up for their rights,” she said.

Congress’ new Democratic majority is divided. Last year, Democrats Silvestre Reyes, a former Border Patrol agent, and fellow Texan Charles Gonzalez introduced a bill paralleling Bush’s regulation. They argued that supporting hard enforcement is the secret to winning the 2008 presidential election. Incoming House Speaker Nancy Pelosi named Zoe Lofgren of San Jose, a strong defender of Silicon Valley’s high-tech guest-worker programs, to head the House Immigration Subcommittee.

Progressives such as Oakland’s Barbara Lee believe the November election makes other alternatives possible. The Oakland-based National Network for Immigrant and Refugee Rights has proposed one such alternative. It convinced the AFL-CIO and dozens of local immigrant-rights coalitions to sign a petition calling for legalization of the undocumented, more opportunities for legal immigration, no new guest-worker programs, and an end to employer sanctions and militarization of the border.

It is unlikely that even the new Democratic majority would pass such a bill. But if such a proposal were to become law, workplace raids like those at Swift and mass dismissals like the one at Woodfin Suites would become a thing of the past. Workers without papers would be able to begin a process leading to permanent visas and citizenship.

If, on the other hand, Kennedy-McCain is reintroduced and passed, Woodfin Suites will be forced to fire Luz Dominguez, Marcela Melquiades, and the other workers named by Social Security. People without papers may be able to sign up as guest workers to keep cleaning rooms, but they’ll lose their immigration status if they lose their jobs.

Within a week of the firings at Woodfin, EBASE and the Emeryville city attorney went to court seeking an injunction returning the housekeepers to their jobs. The city argued that it needed their presence until it could investigate whether the firings were retaliatory.

“It is very important for the city to keep the workers employed until it can determine whether their allegations of retaliation are bona fide,” Fricke said. The councilman added that he asked the hotel’s manager if federal authorities were demanding that it terminate the workers. “He said no. Our problem is that if the city council allows an employer to threaten workers — although the hotel says it’s acting for some other reason — this has a strong, chilling effect on the willingness of others to come forward and report violations.”

Hotel manager MacIntosh denies that the hotel is retaliating for the workers’ efforts to enforce Measure C. “We’d like to see them come back,” he said.

Shortly after New Year’s Day, once Alameda County Superior Court Judge Ronald Sabraw ordered the hotel to reinstate them, Dominguez, Melquiades, and nineteen other housekeepers returned to the hotel. But the women feel caught between their need for employment and their growing unease about the immigration climate.

After work one December night, with her family fed, Dominguez and her friend sat at the Formica table in Dominguez’ kitchen. On the table, cups of cinnamon tea rested on a little white doily alongside a plate of tiny white guava-jam sandwiches with their crusts cut off. It was like an English tea party with a Mexican flavor. Drinking tea, the two mothers remembered home.

“My father taught us to work,” Dominguez recalled. “‘We are working people,’ he told us, ‘and nothing is given to us.’ He always had his sayings. One of them was, ‘We help people without expecting to receive something in return. What matters is what you’re like inside — that is what God will see. So maybe we won’t be rich, but we will have peace inside us.'”

But now she feels less peace than before. “I don’t feel as comfortable now,” she said of the world beyond the workplace. “We live in a Latino community, and we bring our customs here, but we’re looked down on, judged, and criticized. People have the right to say we have to adapt to life here. It’s their country. We’re the foreigners. But I want us to be taken into account.”

Dominguez also made another type of sacrifice common to immigrant families —that of separation. Her oldest daughter is 24 and attending college in Mexico City, for which her mother sends back money every month, and she is unlikely to settle in the United States with the rest of her family. “You have to make a lot of sacrifices, and one of them is that some children will live here, and some will live there,” she said mournfully. “We won’t be together. You can’t have everything.”

Emeryville is still a beautiful city to Dominguez, but at the hotel, something has changed. “People in the office used to greet me,” she said. “Now they turn their backs, like we’re criminals.”

Just like her friend, Melquiades also learned survival skills from her father. After a lifetime as a construction worker, he recently came to live with her, and says he’s proud of her. “When I was a girl, he worked in factories in Mexico,” she remembered. “He was always fighting for the rights of the people around him, always getting fired for it.” His daughter’s predicament must sound familiar.

Now she feels insecure about whether she’s really found a home here. She said she wakes up in the middle of the night tormented by bills and problems. “I’m just living from one day to the next on what I make,” she said. “I don’t know what I’d do if I lost my job. Even though I’m back to work, I’m always worried about the next day. I’m just living with anxiety, all the time.”

Recognition of their labor is the yardstick of acceptance that both women fall back upon. “All we want is to work,” Melquiades pleaded. “We’re just fighting for the right to work.”