The official biography for singer Charles Bradley says he was discovered at age 51, when Daptone Records co-founder Gabriel Roth walked into the Tar-Heel Lounge in Bedford Stuyvesant, and saw Bradley performing with a James Brown tribute act under the stage name “Black Velvet.” Bradley’s producer, Tom Brenneck, has a slightly less romantic version of events: “The story I hear is that Charles actually showed up at Gabe’s door, and said ‘Hi, I’m a James Brown impersonator. Someone told me that I should meet you.”

That wouldn’t be too out of character for Bradley, who has a long history of wandering into clubs, singing a couple numbers, and hoping to get called back. Raised in Brooklyn and Gainesville, Florida, he spent twenty years working as a line cook in the Bay Area, built his vocal chops doing the Black Velvet act, and spent more time living the blues than singing about it. He left home at age fourteen, found work as a chef through Job Corps, and eventually formed a band — only to see his bandmates get drafted to serve in the Vietnam War. He spent decades moving from job to job and from project to project. He witnessed his brother’s murder at the hands of his nephew. Before Roth discovered him, he was living in an abandoned building. And now, at age 62, he’s released a soul album.

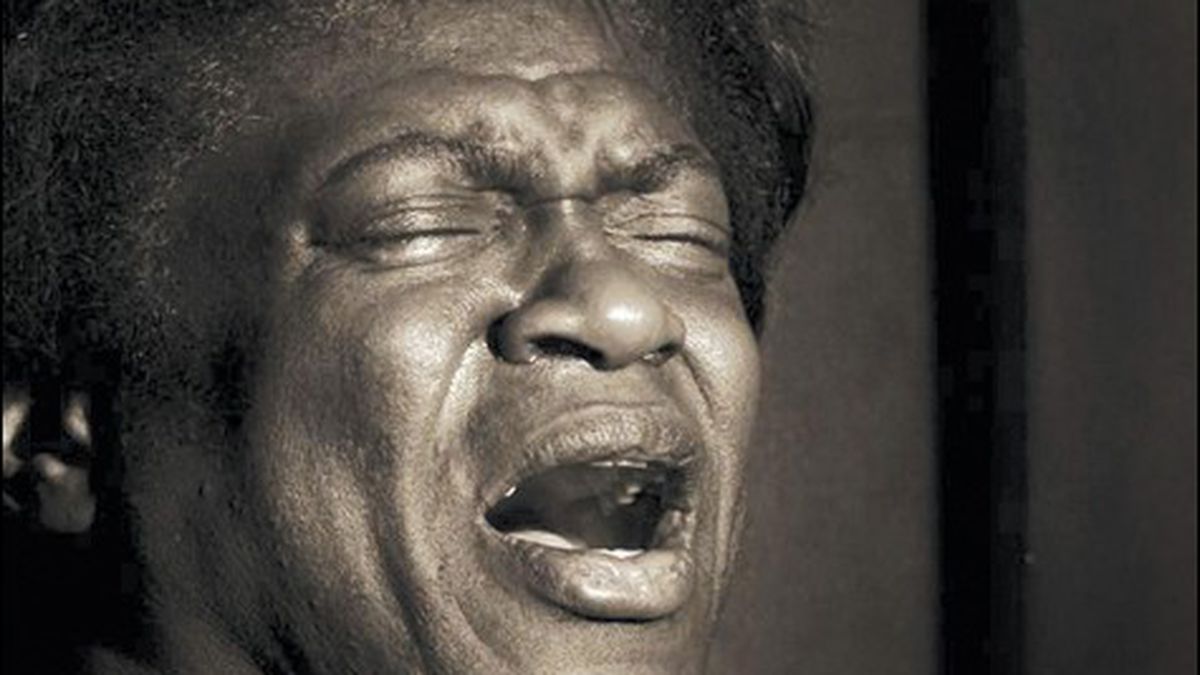

It’s one in a spate of so-called “revivalist” works to emerge under the Daptone imprimatur. But, as Brenneck assures, it’s no mere imitation. “He has this voice that sounds like a dinosaur, almost,” Brenneck said. “His voice sounds ancient, you know? Like when he closes his eyes and he’s about to sing, it’s just like, ‘Get ready. Here it comes.'”

Bradley, whose speaking voice is a low, crumbly growl, says he always loved singing. “My grandmother used to take me to the recreation center, and I used to watch the grown people dance,” he said. “I’d get on the floor and be dancing with these grown people …. Music made me feel — complete.” He became fully enamored of James Brown after catching the soul singer at Harlem’s Apollo Theater in the mid-Sixties. “They had the strobe light on both sides of the stage … and he came onstage like a fire,” Bradley recalled. “And I said, ‘I wanna do something like that.”

The fact that Bradley came up as an impersonator is one of the great ironies of his career. His admiration for James Brown is heartfelt and deep, and when he puts on the Black Velvet apparel, their resemblance can be uncanny — so says Bradley, at least. He still plays casinos up and down White Plains, as well as the B.B. King Blues Club & Grill on 42nd Street. But Bradley isn’t, by nature, the kind of artist who should be doing someone else’s act. His appeal lies not in being a showman, but rather in the integrity of his lyrics, and the grizzled soulfulness of his voice.

Evidently, it took Daptone a while to recognize that. “I don’t think they gave Bradley too much attention,” Brenneck said, reflecting on the singer’s first-ever recording with the Brooklyn-based label. “They just had him sing on a Sugarman Three song [for the band led by Roth’s business partner, Neal Sugarman]. They wrote the lyrics for him, and it was just kind of like, very kitschy, and very James Browny, and not very original. And it didn’t go anywhere.”

That was in 2001, roughly the same time as the record label’s genesis. Daptone would soon become one of the most ambitious indie soul labels in the country, with a roster that included The Budos Band and Sharon Jones & the Dap-Kings (which features Roth on bass and Brenneck on guitar). At that time, though, Brenneck was in another band called Dirt Rifle and Bullets. He had been sending demos to Daptone for a while. When Roth finally cottoned to Dirt Rifle, he sent Charles Bradley out to the group’s Staten Island studio for a rehearsal. It was the first time that Brenneck and Bradley met. “We ended up doing a couple singles for Daptone as Charles Bradley and the Bullets,” Brenneck said. “But those were kinda, like, not too hot. And they were also still stuck in that James Brown bubble.” He paused, reflecting. “At the time, I was only like 19 or 20, and I was just thrilled that this, you know, 50-year-old black man thought that the music we were making was soulful. That was just like, all of a sudden we felt credible to the kind of music we had been playing out in suburbia.”

Dirt Rifle ultimately morphed into The Budos Band, and Brenneck went on to start another project, The Menahan Street Band. “I thought that Charles’ voice would be a match made in heaven, because the music was much more mature than the stuff I was doing earlier. It wasn’t in the vein of James Brown, it was more in the vein of Joe Pecks, Otis Redding, or Percy Sledge. Traditional Sixties soul, but not James Brown.”

He called it. Bradley’s rumbly, impassioned baritone was, indeed, a perfect fit for the vintage soul of Menahan Street Band. The recording they made in Brenneck’s bedroom sounds exactly like a record made forty years ago, but better. Bradley wrote “Lovin’ You Baby,” a love ballad with a deeply sad undertow. All my life I’ve been searching for love/Mourning for love/Giving everything I know, he laments on the song’s first verse. He also wrote “Heartaches and Pain,” which touches on the story of his brother’s murder: I woke up this morning/My momma she was cryin’/So I looked out my window/Police lights was flashin’/People were screamin’/So I ran down to the street/A friend grabbed my shoulder/And said these words to me/’Life is full of sorrow. So I have to tell you this, your brother is gone.’

On the chorus, he breaks into a primal wail.

The resulting album, called No Time for Dreaming, initially came out on Brenneck’s label Dunham Records. Then he pitched it to Daptone, which released it earlier this year under Bradley’s name. It took about three years to produce, and in the interim, very little changed in the life of Charles Bradley. In private conversations, Bradley describes himself as “a humble person,” and says he’s well aware that people often mistake kindness for weakness. He illustrates points by quoting scripture. He still lives in the projects, in Bushwick, and serves as a caretaker for his mother. He gigs multiple times a week, both as Black Velvet and as himself. He says that one of his life goals is to bring the two personae “together in a unified way.”

If you ask Brenneck, though, there’s something uncannily personal about Charles Bradley that defies comparison to any other singer. “All the songs are stories about his life — and he’s been through hell,” the young producer said. “His voice, you know, I think it’s one of a kind.”

And it’s a relic. Musicians of Bradley’s generation are fading, and easily being supplanted by soul “revivalists” who approach the genre from both a celebratory and a scholarly angle. “There’s not too many peers of him that are just figuring out how to write songs, and get their careers underway — most of the guys are washed up,” Brenneck observed. “If anything, they’d try to rekindle a past career. But Charles, his past includes everything under the sun except singing for a living. He’s finally getting his break.”